In recent years, several innovative ENT physicians have been on the forefront of moving tympanostomy tube insertion for children out of the operating room and into the office setting. The chief benefits—avoiding the risks and inconveniences of general anesthesia, streamlining access to therapy, and easing the socioeconomic burdens on families—are well documented and acknowledged by most in the profession.

In recent years, several innovative ENT physicians have been on the forefront of moving tympanostomy tube insertion for children out of the operating room and into the office setting. The chief benefits—avoiding the risks and inconveniences of general anesthesia, streamlining access to therapy, and easing the socioeconomic burdens on families—are well documented and acknowledged by most in the profession.

Explore This Issue

April 2025But there’s less consensus on the best strategy for achieving that site-of-care switch.

On one side of the debate are surgeons such as Richard Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and past chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, N.Y. About 15 years ago, Dr. Rosenfeld started treating patients with recurrent otitis media and related middle ear conditions in his office using a manual surgical tube placement method. He couples traditional instruments and tubes from the OR setting with family/patient support methods he has been steadily refining over the years.

On the other side are a small but dedicated number of pediatric otolaryngologists who are championing a far more high-tech—and they say more feasible—approach: using automated systems such as Tula (Smith+Nephew) and the Hummingbird Tympanostomy Tube System (Preceptis Medical). These devices, approved in just the last few years, have been shown in some clinical trials to achieve near 100% success rates for in-office tube placement and 90th percentile scores in family caregiver satisfaction.

But here’s the catch: Neither approach has gained significant traction, with less than 10% of tympanostomies currently performed in ambulatory settings, according to a recent survey co-authored by Dr. Rosenfeld (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. doi: 10.1177/00034894211008063). Respondents to the survey, sent to members of the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology, cited several factors for their reticence, including difficulty with anesthesia of the eardrum, inability to keep the child from moving, and patients’ pain and emotional trauma.

For these and other otolaryngologists, many of those safety concerns center on the risks posed by general anesthesia, triggered in part by a 2017 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alert linking the procedure to neurodevelopmental dangers in children younger than three years of age (U.S. Food and Drug Administration. bit.ly/3PVQyNw).

“A strong case has been made that the risk is rare, but real,” Dr. Rosenfeld said. “I’m personally aware of a child who, [at] less than a year old, had tubes placed at a community hospital and ended up leaving a quadriplegic because of anesthetic complications. Now granted, that’s a one-off, but if you’re the family of that child, it’s not a one-off.”

Nathan Page, MD, a pediatric otolaryngologist and the medical director of the Phoenix Children’s Hospital’s Cochlear Implant Program, agreed that the 2017 FDA warning was the beginning of a sea change in how the medical community viewed the office-versus-OR tympanostomy debate.

“I remember being at a conference where Dr. Rosenfeld presented his technique of placing standard ear tubes with no sedation, and this was before the FDA alert was issued,” Dr. Page said. “Attendees started booing and shouting pretty negative terms like ‘unethical’ and even ‘torture.’ I mean, they were ready to grab pitchforks.” After the FDA alert, however, “the conversation really started to change,” he said. “Pediatricians did not want to refer their kids to me for tympanostomies because they said they were concerned about the risks posed by general anesthesia.”

And it wasn’t just clinicians, he noted. “I also had parents asking whether this could be done in an office setting.”

For otolaryngologists who were not comfortable replicating Dr. Rosenfeld’s technique, however, there was no viable office-based alternative—until, that is, the FDA began approving the automated systems and early adopters began using them.

Dr. Page is one of those early adopters. “My first thought when I started hearing about these automated systems was, well, we do all sorts of in-office procedures in young children without any sedation, whether it be foreign body removal, nasal cautery, etc. And we’ve always done tubes in the office for adults and teens who can hold still.” The big change with the automated devices, he noted, “was that I can now apply this to a one-year-old or a two-year-old. So, this seemed like a natural progression—and frankly a pretty big deal.”

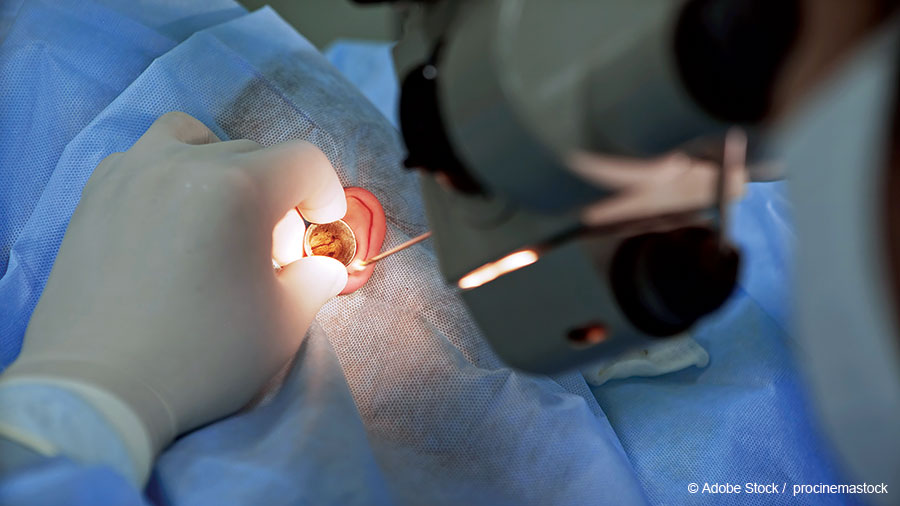

Dr. Page and his team opted for the Hummingbird system, which gained an expanded FDA approval in 2022 for use in all children six months and older. Unlike conventional tympanostomy tube insertion, which requires several surgical instruments and multiple passes into the ear for tube placement, Hummingbird automatically makes a single incision and delivers a preloaded tube in a single pass, according to the manufacturer.

Leave a Reply