SAN DIEGO—Eben Rosenthal, MD, medical director of the Stanford Cancer Center, described a case involving a lesion in the oral cavity. It was resected, but there was a surprise: a separate lesion, with a focus of less than 3 mm of tumor. The lesion was discovered only because the Stanford surgeons were using a fluorescent tag attached to an anti-epithelial growth factor antibody that homes in on tumors. The fluorescent dye lit up the satellite lesion, which, after testing, was found to be pathologically positive for tumor.

Explore This Issue

March 2020“We wouldn’t have even known to look for it,” he said.

The use of fluorescent light to see through normal tissues down to head and neck tumors is showing promise as a way of guiding surgeons and improving margins and outcomes—and occasionally discovering other tumors that weren’t even anticipated, Dr. Rosenthal said here during a panel discussion at the Triological Combined Sections Meeting.

How It Works

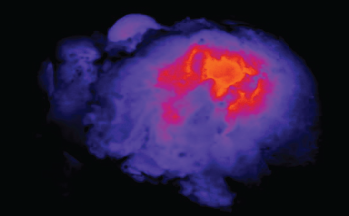

Detection of tumor close to the surgical margin on resected specimens is a key advantage of fluorescent light technology, Dr. Rosenthal said. The approach is based on the passage of light through normal tissue. The tumor glows bright from the contrast media. The intensity of light that can be seen shining through depends on the depth of the normal tissue on the deep surface of the surgical specimen.

“The deeper the tumor is from the cut surface of the specimen, you see less fluorescent light,” he said.

The approach doesn’t provide exact distances and depths of the tumor, but in a trial of more than 20 patients, researchers found a high correlation between fluorescence intensity and tumor location, with sensitivities and specificities greater than 89% (Cancer Res. 2018;78:5144-5154). The main goal is to find the “sentinel margin,” or margins, the area of the specimen where the tumor is closest to the cut surface (the smallest margin) and, therefore, most likely to be a close or positive margin. Then surgeons assess the depth of that one area of the specimen on frozen section to ensure the margins are clear, he said.

“You can translate that to where you’re going to sample, where you’re going to take your frozen section,” Dr. Rosenthal said.

Reducing Positive Margins

The field could use new ways to reduce the rate of positive margins, which has been flat over the past 20 years. Dr. Rosenthal noted that this is particularly true for oral cavity cancer, which has one of the higher overall positive-margin rates, according to data from the National Cancer Database. Many labs are working on perfecting the technology, but it is still several years from approval, he said.

“The impact of this technology is very high,” Dr. Rosenthal said. “It’s going to be probably another five years before these agents are commercially available—but hopefully sooner.”

It’s going to be probably another five years before these agents are commercially available—but hopefully sooner. —Eben Rosenthal, MD

Quyen Nguyen, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at the University of California, San Diego, said that with so many cancer patients needing surgery, and positive margins remaining common, it’s encouraging that research on ways to better visualize head and neck tumors and surrounding structures is intensifying.

“Positive surgical margin is treatment failure,” she said. “We are all so fortunate to be working as clinical surgeons at this moment in time.”

Research Underway

Image of light shining through a tumor specimen.

© Eben Rosenthal, MD

Dr. Nguyen described two products for which she is a co-inventor. One is a ratiometric activatable cell-penetrating peptide, a way of imaging a cancer tumor in real time, with colors indicating the level of proteases associated with the tumor (Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3167-3173).

“This is an activity-based model,” she said. “This is not just how close you are to the margin—this is also how much cancer you have.” A phase 2 study on this agent, AVB-620, is being developed by Avelas Biosciences and is expected to be finished this year. Dr. Nguyen is a scientific advisor for Avelas.

In another project, Dr. Nguyen and other researchers are working to perfect a way to illuminate nerves in the surgical field. Estimates on nerve injuries in head and neck cases vary widely but have been found in up to 25% (Ann Surg. 2019;270:69-76). The numbers are even higher in other types of cancer, Dr. Nguyen said.

The product, a 17-amino-acid chain, has the ability to light up not only the main branches of a nerve, but also its smaller branches that extend deeper into the tissue. A side-by-side view in an animal model with and without the use of the fluorescent agent known as ALM-488 showed a striking difference in how well the nerves could be seen. Dr. Nguyen is co-founder and CEO of Alume Biosciences, which is developing ALM-488.

“In the next five years, I think we’re going to see fluorescence guidance enabling precision surgery with tumor margins really well delineated for the surgeon, intraoperatively and in real time, and the nerve being delineated—not just what’s already exposed but what’s underneath the surface,” Dr. Nguyen said.

Ultrasound-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation

David Steward, MD, director of head and neck surgery at the University of Cincinnati, said that ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA), using ultrasound images to visualize and kill tumors with radio waves, may be applicable to many types of thyroid nodules. A systematic review published last year found that RFA, laser ablation, microwave ablation, and high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation performed similarly for solid benign nodules, with a volume reduction of 50% to 75% after six to 12 months, with improvement over time. The rate of reduction tended to be greater for nodules less than 3 cm, Dr. Steward said (Thyroid [published online ahead of print December 4, 2019]. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0707).

For hyper-functioning nodules, a recent pooled estimate found that RFA resolved hyperthyroidism 57% of the time at six to 18 months, with a volume reduction of 79% after a year (Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2019;20(1)37-44).

For nodules for which surgical resection is considered, Dr. Steward said that surgery tends to be more effective at reducing certain symptoms, such as trouble swallowing and shortness of breath. On the other hand, he said, RFA tends to lead to far greater satisfaction from patients. A review of more than 1,400 RFA cases from several years ago found a complication rate of just 3.3%, demonstrating that while the complication rate is low, it’s not nonexistent (Radiology. 2012;262:335-342).

“Surgery is more effective, but it might be more effective than it really needs to be—causing a little bit more pain and discomfort post-operatively,” Dr. Steward said.

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.