The level of technical complexity and the stakes involved for patients make correcting facial trauma one of the most difficult tasks for head and neck surgeons. During the session “Management of Soft Tissue and Bony Facial Trauma,” a panel of experts brought their know-how and experience to the table. Here are some of their main points.

Zygomatic Bone

Stephen Park, MD, director of the division of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, said fixing complex (or “tripod”) fractures to the zygomatic bone is one of the most challenging repairs to get exactly right. “Once it is fractured and displaced, the reduction is not in a linear vector,” he said. “We’re not just popping the bone out in a single dimension. You usually have to move it up and out and then rotate it to get it precisely back in position and restore facial symmetry.”

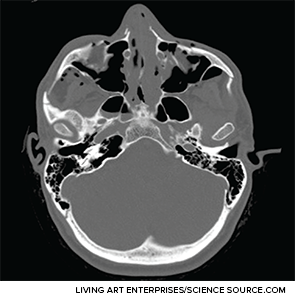

Axial CT image depicting extensive facial fractures.

To get the zygomic bone three-dimensionally and anatomically correct, he said, sometimes it is necessary to expose the zygomatic arch, the zygomatic-sphenoid fracture line, or both. The arch is the only buttress that otolaryngologists can align that sets the anterior-posterior vector, he added. Also, he said, “The zygomatic-sphenoid fracture is the only fracture that courses through all three dimensions in space, and it is your guide in complex cases.”

Craniofacial Reconstruction

Kris Moe, MD, professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle, offered three main concepts to improve outcomes in these cases.

First, he said, operate if there’s an alteration in form in function. In many cases, even with severely broken bones, this is not the case, and these considerations must be weighed by the patient. “The patient makes the decision,” Dr. Moe said.

Second, using endoscopy improves the lighting and the magnification and allows for smaller incisions and less retraction. “These things add up to more precision, less morbidity, and better outcomes,” he said.

From the audience

It was an especially good talk on dealing with high-impact injuries to facial structures in the war. Since you don’t see it commonly, it’s actually nice to hear about it from someone [who sees these injuries much more frequently].

—Jay Bhatt, MD, otolaryngology resident, University of California, Irvine

Finally, he added, virtual reconstruction using computers can be very helpful in cases in which landmarks are destroyed and a surgeon can’t see the entire fracture site. A mirror image of the other side placed digitally over the injured side provides landmarks that wouldn’t otherwise be available. A case series at his institution found that this approach improved outcomes and reduced the need for revision surgery.

High Impact Injuries in a Combat Setting

Col. Joseph Brennan, MD, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, discussed the lessons he learned reconstructing faces mangled by explosives and ripped apart by gunfire.

On soft tissue reconstruction, he said, key steps include extensive irrigation, maintaining any tissue that has any chance of still being viable, and closing the face immediately. “Most important, you need to avoid the home run surgery,” he said. “Early in the war, we tried to reconstruct these people in one setting. And it doesn’t work.”

For mandible fractures, he again stressed “occlusion, occlusion, occlusion.” He also said he considers arch bars the gold standard in treatment and stressed the importance of preserving soft-tissue attachments and all bony fragments and using three-dimensional computed tomography for planning.

For midface fractures, again he stressed occlusion and suggested rebuilding from the stable to the unstable points toward the malar eminence. The malar eminence, he said, is the key, since it’s the most prominent projection in the midface.

Secondary Reconstruction

In cases of secondary traumatic facial soft tissue deformities, it’s important not to let worries about scarring override placement considerations, said William Shockley, MD, chief of the division of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill. “The facial and nasal contours are more important than facial scars,” he said. “And the position and orientation of these special facial structures are more important than facial scars.”

The tissues adjacent to the injury contract, causing a pull on the structure, so it’s critical to release or remove the scar that is causing the deformity to get the facial structure back to where it belongs. Once it’s back to its original position, the new defect must be reconstructed with a local flap or full thickness skin graft, for instance. “Don’t allow the secondary defect to deter you from repositioning the facial structure,” he said.

Arch Bars

Robert Kellman, MD, professor and chair of otolaryngology and communication sciences at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, questioned the value of using arch bars in mandibular fractures. He cited studies that concluded that there were no clear differences in outcomes whether or not arch bars were used.

At his institution, arch bars have been used less and less frequently in recent years in cases of non-subcondylar fractures. In 2013, he and his colleagues compared results and found no significant difference in complication rates in cases with arch bars compared to those without. In cases of a single angle fracture, there was no significant difference in the frequency of malocclusion. There was a significant difference, however, in cases with a single angle fracture and a non-angle fracture, with malocclusion in 2.5% of cases in which arch bars were used and in 19% of cases in which they were not.

“I’m not sure that I’m totally comfortable recommending that we drop the arch bars in the majority of cases,” Dr. Kellman said. But, he added, “Certainly everyone agrees that in multiple fractures, combinative fractures, complex fractures, [and] associated midfacial fractures, we really have very few options and we must do it.”