Separating the responders from the non-responders when it comes to surgery for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a goal for all surgeons in this area, and a group of experts, focusing mostly on the role of the tongue in OSA, tackled the topic during a panel session.

Explore This Issue

March 2015“There is a variable response to UPPP [uvulopalatopharyngoplasty] and it’s important to determine what subgroup of the sleep apnea patients would benefit from surgery,” said Kathleen Yaremchuk, MD, MSA, chair of the department of otolaryngology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit. The literature suggests that success rates with UPPP might be 50% or less over the long term.

Eric Kezirian, MD, MPH, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, emphasized that advancements in evaluation techniques have shown that the tongue can play a major role in OSA but that other structures may contribute to airway obstruction.

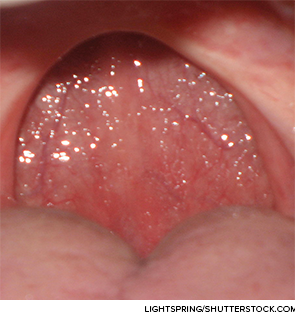

Techniques such as Friedman staging—which defines categories based on the size of the tongue and the size of the tonsils—can be useful as a first step because “it is associated with outcomes after UPPP with tonsillectomy,” he said. Those with large tonsils but relatively small tongues tend to do well, but those with large tongues tend to experience worse outcomes.

Drug-induced sleep endoscopy is another OSA evaluation technique that is based on fiberoptic examination of the airway under sedation. Dr. Kezirian’s research has shown the importance of the palate, oropharyngeal lateral walls, tongue, and epiglottis. One study of 33 patients who experienced persistent OSA after palate surgery showed that “almost all of them had obstruction related to the tongue, but that the other structures also contributed in many patients.”

From the audience

We’ve all had those patients who are not improving with our upper airway surgical techniques. And I’ve done base of tongue surgery and palatal surgery, and so I think [Inspire] is going to be one more treatment option for those who aren’t responders.

—Doug Anderson, MD, Ogden Clinic, Utah

Ho-Sheng Lin, MD, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Wayne State University in Detroit, said that airway obstruction can be multi-layered and that this can sometimes be missed. “A failure to recognize the multi-level nature of airway obstruction may account for the poor surgical outcomes following UPPP,” he said.

Precise location of the blockage involved in the OSA is crucial to the surgical approach, he added. “It’s extremely important that we know exactly where the blockage is in the upper airway,” he said.

“Whether it be anterior-posterior, lateral obstruction, or concentric collapse, you need to use different techniques to address those problems.”

At his center, Dr. Lin and his colleagues recently analyzed data to see why some patients respond to surgery and some don’t. They identified three factors: the well-known predictor of body-mass index, the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), and the presence of lateral velopharyngeal collapse.

The latest approach—transoral robotic surgery (TORS)-assisted partial glossectomy—has been found to have response rates of approximately 50% to 60%, he said.

Upper Airway Stimulation

M. Boyd Gillespie, MD, professor and director of the Medical University of South Carolina Snoring Clinic in Charleston, talked about the emergence of the upper airway stimulation system, Inspire (Inspire Medical Systems, Maple Grove, Minn.), which received FDA approval in April 2014.

The device is an implantable nerve stimulator that’s similar to a pacemaker, indicated for patients with moderate to severe OSA (AHI of 20 or higher but not greater than 65) who failed or couldn’t tolerate positive airway pressure treatment. “Patients with OSA have reduced neural tone,” said Dr. Gillespie, who has worked as a consultant for the manufacturer. “So it may not be all due to fat in the tongue. Some of it may be due to reduced neural tone. … What we’re trying to do with upper airway stimulation is to account for that loss of neural tone by providing more neural impulse to these glossal groups that perform the dilator function.”

In findings published last year, the system led to a 68% reduction in AHI and a 70% reduction in oxygen desaturation index (ODI) (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:139-149). Those with a complete concentric collapse of the airway were excluded because preliminary studies found that they didn’t respond to the treatment.

Glossoptosis

Stacey Ishman, MD, MPH, surgical director for the Upper Airway Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed treatments for glossoptosis.

She reviewed recommendations from the European Respiratory Society Task Force on non-CPAP therapies in sleep apnea. Task force members cautioned that multi-level surgery is not recommended as a substitute for CPAP, only as a salvage procedure after CPAP and other more conservative approaches have failed, since success of such surgery is often unpredictable and less effective than CPAP.

Recommendations also included considering the lingual tonsils early and considering a hyoid myotomy and suspension with a retroverted epiglottis.

Additionally, Dr. Ishman said that sliding genioplasty is an option for retrognathic patients, and posterior midline glossectomy often can be done with a hyoid procedure to decrease tissue and open up the posterior airway space. “The airway evaluation is really critical in determining what to do for these cases,” Dr. Ishman said. “Sleep endoscopy can be very useful, and a view of the true vocal cords can really help you determine narrowing of the retroglottis.”