For otolaryngologists seeing increasing numbers of children with sleep-disordered breathing, whether or not to refer children for a polysomnography (PSG) prior to surgery is not a decision easily made. Currently, only about 10 percent of otolaryngologists request a sleep study in children with sleep-disordered breathing prior to surgery (Laryngoscope 2006;116(6):956-958).

Although limited resources and lack of access to overnight sleep centers are well-known practical limitations to widespread use of sleep studies, otolaryngologist also need to better understand when sleep studies are necessary.

This need is highlighted by data estimating that sleep-disordered breathing accounts for most of the estimated 530,000-plus tonsillectomies performed each year in the U.S. for children under 15 years of age (Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;11:1-25), along with the perception by some that a good many of these may be unnecessary surgeries that could have been avoided with more accurate diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing conditions.

"The average success rate of a physician to accurately diagnose a sleep-disordered breathing using clinical skills alone is between 60 to 65 percent, which means that 30 percent of children sent to surgery do not need surgery," said David Gozal, MD, a pediatric sleep specialist at the University of Chicago Medical Center. "That is a wrong way to approach medicine, especially since you don’t know if the disease is present or whether the risk-benefit of doing surgery is justified."

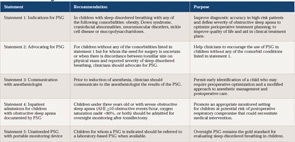

To help otolaryngologists determine the best use of PSG when faced with a child who has sleep-disordered breathing and is being considered for tonsillectomy, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) recently published practice guidelines.

As with previous AAO-HNS guidelines, these were developed by a committee composed of experts from the numerous specialties that manage children with sleep-disordered breathing, including anesthesiology, pulmonology, otolaryngology, pediatrics and sleep medicine, and are meant only to guide clinical practice, not to replace clinical judgment.

Although the recommendations were made by this multispecialty committee, the guidelines specifically target otolaryngologists and are not meant to be comprehensive for all practitioners who care for children with sleep problems, said coauthor Ron Mitchell, MD, who is also professor and chief of pediatric otolaryngology at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Children’s Medical Center in Dallas.

Best Use of Limited Resources

The guidelines are driven in part by the need to help otolaryngologists make the best use of limited resources, Dr. Mitchell said. "We know that there are not enough resources to provide a sleep study for every child prior to tonsillectomy," he said. "We are not saying that every child with a sleep problem who is due to undergo a tonsillectomy should have polysomnography, but that there are certain categories of children for which [PSG] is extremely helpful."

Of the five recommendations in the guidelines, the first two emphasize what the AAO-HNS consider the best indications for referring a child for a sleep study prior to surgery. These include children with sleep-disordered breathing who also have select comorbidities that place them at higher risk of perioperative complications.

These recommendations highlight a subpopulation of children in whom the committee felt that sleep studies are currently underutilized, according to another coauthor of the guidelines, Norman Friedman, MD, director of the Children’s Sleep Medicine Laboratory at the University of Colorado in Aurora, Colo.

Although supportive of these recommendations and the attempt by otolaryngologists to properly utilize sleep studies, Dr. Gozal emphasized that, under these guidelines, too many children will still receive suboptimal diagnosis and undergo unnecessary surgery. He said another challenge is determining the success of a surgery if the reason for the surgery is not sufficiently defined or known. Published evidence suggests that the overall cure rate of adenotonsillectomy for sleep apnea in children is much lower than previously anticipated (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;138:265-273), he said.

But according to Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, medical director of the St. Joseph Sleep Wellness Center in Lexington, Ky., and an ENT Today editorial board member, the definition of sleep-disordered breathing in children is evolving. "It is not clear, based upon current research, that polysomnography identifies all children who have sleep-disordered breathing and will benefit from surgery," she said. "Children with snoring, and a negative standard PSG have an increased incidence of neurocognitive dysfunction and some derive benefit from adenotonsillectomy. The inclusion of nasal pressure monitoring in children, which became standard in 2007, has improved but not resolved this issue."

For Dr. Gozal, the 2002 guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) remain the most reliable (Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):704-12). These guidelines recommend a preoperative PSG for all children with symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. According to Dr. Gozal, a member of the committee that is currently updating these guidelines, the upcoming updated AAP guidelines will recommend more frequent use of sleep studies based on evidence published over the past 10 years.

Are Guidelines Insufficient?

Sally R. Shott, MD, pediatric otolaryngologist, professor of otolaryngology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Cincinnati, Ohio, and a member of the Executive Committee of the Section on Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery of the AAP, said both the AAO-HNS guidelines and the 2002 AAP guidelines correctly identify the inadequacies of clinical examination alone in differentiating between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and sleep-disordered breathing from primary snoring. She disagrees with both sets of guidelines as to who should be referred for a sleep study, however. Voicing her own personal opinion, and not that of the committee, she said that she does not think a preoperative sleep study is needed "if a child, even if in the high-risk groups, has symptoms of obstruction and sleep-disordered breathing and an exam matches that history."

She criticized the AAO-HNS guidelines for lacking a recommendation for a postoperative sleep study in selected patients, however. "I was disappointed that the AAO-HNS guidelines did not address this, as there are published studies on several of the ‘at risk’ groups showing that while a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A) helps with obstructive sleep apnea, it doesn’t always totally cure the OSA, especially in the children in the ‘at risk’ groups," she said.

These children, she said, can forego a preoperative sleep study if they have symptoms of obstruction and sleep-disordered breathing that are confirmed by physical exam. A postoperative sleep study is more important than a preoperative sleep study to confirm to that the obstruction has been fully treated by a T&A, she said.

According to Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, professor and chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., and chair of the AAO-HNS Guideline Development Task Force, the issues surrounding the postoperative use of PSG were outside the scope of the current guidelines and were addressed in the previously published 2011 guidelines on tonsillectomy (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1 Suppl):S1-S30). Dr. Rosenfeld also pointed out that the current guidelines do emphasize that persistent sleep-disordered breathing or OSA are more common in high-risk children compared to healthy children and that the emphasis is therefore on obtaining a baseline PSG prior to surgery in high-risk children.

Dr. Shott also said the recommendation made in statement four of the AAO-HNS guidelines for postoperative observation should include more at-risk patients than those currently listed. To the current list, which includes children under three years or those with OSA and may include those with certain co-morbidities (i.e., obesity, neuromuscular or craniofacial disorders, Down syndrome, mucopolysaccharidoses and sickle cell disease), Dr. Shott would add other conditions that the AAP guidelines identified as high risk, including cardiac complications of OSA, failure to thrive, prematurity and recent respiratory infections. "The AAO-HNS guidelines discuss studies that show that it can take up to 18 hours for post operative respiratory complications to occur, and that means that respiratory complications could occur in ‘at risk’ children after they were sent home," she said.

In response to this suggestion, Dr. Rosenfeld emphasized that the comorbid conditions included in the AAO-HNS guidelines that may warrant postoperative observation are those with well-documented evidence of increased OSA severity. In addition, he said that because a PSG is recommended for all of these at-risk children, any with severe sleep apnea would be identified before surgery and admitted for observation. He acknowledged, however, that overnight observation for other children may be appropriate. "There is nothing in the document that prohibits a clinician from admitting a child with any of these conditions, and, clearly, when there are other comorbidities, such as cardiopulmonary disease, admission would be appropriate even if the [PSG} results were non-severe," he said.

Despite these differences, Dr. Shott said the inherent benefit of a guideline is to present a consensus opinion on a subject that not everyone will agree with. "All of us practice somewhat differently and probably disagree with each other on various specific points within the guideline," she said, adding that a guideline "should take a middle-of-the road approach to reflect disparity of support services nationwide while promoting patient safety and quality of care."

Joseph Kerschner, MD, professor of otolaryngology and communication science at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wis., who generally agrees with the guidelines, said they weren’t written to address the bulk of children who are seen outside of major children’s hospitals and academic health centers. "Most sleep-disordered breathing is managed outside of these centers, and these guidelines really address the most complex children with sleep issues and weren’t written to address the average child suspected of sleep-disordered breathing," he said.

He added that he does not expect the guidelines to have a large impact on the broader population of children who undergo surgery for sleep-disordered breathing.

Dr. Kerschner emphasized that children with complex problems who are defined as high risk require a high level of expertise from both the surgeon and the entire team to mitigate the potential for complications that may arise during a tonsillectomy. "These operations are not to be taken lightly," he said.

Portable Monitoring Devices

Among the gaps in research identified in the guidelines is the use of portable monitoring devices to provide some objective data when an overnight PSG is not feasible. The guidelines make clear that a PSG remains the gold standard and should be used when indicated.

"What we are saying in the guidelines is that the evidence supports the use of full-night, lab-based sleep studies, and there is not enough evidence to say yes or no to monitoring," Dr. Mitchell said. He emphasized that more research is needed to identify the role of portable monitoring, which, he said, could have an important and extensive future role. ENT TODAY

Leave a Reply