What if the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1, the test developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), for which every medical student has studied diligently since the 1990s, was no longer released with a numeric score, but rather taken as pass/fail?

The journal Academic Medicine recently published an invited commentary in which six medical students from across the country suggested just that (Acad Med. 2019;94:302–304). Their article was published along with a response from Peter Katsufrakis, MD, MBA, president and CEO of the NBME, and Humayun Chaudhry, DO, MS, president and CEO of the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) (Acad Med. 2019;94:305–308).

The student commentary described a negative academic climate to which they said the exam was contributing, a climate increasingly addled with competition and anxiety over matching into competitive subspecialties, as well as a stigma for those choosing to specialize in less competitive areas, such as primary care (the assumption being that they didn’t score high enough on Step 1 to have better choices).

“For many students, participation in the Step 1 climate is a profoundly negative experience,” the commentary said. “In our view, the Step 1 climate contributes to the ongoing mental health crisis affecting the medical community, characterized by increased rates of anxiety, depression, burnout, and suicide among physicians and physicians in training.”

I spent six weeks [studying] for Step 1 solely. I went and stayed with family in the country and lived and breathed Step 1 for the entire time. —David Lee, MD

Anand Devaiah, MD, an associate professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Boston University School of Medicine and president of the Society of University Otolaryngologists, thought the medical students’ commentary was thoughtful and a “well-reasoned treatise” that brought up excellent points on the merits and disadvantages of moving to a pass/fail system.

David Lee, MD, a fourth-year otolaryngology resident at University of Cincinnati Medical School in Ohio, felt the pressure to do as well as possible on Step 1. “I really don’t think I can speak for anyone else,” he said, “but if an applicant knows they want to do otolaryngology, then knowing it is one of the most competitive specialties and the Step 1 score is one of the most consistent factors that residencies use, the otolaryngology residency applicant needs do what they feel necessary to match.”

© DDekk / shutterstock.com

tacey T. Gray, MD, program director of the otolaryngology residency program at Harvard, said the issues at hand highlight the fact that there should be a more in-depth conversation between students and the people who are in the position of creating assessment examinations so that students better understand what is being assessed and why it is important to the field of medicine. “I think if students better understood how scores were being used to assess their application for residency, there would be less anxiety about the match process. As educators, being open to a conversation with our students about their concerns is crucial, as they represent the future of this specialty and will ultimately be the educators in the next generation,” she said.

While many physicians a generation ago prepared for Step 1 on their own in just a couple of weeks while also attending medical school classes, students today are taking a different route, some even taking time off from their med school classes entirely. “I spent six weeks [studying] for Step 1 solely,” said. Dr. Lee. “I went and stayed with family in the country and lived and breathed Step 1 for the entire time.”

A test prep cottage industry has formed around Step 1, as many consider it a key indicator of a medical student’s preclinical medical education and very important to matching into the student’s top choice residency program. Dr. Lee said that, for him, taking a test prep course was necessary. “The course I chose kept me structured and regimented in my review of the enormous [amount of] study material, and I needed that,” he said. “Not everyone may feel the same, but the fear of a subjectively bad Step 1 score is real and may drive those who wouldn’t need it to break down and make the purchase.”

Cost and Diversity

According to the medical student commentary, “The Step 1 climate is a barrier to diversity and inclusion in medicine and contributes to a destructive culture of hierarchy among specialties.” The commentary cites a study that noted lower Step 1 scores in underrepresented minorities, women, and students whose parental income was less than average, as well as a study that showed African American medical students were less likely to receive invitations to interview based on their Step 1 score, saying, “… the emphasis on Step 1 is a barrier to the creation of a diverse physician workforce comprising individuals that come from different cultures, speak different languages, and represent the patients they care for” (Acad Med. 1995;70:1142–1144 and 2001;76:1253–1256).

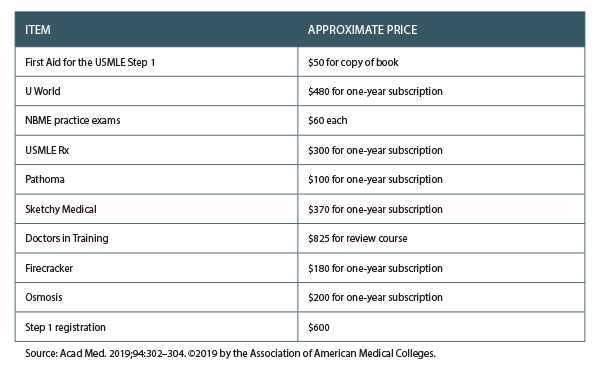

This brings up whether the cost of roughly $1,000 for test prep materials (and potentially thousands more for students wealthy enough to hire private tutors) is discriminatory toward those who will have to take out yet another loan to afford it. “Medical students are graduating with up to $300,000 in debt, so in that context, $1,000 is a small additional investment,” said Cristina Cabrera-Muffly, MD, associate professor and residency program director in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. “That being said, if most students are taking a prep course, this should be included in the medical school curriculum. (See “Approximate Prices of USMLE Step 1 Exam Preparations Commonly Used by Students, below.”)

Table 1. Approximate Prices of USMLE Step 1 Exam Preparations Commonly Used by Students

Test Important to Directors

Is the test as important to residency program directors as students think it is? The answer is complex, and opinions vary from director to director and school to school. But with 400 medical students often applying for four otolaryngology residencies, the scored test still matters a great deal to some program directors. “Going to pass/fail would make it harder to screen applicants and would increase the pressure for applicants to publish research and do more volunteer activities,” said Dr. Cabrera-Muffly, MD.

Dr. Devaiah said that, personally, he likes receiving an applicant’s USMLE numeric score. It does give some useful information about the individual, but he acknowledges that scores can be overemphasized by programs when reviewing applications. “I think of the scores as more of a threshold, where scoring at or above a certain level is enough to satisfy this requirement in an applicant’s application. To me, that’s a reasonable way to use this information. Scoring higher than the threshold is unlikely to confer an additional advantage in predicting success in residency,” he said. He added that the idea of using thresholds in scoring would philosophically support pass/fail scoring, but he feels some additional stratification into quartiles or other divisions might be more helpful to programs and applicants alike.

Barry Schaitkin, MD, director of the otolaryngology residency program at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said that USMLE Step 1 is something that helps his review committee compare students from different medical schools. “A good score allows for the student who is not at an elite medical school, but did very well there, to get noticed,” he said. “On the other hand, when we look at a medical school that has awarded for a surgery clerkship, 60% honors and 40% high pass and no pass and no failure, it seems that schools have made grades an even worse metric. Practically no one applies to go into otolaryngology who didn’t get honors for the clerkship, so it also does not provide a hard piece of data from the program that knows the applicant best.” (As president of the Otolaryngology Program Directors Organization (OPDO), Dr. Schaitkin says there is no consensus on this issue among OPDO members at this time, and he can’t comment on behalf of the organization.)

Some Skills Difficult to Test For

Communications skills, empathy, and professionalism, all factors that go into making a knowledgeable medical student into a superb physician, are difficult to assess on a standardized test. With the move to pass/fail grading for the first two years at some of the nation’s most elite medical schools (Harvard, Yale, and Stanford among them), it can also be difficult to know how medical students have performed in their classes, which may be another strike against assessing medical knowledge. Graded classes, however, still exist at the majority of medical schools.

“As otolaryngologists, we deal with conditions that affect a patient’s quality of life and how patients communicate with the world,” Dr. Gray said. “Being able to connect with patients and providing empathic care is extremely important. I think most programs are really interested in selecting candidates who will not only be gifted clinicians, but will also be compassionate and caring physicians. If there was an objective metric to measure that potential, we would utilize it in the selection process. Currently, we don’t have a metric to reflect that. Hopefully we will in the future.”

Renée Bacher is a freelance medical writer based in Louisiana.