Cost and Diversity

According to the medical student commentary, “The Step 1 climate is a barrier to diversity and inclusion in medicine and contributes to a destructive culture of hierarchy among specialties.” The commentary cites a study that noted lower Step 1 scores in underrepresented minorities, women, and students whose parental income was less than average, as well as a study that showed African American medical students were less likely to receive invitations to interview based on their Step 1 score, saying, “… the emphasis on Step 1 is a barrier to the creation of a diverse physician workforce comprising individuals that come from different cultures, speak different languages, and represent the patients they care for” (Acad Med. 1995;70:1142–1144 and 2001;76:1253–1256).

Explore This Issue

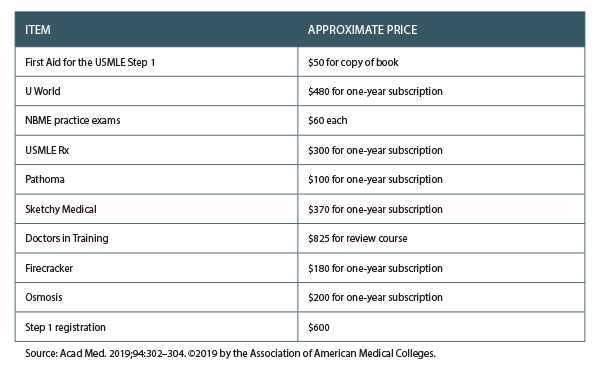

April 2019This brings up whether the cost of roughly $1,000 for test prep materials (and potentially thousands more for students wealthy enough to hire private tutors) is discriminatory toward those who will have to take out yet another loan to afford it. “Medical students are graduating with up to $300,000 in debt, so in that context, $1,000 is a small additional investment,” said Cristina Cabrera-Muffly, MD, associate professor and residency program director in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. “That being said, if most students are taking a prep course, this should be included in the medical school curriculum. (See “Approximate Prices of USMLE Step 1 Exam Preparations Commonly Used by Students, below.”)

Table 1. Approximate Prices of USMLE Step 1 Exam Preparations Commonly Used by Students

Test Important to Directors

Is the test as important to residency program directors as students think it is? The answer is complex, and opinions vary from director to director and school to school. But with 400 medical students often applying for four otolaryngology residencies, the scored test still matters a great deal to some program directors. “Going to pass/fail would make it harder to screen applicants and would increase the pressure for applicants to publish research and do more volunteer activities,” said Dr. Cabrera-Muffly, MD.

Dr. Devaiah said that, personally, he likes receiving an applicant’s USMLE numeric score. It does give some useful information about the individual, but he acknowledges that scores can be overemphasized by programs when reviewing applications. “I think of the scores as more of a threshold, where scoring at or above a certain level is enough to satisfy this requirement in an applicant’s application. To me, that’s a reasonable way to use this information. Scoring higher than the threshold is unlikely to confer an additional advantage in predicting success in residency,” he said. He added that the idea of using thresholds in scoring would philosophically support pass/fail scoring, but he feels some additional stratification into quartiles or other divisions might be more helpful to programs and applicants alike.

Barry Schaitkin, MD, director of the otolaryngology residency program at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said that USMLE Step 1 is something that helps his review committee compare students from different medical schools. “A good score allows for the student who is not at an elite medical school, but did very well there, to get noticed,” he said. “On the other hand, when we look at a medical school that has awarded for a surgery clerkship, 60% honors and 40% high pass and no pass and no failure, it seems that schools have made grades an even worse metric. Practically no one applies to go into otolaryngology who didn’t get honors for the clerkship, so it also does not provide a hard piece of data from the program that knows the applicant best.” (As president of the Otolaryngology Program Directors Organization (OPDO), Dr. Schaitkin says there is no consensus on this issue among OPDO members at this time, and he can’t comment on behalf of the organization.)