Using robotic arms, surgeons can now remove the thyroid gland through an incision in the axilla, or armpit, thereby avoiding the large scar on the front of the neck caused by traditional thyroid surgery. The procedure offers no other benefits over the traditional approach developed a century ago by Emil Theodor Kocher, MD, according to head and neck surgeons who perform the robotic surgery. In fact, it takes longer to recover from the robotic surgery, they say, with some patients complaining of chest numbness for months afterwards.

So why is this procedure, which has been performed about 125 times in the U.S., according to the small group of surgeons who have embraced it, and approximately 1,500 to 2,000 times worldwide, gaining in popularity? Head and neck surgeons interviewed by ENT Today touted the procedure’s precision and application to other head and neck operations.

F. Christopher Holsinger, MD, FACS, associate professor of head and neck surgery at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said robotic surgery may lead to better techniques for accessing other difficult-to-reach locations in the neck, head and other confined areas.

“The traditional procedure [for thyroid surgery] is very safe,” Dr. Holsinger said. “I think the real leap forward will be to use robotic thyroidectomy as a stepping stone to more complex operations, neck dissection, for example, or even tracheoesophageal or laryngeal framework surgery.”

A Decade of Development

The “scarless” procedure was developed by South Korean surgeon Woong Youn Chung, MD, of Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul. Dr. Chung set out to find a way to perform thyroidectomy without causing the four-inch horizontal neck scar typical of traditional thyroid surgery. “Many Asian people, especially young women, don’t want to have a neck scar after surgery, because a hypertrophic scar is more frequent in Asian people,” Dr. Chung said in an e-mail.

Efforts to avoid the scar on the neck by performing thyroidectomy endoscopically have been ongoing for at least a decade in Japan, Korea and other Asian nations, but using a laparoscope to access the thyroid through a small, distant incision took longer and required more effort, Dr. Chung said. Also, the rigid and relatively unsophisticated instruments limited maneuverability. Such problems were largely resolved, Dr. Chung said, by performing the procedure using the da Vinci Surgical System manufactured by Intuitive Surgical of Sunnyvale, Calif. The system was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000.

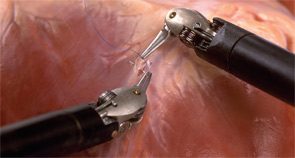

The da Vinci Si system allows the surgeon to operate three robotic arms simultaneously, while positioning a fourth arm to hold tissue in place. “Using three arms during the operation—one arm to hold tissue, one for drawing, and another for cutting and ligation—provides more dexterity than the two arms normally used in endoscopic surgery,” Dr. Chung said.

The robotic arms are fitted with forceps that enable the surgeon to hold, cut and cauterize tissue. The forceps are mounted on an EndoWrist developed by Intuitive to have seven degrees of movement and full rotation.

Sitting at a console several feet from the patient, the surgeon performs the surgery by operating the robotic arms while viewing the activity through the 3-D viewfinder with 10X magnification.

Safety Profile

Thom E. Lobe, MD, and colleagues at the Iowa Methodist Medical Center in Des Moines, Iowa reported the first use of a da Vinci surgery via an axillary incision in a 2005 paper (J. Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15(6):647-652). During the procedure, Dr. Lobe and colleagues retained the traditional technique of insufflating the area around the thyroid with carbon dioxide to create an operating space. The gas sometimes causes post-surgical discomfort and may lead to complications.

To avoid gas insufflation, Dr. Chung developed a special retractor that enables him to open a pathway between the incision in the armpit and the thyroid (Head Neck. 2010;32(1):121-126). His procedure involves placing the patient in a supine position and lifting one arm to expose the armpit. A vertical incision provides access over the pectoralis major muscle and clavicle, through the bloodless space made by the two branches of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, finally reaching the thyroid itself after detaching the carotid sheath from the lateral border of the strap muscles. Dr. Chung’s retractor is then inserted through the incision, creating a tunnel for three of the four robotic arms. A fourth robot arm gains access to the thyroid through a small incision in the chest.

During a 10-month period ending in July 2008, Dr. Chung and colleagues at Yonsei University performed thyroidectomy on 200 patients (192 women and eight men) using the da Vinci robotic arms through an axillary incision and the retractor to avoid insufflation. The mean time of the operations was two hours and 21 minutes, with the physician spending less than an hour at the console operating the robotic arms. Eight patients reported hoarseness, and one suffered damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, resulting in permanent loss of vocal cord movement. In their paper, Dr. Chung and colleagues concluded that the gasless, robotically assisted endoscopic thyroid surgery through an axillary incision “is both technically feasible and safe” (Surgery. 2009;146(6):1048-1055).

Gaining Ground in the U.S.

Although widely used for minimally invasive prostate and heart surgery, only recently have the robotic arms been applied to the confined spaces involved in neck and head surgery. In January, the FDA approved the device for transoral resection for pharyngeal and laryngeal cancers, a procedure developed by Gregory S. Weinstein, MD, and Bert W. O’Malley, Jr., MD, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. The two physicians founded the world’s first TransOral Robotic Surgery (TORS) program in 2004 and developed the TORS approach for a variety of robotic neck surgeries for malignant and benign tumors of the mouth, voice box, tonsil, tongue and other parts of the throat.

Surgeons in the U.S. are starting to adopt the procedure. Perhaps the most experienced is Ron Kuppersmith, MD, FACS, a clinical faculty member of the Texas A&M Health Science Center and an otolaryngologist with Texas ENT and Allergy. Last spring, he and a colleague, Andrew L. de Jong, MD, went to Korea and observed as Dr. Chung performed robotic surgery on the thyroid. Since returning, Dr. Kuppersmith has performed nearly two dozen such procedures (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(3):340-342). “Most cases I do are not robotic,” he said. “We’re very early in the experience, but the patients are excited about it. They’re asking about it. I had a patient call from Poland who wants to come and have the procedure, and we had one from Israel.”

The axillary approach is not for everyone, Dr. Kuppersmith said. “If the patient is obese, for example, it’s difficult. If the patient has trouble with range of motion in their shoulder, or if they have a large thyroid, or if the thyroid extends into the chest, or if they have a short neck, the procedure may not be appropriate. The anatomy has to be favorable,” he said.

Dr. Kuppersmith has found that some surgeons remain skeptical of the procedure because of the cost of the robotic system and the use of disposables. “That adds to the cost of a procedure that’s very good already,” Dr. Kuppersmith said. “In this health care environment, where everyone is being conscious of costs, does it make sense to use this really expensive tool to avoid having a neck incision? That’s a tough equation to work out.”

Simon K. Wright, MD, who co-authored the 2005 paper with Dr. Lobe on the use of the da Vinci robotic arms for head and neck surgery, also occasionally encounters a fellow physician with a negative opinion of robotic surgery, “but once a surgeon reviews the literature, understands the technique, and actually sees a case, the value of this option is more apparent,” he said. “Some patients are poor candidates for this type of surgery. I think everyone agrees, for example, that aggressive cancers of the thyroid gland shouldn’t be done this way at this time. Only a subset of patients undergoing thyroid surgery can be expected to benefit from this surgical approach, so the challenge at this point is to sort out who is an appropriate candidate.”

Emad Kandil, MD, FACS, chief of the Endocrine Surgery Section and assistant professor of surgery at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans, is a recent convert to robotic thyroidectomy, in part because of the technique’s potential for avoiding complications. “This technique is not only about avoiding an incision and a permanent scar on the neck,” he said. “With the excellent 10-times magnification, the danger of injuring nearby structures, including nerves and parathyroid glands, is reduced.”

Eliminating gas insufflation during the procedure avoids the complications associated with CO2 retention, such as retained subcutaneous air, pneumomediastinum and retained CO2 in the blood, which leads to hypercarbia and acidosis, Dr. Kandil said. Preliminary data show that patients undergoing this procedure report significantly less pain after surgery compared to patients undergoing traditional neck surgery (J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(2):e1-7). “Most probably this is related to the smaller number of nerve endings in the axilla area compared to the neck,” he said.

Dr. Holsinger, at least, believes robotic thyroidectomy will change the way head and neck surgery is performed. “In the next five years, with robotics as a common platform, I predict that we’ll design and perform several new and innovative procedures for head and neck surgery via transoral and transaxillary approaches,” he said.

Tom Valeo is a medical writer based in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Editor’s Note: None of the sources quoted in this article reported financial ties to Intuitive Surgical, the company that makes the da Vinci Surgical System.

Leave a Reply