Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) can fail for many reasons: patient/disease factors, anatomy, incomplete surgery, ostial stenosis, recirculation, neo-osteogenesis, and recurrent mucosal disease. When it fails, otolaryngologists may be tempted to perform another surgery. Before doing so, however, it is important to first develop a clear picture of the anatomy, assess for comorbidities and mitigating factors, and set realistic expectations for the patient.

Explore This Issue

November 2017“The frontal sinus can often be the most difficult and challenging to treat,” said Edward McCoul, MD, MPH, an otolaryngologist at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans, to a crowded room during a session at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. His session was dedicated to recognizing the various pathophysiologic processes that may contribute to refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and to describing the available medical and treatment options.

Approximately one-fourth of the patients who fail medical therapy and then undergo ESS will be diagnosed with refractory CRS. These patients will not make clinically significant improvements after surgery, and their symptoms cannot be controlled by appropriate medical therapy. They are more impaired than patients with Parkinson’s disease or moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). “It is a very impactful disease on the people who have it,” said Dr. McCoul.

Pathophysiology of CRS

Abtin Tabaee, MD, an otolaryngologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, acknowledged that scientists still do not know the role of the normal microbiome in sinusitis. They do know, however, that the host, environment, and microbiology all come together to influence CRS. For the most part, attention on the host has focused on the paranasal anatomy. Unfortunately, this has not always been helpful, because there are anatomical variants that occur at a similar rate in both healthy patients and patients with CRS. Thus, these apparent anatomical vulnerabilities must be only one piece of the puzzle. For example, it may be that the anatomy blocks outflow tract physiology and, in this way, serves as an obstacle to topical treatment. If so, then it is a reasonable target for surgery if indicated by disease.

The microbiology of the sinuses includes viruses such as rhinovirus, acute bacterial infections, chronic bacterial infections, and fungal infections. There is a growing recognition that these organisms can form biofilms, which are surface-associated bacterial/fungal communities that allow microbial survival in non-optimal conditions. Otolaryngologists also now realize that the paranasal sinuses are not sterile. Instead, they are populated with a natural microbiome of multiple commensal bacteria that may be protective. While this knowledge is important, many questions remain unanswered, perhaps the most important of which is how best to optimize the sinus microbiome.

Treatment Options

Peter Hwang, MD, professor of otolaryngology and chief of the division of rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery at Stanford University Medical Center in Calif., concluded the session by reviewing the available anti-inflammatory therapies and anti-infective therapies. Anti-inflammatory therapies include topical steroid irrigation, drug-eluting stents, and biologic therapies. Anti-infective therapies include both oral and topical agents.

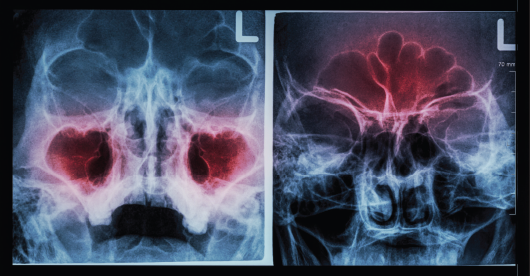

© Puwadol Jaturawutthichai / shutterstock.com

Dr. Hwang explained that nasal steroids are most effective when they are prescribed with customized dosing regimens that deliver higher doses topically, such as steroid eye drops delivered directly transnasally or diluted in normal saline. While these protocols may be the most helpful, he acknowledged that they are not without risk. For example, a 2016 report of 48 patients treated with budesonide for a mean of 22 months found that approximately one quarter of the patients had abnormally low stimulated cortisol levels (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:568–572). The risk of abnormal cortisol levels was associated with concomitant use of pulmonary inhaled steroids. Thus, while long-term use of budesonide nasal irrigations is generally safe, asymptomatic suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis may occur in selected patients. In particular, the investigators identified concomitant use of both nasal steroid sprays and pulmonary steroid inhalers while using daily budesonide nasal irrigations as the cause of the increased risk. The authors cautioned that rhinologists should be aware of the potential risks of long-term use of budesonide nasal irrigations and should monitor patients receiving this therapy for HPA axis suppression.

Otolaryngologists may also prescribe antibiotics in an effort to have a positive effect on the sinus microbiome. In some cases, the antibiotics are prescribed without any specific knowledge of the microbiome. In other cases, the physician cultures the microbes from the sinuses and prescribes culture-directed therapy. Unfortunately, it is not obvious that this culture-directed therapy provides an additional benefit to the patient.

While the scientific literature supports antibiotic therapy in general, the data are complicated. One study in support of culture-directed topical antibiotics evaluated 58 patients with recalcitrant CRS post-ESS (Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016;30:414–417). The patients were treated with culture-directed topical antibiotics and trended toward improvement in symptom severity. They also displayed improved appearance by endoscopy. Additionally, 72% of them had negative posttreatment culture results indicative of microbiological “control.” The results are consistent with the use of high-volume culture-directed topical antibiotics.

Dr. Pullen is a freelance medical writer based in Illinois.

Disclosures: Dr. McCoul is a consultant for Acclurent. Dr. Tabaee is a scientific advisor to Spirox. Dr. Hwang is a consultant with Medtronic.

Take-Home Points

- ESS can fail for many reasons, including patient/disease factors, anatomy, incomplete surgery, ostial stenosis, recirculation, neo-osteogenesis, and recurrent mucosal disease.

- Nasal steroids can be effective treatment for CRS, but they also are associated with risks.

- Culture-directed topical antibiotics may be helpful, although data are conflicting.