© Alan Poulson Photography / shutterStock.com

Editor’s note: This is part one of a two-part series examining the ways physicians prepare for and manage parental leave.

It’s logical to conclude that medical personnel enjoy the gold standard in employee healthcare benefits. That can be a risky assumption, however, especially for residents in their childbearing years. It isn’t unusual for young physicians planning a family to discover—sometimes too late—that their health benefits fall short of the minimum guidelines recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to ensure a healthy pregnancy (available at acog.org).

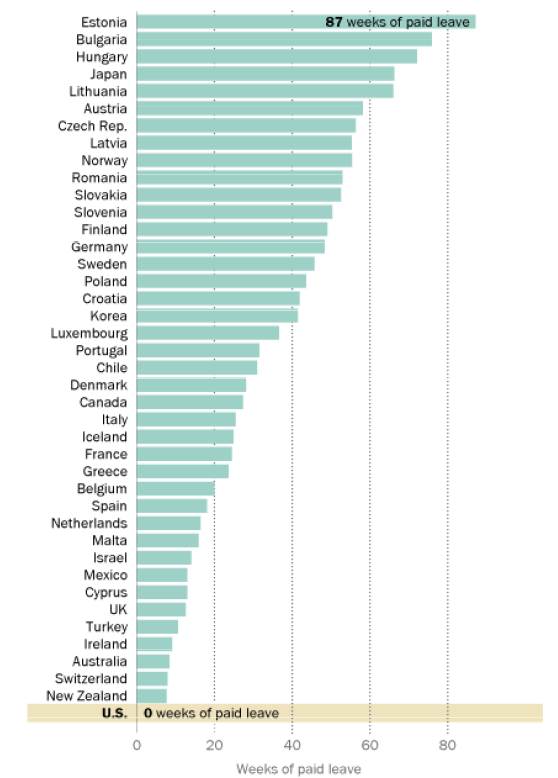

Other countries provide more benefits than the United States (see “Paid Parental Leave by Country”). This is especially true with maternity leave, as many healthcare employers have struggled to keep up with the growing status of women in the medical community.

According to data derived from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Data Warehouse, only 6.9% of medical school graduates in 1966 were women. By 1981, that number had risen to 24.9% and, in 2014, women comprised approximately 47.5% of all medical school graduates. Moreover, the American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA) reports that 50% of female physicians have their first baby during residency training. All of this amounts to dramatically increased numbers of women physicians growing their families and developing their careers simultaneously.

Medical residents are subject to the same challenges as employees in other professions. Meeting these challenges requires the cooperation of healthcare employers and employees in finding ways to ensure that adequate time and space is allotted to welcome new arrivals into the world, and doing so without jeopardizing the careers into which physicians have invested so much.

Best-Laid Plans

When Gayle Woodson, MD, an otolaryngologist at Ear, Nose, Throat, and Plastic Surgery Associates in Winter Park, Fla., entered the field in 1976, she was one of only 12 female otolaryngologists in the country. Dr. Woodson vividly recalls being asked during her medical school interview, “What will you do about children?” Taken by surprise, she replied, “Well, I guess I won’t have any.” She didn’t take herself at her word, however, and did indeed get pregnant during her fellowship. She went on to start her job during her eighth month of pregnancy and waded her way through a system that was not necessarily ideal for female physicians who wished to have children.

Dr. Woodson knows she was one of the lucky ones. “My boss was very progressive, and colleagues were protective of me, but I had a good friend at the time who was also pregnant and in private practice. Her group felt that she should pay for a locum tenens to cover for her [while she was out of the office], because it was unthinkable at the time, not only for a woman to be a surgeon, but for a woman surgeon to have a baby. Just unthinkable.”

“A lot depends on the kind of group you’re in. You hope that they’ll give you time off without call if you need it in late pregnancy, and that you can have enough time after the birth to stay at home without any clinical obligation. Some women want to come back and work part-time and some really want to go full force. You have to know what works for you and negotiate for it.” —Gayle Woodson, MD

Although female surgeons are no longer a rarity, it’s still not unusual for pregnant physicians to encounter obstacles as they navigate the logistics of maternity-related leave and scheduling adjustments. Often, the first hurdle comes when they have to interpret their program’s maternity benefits, said Kim Templeton, MD, president of the AMWA. “Not all employment contracts are the same, and physicians need to read them carefully to see if parental leave is included. If it isn’t, then that should be discussed prior to signing,” Dr. Templeton added. “Otherwise, these benefits are handled by federal law, which is written for everyone and doesn’t take into account issues of those in specific professions, such as medicine.”

Philip Dickey, MPH, is a partner and director of human resource services at DoctorsManagement, a full-service consulting and management firm for medical practices. Dickey stresses the importance of education and preparation in planning a family and a medical career. “One of the things we do in HR is keep people from being unhappily surprised about things,” he said. “That means availing yourself of the information and benefits available, including what the employer will provide in terms of time off and the processes and policies in place within that organization to make it happen. It means being a self advocate for you and your family.”

Residency is often a young physician’s first experience with an employment contract, after many non-earning, benefit-free years of medical school. She may not recognize the potential deficits implied in a vague reference to “paid maternity leave” or “paid parental leave” and may not consider a few key questions, such as:

- How much paid (and unpaid) leave time is provided?

- Does “paid” mean full pay or partial pay?

- Are these benefits specific to the program, or are they based on existing federal and/or state law options, such as the Family and Medical Leave Act and short-term disability?

- Is it possible for me to completely meet program criteria and take care of my and my baby’s needs?

- Does the program provide paternity leave, and what are the terms?

“Requirements for most, if not all, specialties state that residents need to participate in 46 out of every 52 weeks of each academic year,” said Templeton. “If a resident needs to take time off as a new parent, this needs to be planned ahead of time. If additional time needs to be taken, then training will be extended to cover this. Although this is feasible, it can place additional burdens on the training program, as they need to apply to have an additional resident for that period of time, secure funding to pay for the resident, etc. With funding for GME already extremely tight, this can be challenging.”

Growing Pains

(click for larger image)

Paid Parental Leave By Country

Number of weeks of paid parental leave by country. Totals include maternity leave, paternity leave, and parental leave entitlements.

Even with proper planning, managing maternity and residency can test the toughest among us, especially when facing a seemingly immovable object such as limited pregnancy leave.

Coral Tieu, MD, a fifth-year chief resident in otolaryngology at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine and St. John’s Hospital in Springfield, is currently pregnant with her third child and readily admits that her experience has tested the limitations of her time, energy, and ingenuity.

“I haven’t had many options because the ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education] is the body that governs time off. Six weeks a year is the maximum amount you can take and that includes sick time and vacations. With my second pregnancy, I took two weeks’ sick time and three weeks’ short-term disability, then couldn’t take vacations. Plus I had to make up calls for a year,” she said. “This time I’ll be taking five weeks’ maternity leave, and I’ve made up my calls in advance.”

Given the limits of official benefits, it is often incumbent upon the medical practice team to establish policies that are fair and cooperative. For numerous cultural and practical reasons, some specialties tend to be more flexible than others. Training programs in ob-gyn have led the pack in developing schedules to accommodate maternity. Drs. Woodson and Tieu both say that the culture of otolaryngology is more family-oriented than many other specialties; however, they note that other departments, such as general surgery, are much more rigid and tradition bound, recalling the days when pregnancy was regarded as an illness.

“A lot depends on the kind of group you’re in,” said Dr. Woodson. “You hope that they’ll give you time off without call if you need it in late pregnancy and that you can have enough time after the birth to stay at home without any clinical obligation. Some women want to come back and work part-time and some really want to go full force. You have to know what works for you—and negotiate for it.”

Ensuring a smooth and positive maternity experience requires thinking about how maternity leave affects patients, fellow physicians, and the rest of the clinical staff. “Obviously, the nurses who work for a physician planning to go on leave want to know whether they’re going to have a job while that doctor is away, whether there will be reduced hours and if there will be a forced vacation,” Dickey said. “The schedule may be divided among the remaining physicians [or] given to a locum tenens, or the number of patients will need to be reduced. Keep in mind that the providers are the producers, and what they do affects the practice’s bottom line.”

So, which is preferable? Having a child while in residency or waiting until you’re in practice? As any parent will attest, there is no ideal time. Dr. Tieu feels that, because residency is so intense, it might be better to wait until afterward if possible, as long as you’re young enough. Dickey points out that interns and residents work such long hours that going on leave might be hardest then.

“We’re all wound a little different, so I think it falls back to being introspective, knowing ourselves, and not going in blind,” added Dickey. “After all, having a family is supposed to be a happy experience.”

Part 2, which will publish in the April issue of ENTtoday, will look at ways medical practices can accommodate new parents returning to the workplace.

Linda Kossoff is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Parental Leave During Medical Residency

In the era of duty-hour reform and physician burnout awareness, medicine has made important cultural strides towards recognizing the value of maintaining balance between professional and personal life. Additionally, it is impossible to ignore the fact that—much to the perceived disbelief of our predecessors—the joyful and sometimes tragic unpredictability of life is not suspended during residency (or medical school, for that matter).

The medical community has also come to acknowledge the vocational value of life-shaping events. There is general understanding that experiencing loss, overcoming acute illness, and coping with chronic disease are all examples of formative experiences that deepen a physician’s empathy and overall emotional intelligence in delivering patient care. Similarly, the rite of passage into parenthood is associated with uniquely challenging (but amazing) maturation, vulnerability, and perspective that enrich one’s insight as a clinician.

While the logistical challenge of accommodating leaves of absence requires careful planning, residency programs are well-equipped to meet the needs of their trainees, including those individuals choosing to become parents. —Nathan E. Derhammer, MD, program director of the Combined Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Residency Program at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill.

From: AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:116-119.