Thankfully, emergencies are rare in the otolaryngology office setting. But, as more and more procedures move from the operating room to the office—including balloon sinuplasty, endoscopic procedures and skin cancer reconstruction—the potential for in-office emergencies increases. Are you adequately prepared?

“It’s absolutely essential to have a plan, equipment and emergency procedures in place so that you’re well-prepared when something happens, because it will happen at some point,” said Brad DeSilva, MD, residency program director in the department of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery at Ohio State University in Columbus.

All otolaryngologists in private practice should be equipped for and prepared to handle airway emergencies and excessive bleeding, the two most common otolaryngology-related emergency scenarios. Additional emergency preparation will depend on your area of practice. An otolaryngology office that offers allergy shots, for instance, must be prepared to handle anaphylactic shock.

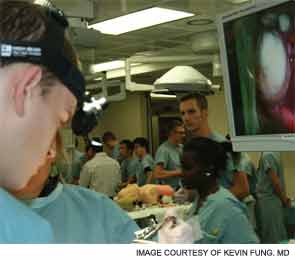

Pre-planning and practicing your response are essential. “These are life-saving, high-stakes, time-sensitive and clinically important skills,” said Kevin Fung, MD, an otolaryngologist at London Health Sciences Center in Ontario and one of the organizers of “Emergencies in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Bootcamp.” The bootcamp, held last fall, included faculty and junior residents from 10 U.S. and Canadian universities and hospitals. “The simulation-based bootcamp trained first- and second-year residents specializing in otolaryngology emergency life-saving skills before they experienced life-threatening situations during their residency,” said Dr. Fung.

Emergency Prevention

The first step of emergency preparation is figuring out how to avert a crisis. Careful selection of patients can help you avoid unnecessary in-office emergencies.

“You don’t want to see patients in your office that you can’t handle if anything goes wrong,” said Hootan Zandifar, MD, an otolaryngologist who specializes in facial plastics and reconstructive surgery at the Osborne Head and Neck Institute in Los Angeles. “Pre-selecting your patients prevents a lot of issues.”

Consider your patients’ overall health. Be aware of issues such as high blood pressure or use of anticoagulants. “If your patient is on a blood thinner, he may become more than you can handle in the office,” Dr. Zandifar said. “You don’t want to do a procedure on a patient like that in the office, where you have limited help available.”

It’s also important to assess your patients’ anxiety and comfort levels. “I always try to judge a patient’s comfort level with the procedure while they’re still awake,” Dr. Zandifar said. “Sometimes an endoscopic procedure can cause a vasovagal response that causes the patient to pass out. I can almost judge which patients this will happen to, based on their level of anxiety about the procedure. So, before I schedule a patient for an office procedure, I first make sure that they can tolerate it and are not excessively worried about it.”

If the patient seems particularly nervous or worried about pain control, it may be better to schedule OR time, even if the procedure is one you normally perform in office.

Airway Emergencies

Airway emergencies, while rare in office settings, obviously merit tremendous concern. “When it comes to emergencies, the one thing that makes our specialty unique is that the area we service includes the airway, so airway emergencies are always something that we worry about,” Dr. Zandifar said. Possible causes of an in-office airway emergency include bleeding into the airway, swelling or inflammation related to an infectious process or allergic reaction and laryngospasm.

An airway obstruction can also occur during routine tracheostomy changes. “Occasionally, especially in children, you lose the airway when you remove the tracheostomy tube. The tract closes and doesn’t have the same path you’d expect it to,” said Dr. Zandifar. “The first thing you have to do is to stay calm. Remember that you have the skill set to solve the problem.”

If the tracheostomy tract seems to have closed up, try inserting a smaller trach tube. “I’ve used smaller tubes than the one that the patient had previously to get through,” Dr. Zandifar said. “I let that sit there for a few minutes, let the patient breathe, then take out the small tube and put in one that’s a little bigger—essentially serially dilating the tract.”

Every otolaryngology office should have basic airway resuscitation equipment on hand: oxygen, an Ambu bag, oral airway, nasal airways and intubation equipment of various sizes. “Intubation equipment is particularly important if you’re doing facial plastics or biopsies of the tongue or nose,” Dr. Fung said.

Keep in mind that bigger is not always better when it comes to intubation. “The idea still floats around that someone who is obese may need a bigger tube,” said H. Steven Sims, MD, director of the Chicago Institute for Voice Care. “The reality is that a woman who is 5’2” and 250 pounds probably still has a small airway.” And, while securing the airway is always the number one concern, using a tube that’s too big can cause trauma to the vocal cords, which may result in unwanted sequelae.

“If you put a big tube in, then as soon as possible, see if you can exchange it for a smaller one,” Dr. Sims said. “If it’s still needed after 48 hours, consider converting to a trach.”

Bleeding Emergencies

Bleeds are far more common in office than airway obstructions. Some patients experience excessive bleeding during an office procedure; others walk in with uncontrolled epistaxis. In both cases, the goal remains the same: Control the bleeding.

All otolaryngology offices should have nasal packing material on hand. Dr. Zandifar also recommends pro-coagulating material such as Floseal and Gelfoam. Cautery equipment is also useful, as is a blood pressure monitor. Some offices also have intravenous supplies ready, in case the patient needs IV hydration to restore fluid volume.

Careful preparation may decrease the number of bleeding incidences you experience—and increase your ability to handle them efficiently.

“I’ve found that talking to my patients, letting them know that there may be some bleeding but that they’re okay, makes patients more comfortable and decreases their blood pressure, which definitely helps with bleeding,” Dr. Zandifar said.

It’s also helpful to expect bleeding. “When a patient comes in after an ER visit and needs nasal packing removed, I never approach it as, ‘I’m going to take this out, and it’s going to be fine.’ I always approach it thinking, ‘I’m going to take this out, and they’re going to bleed on me,’” Dr. Zandifar said. “I wear a gown and face shield and have the patient wear a gown. And I have all the equipment I might need right there—a headlight, cautery equipment, packing material. If I take the packing out and nothing happens, great. But if the patient bleeds, I definitely don’t want to be underprepared.”

If possible, have an assistant in the room with you. The assistant can hand you supplies and escort out family members, if necessary.

Allergy-Related Emergencies

Otolaryngology offices that offer allergy services must be prepared for the possibility of an allergic reaction. “If you’re going to be doing allergy shots in your practice, or if you’re going to be escalating immunotherapy, it’s important to have a trained physician on site at all times who can handle an emergency,” Dr. DeSilva said. “If someone has an acute allergic reaction, you don’t want to leave a patient with a technician who doesn’t know how to handle those types of situations.”

It’s also essential to have epinephrine, steroids and oxygen readily available.

Work Together

Emergency plans should be reviewed frequently with all staff members. “We have regular meetings to remind everyone where the crash cart is, where the oxygen is and how to handle the emergency equipment,” Dr. DeSilva said. “We also talk through emergency situations. We might review what to do if someone has a heart attack in our office, for instance. We’ll go through the ACLS [advanced cardiac life support] steps so that everyone is on board and knows what to do if that situation arises.”

Dr. Zandifar’s office has an annual emergency training meeting; common emergency scenarios are also reviewed during weekly lectures with staff members.

Post-emergency debriefings are also helpful, whether the emergency was real or simulated. “When we conducted our simulation-based emergency boot camp, we found that the debriefing was one of the most important parts,” Dr. Fung said. “If a scenario took ten minutes, we’d spend 20 minutes talking about it afterward. The faculty and learners would sit around a table and talk about what went well, what didn’t go well and what could be done better next time.” A similar approach can work in an office setting.

Be sure that all staff members understand their role in emergency preparation. Beyond responding to emergency situations, a nurse or medical assistant may be responsible for monthly checks of the crash cart and emergency supplies. All staff should be up to date on emergency certifications, including basic life support and ACLS, as appropriate.

Physicians should also practice their leadership and collaboration skills. Successfully responding to an emergency involves more than clinical skills; it “also has to do with how you communicate and collaborate with other members of the health care team,” Dr. Fung said.

“Learn to be a better leader,” he said, “because you never know what kind of disaster you’re going to get in your clinic.”

Leave a Reply