Harnessing the power of the immune system to fight advanced head and neck cancers topped the list of breakthroughs for several otolaryngologists who were asked to identify recent research that has transformed clinical care.

Explore This Issue

February 2020But that excitement is a relatively new development for the profession. Indeed, for many years, otolaryngologists could not be blamed for feeling like they’d been left on the sidelines while immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies scored victories against a wide range of malignancies.

“Think about it: For years, cisplatin had been our primary chemotherapy drug for head and neck cancers, even though it was first approved in 1978,” said Jennifer R. Grandis, MD, professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. “And while cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, was approved in 2006, after 13 years of clinical use, it’s been a bit of a disappointment in terms of achieving any major gains in survival.”

© Science Photo Library / offset

That’s why the more recent approvals of pembrolizumab and nivolumab are such a promising development for patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), Dr. Grandis told ENTtoday. “It now gives the multidisciplinary team of medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and head and neck surgeons two new tools for augmenting the immune system to target the cancer, rather than having to rely on more highly toxic regimens.”

The efficacy of pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp.), a programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) inhibitor, is a case in point, as evidenced in the KEYNOTE-048 trial that led to the drug’s full approval for HNSCC in 2019 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02358031). The median overall survival (OS) was 13.0 months for the pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy arm and 10.7 months for the cetuximab plus chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio [HR] 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.63, 0.93; P=0.0067), according to a U.S. Food & Drug Administration press release announcing the approval. In a subgroup of patients with high PD-L1 expression, the OS difference was a bit more pronounced: 14.9 months for the pembrolizumab arm versus 10.7 months for the cetuximab plus chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.45-0.83; P=0.0015), according to the FDA.

The benefits of nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol-Myers Squibb) tell a similar story. Approved in 2016 for patients with HNSCC that has progressed or metastasized after platinum-based chemotherapy, the drug has achieved some of its most impressive OS gains in the CheckMate 141 trial (Oral Oncol 2018;81:45-51). The drug “nearly tripled” OS rates at a minimum of 24 months (16.9%) versus standard therapy (6.0%), first author Robert L. Ferris, MD, PhD, the director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, told ENTtoday.

Think about it: For years, cisplatin had been our primary chemotherapy drug for head and neck cancers, even though it was first approved in 1978. —Jennifer R. Grandis, MD

The drug also demonstrated an OS benefit across the spectrum of PD-L1 expression: ≥1% (HR [95% CI] = 0.55 [0.39-0.78]) and < 1% (HR [95% CI] = 0.73 [0.49-1.09]). Moreover, the OS benefit was seen regardless of tumor human papillomavirus (HPV) status. “In the earlier PD-L1 studies, the initial response rate for HPV-positive cancers was faster and more frequent, but when you look at the long-term data from the CheckMate 141 trial, the HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients had essentially identical survival rates,” Dr. Ferris said.

According to Dr. Ferris, one question has been at the core of studies evaluating immune checkpoint inhibitors for advanced HNSCC: Are they ready to assume first-line status for recurrent or meta static disease, or at the least be used in conjunction with standard-of-care chemotherapy? “As I noted in my recent Lancet article [2019;394:1882-1884], the answer, in short, is yes to both questions,” he said.

Education Is Key

Otolaryngologists can help ensure these new immunotherapy drugs have the maximum chances for success “by becoming immune-literate,” Dr. Grandis said. “Head and neck surgeons need to understand these immune pathways and what these drugs are doing, what they are not doing, and cement partnerships with our medical and radiologist oncologists to pull in the same direction.”

Dr. Ferris agreed. “HNSCC is a unique cancer because about half of cancers are carcinogen-exposed tumors [smoking, alcohol] and half are virus-induced tumors [HPV and Epstein-Barr virus], making HNSCC a unique model to understand why immunotherapy works for some, but not most, patients,” he added.

In addition, “ENT surgeons see the patient first, and obtain the pre- and post-treatment biopsy specimens,” he said. “So ENTs are in unique position to help our colleagues in medical oncology understand how these PD-1 inhibitors are working or not working in real time. By analyzing pre- and post-treatment biopsies, we can better understand responders and non-responders, biomarkers, and resistance pathways in head and neck cancers—potentially applicable to other malignancies.”

Dr. Ferris pointed to another reason why otolaryngologists would benefit from brushing up on their understanding of key immunotherapy concepts: They may find themselves taking on an even more active role in the care of these patients. “Within our lifetimes, I would suggest that we may also be giving the PD-1 inhibitors, because there are oral and subcutaneous versions coming on the market that look promising,” he explained. “It may be that the head-neck surgeons give the antibodies themselves in their office, which makes sense, since the ENT actually sees the patient first. So ENTs need to be aware of these developments—this is not just restricted to medical oncologists.”

Changes in AJCC Guidelines

Another development has been the release of American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines for the treatment of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas, said Maie A. St. John, MD, PhD, the Thomas C. Calcaterra Chair in head and neck surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

The new guidelines (CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:93-99) feature modifications and additions to staging head and neck cancer that were the result of “a multitude of studies,” said Dr. St. John, who is also co-director of the UCLA Head and Neck Cancer Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. These include using depth of tumor invasion as a criterion for T designation, as well as novel staging systems for high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive cancers, and the inclusion of extranodal extension.

Within our lifetimes, I would suggest that we may also be giving the PD-1 inhibitors, because there are oral and subcutaneous versions coming on the market that look promising. —Robert L. Ferris, MD, PhD

“We knew from clinical experience and studies that patients with HPV-positive tumors had better outcomes than patients with HPV-negative tumors,” Dr. St. John said. “The new guidelines create a separate staging system for HPV-positive tumors, allowing more precise therapy for these patients. With advances in immunotherapy, a multitude of new possibilities are now in the pipeline for treating recurrent and metastatic head and neck tumors.”

Dr. St. John agreed with Dr. Grandis that treating head and neck cancers requires real-time multidisciplinary care. “A increasing number of institutions have signed on to this, where patients come in and are seen by a multitude of specialists in one afternoon,” Dr. St. John said. That strategy is also driven by the complexity of head and neck cancers. The tumors “occur in an anatomical region unmatched in the number of physiological functions potentially affected,” she explained.

Dr. St. John cautioned, however, against taking too narrow an approach. “The care of the head and neck cancer patient is the art of caring for the whole patient,” she said. “That should include multimodal surgical and medical management, aesthetic considerations, nutrition, pain management, and psychosocial support.”

Nikki Kean is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Farther Afield, Hints of NF2 Breakthrough

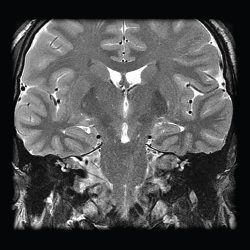

© Living Art Enterprises, LLC / Science Source

For some head and neck tumors, identifying signs of progress may require looking a bit beyond the core otolaryngology literature.

That’s certainly the case with schwannomas and meningiomas caused by neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), a rare tumor suppressor syndrome, according to D. Bradley Welling, MD, PhD, who helped discover the genetic mechanisms of the rare disorder.

Dr. Welling, Walter Augustus Lecompte Professor and chair of Harvard’s department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery in Boston, pointed to a spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1) trial that yielded “remarkable, life-altering results” (N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1713-1722).

Patients with SMA1 fail to achieve key motor milestones and often need mechanical ventilation by two years of age. The disorder is caused by a mutation in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, which codes for SMN, a protein necessary for motor neuron function. The rare mutation is fatal in about 90% of patients by 10 months of age, Dr. Welling noted.

In the SMA1 study, 15 patients were given a single low- or high-dose infusion of a viral vector containing DNA aimed at replacing the SMN1 gene. By the end of the study, all 15 patients were alive and event free at 20 months of age, compared with an 8% survival rate in a historical cohort, reported the investigators, from Nationwide Children’s Hospital and The Ohio State University, both in Columbus.

The most impressive results were seen in 12 patients given the high-dose regimen: 11 sat unassisted, nine rolled over, 11 fed orally and could speak, and two were able to walk independently. Dr. Welling noted that in a follow-up study of 100 infants, two infants died, and the researchers reported gains in motor function in other infants (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03306277).

In May 2019, the FDA approved the gene therapy (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi; Zolgensma, AveXis) in children with SMA.

Asked why the SMA1 study resonated so much with him, Dr. Welling replied, “It is because of the researchers’ success in transporting a gene into the central nervous system. This is exactly what we hope to achieve for our NF2 patients.”

The stakes are high for success, he stressed. “NF2 shortens the lifespan of those affected and has profound effects on quality of life, resulting in facial paralysis, hearing loss, inability to communicate, disequilibrium, and spinal cord tumors that may cause aspiration and other potentially life-threatening problems,” Dr. Welling explained. “So, it’s a very important condition for us to overcome, and certainly part of the reason why these tumors have been such a strong focus of our research through the years.”

As for NF2 gene therapy, a breakthrough may come via large-animal models, such as the NF1 minipig model, Dr. Welling noted. The animal model “has shown a phenotype remarkably similar to humans with NF1,” including café au lait macules, neurofibromas, and optic pathway gliomas (Commun Biol. 2018;1:158 [doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0163-y]), he said. Such research “may be the key to achieving the advances necessary for gene therapy to get at the root of NF2.”