pathdoc/shutterstock.com

A recently published study involving patients with head and neck cancer adds to and confirms a growing body of data showing that depression contributes to premature mortality in general, as well as in patients with cancer in particular.

In the study, investigators from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston found that depression was a significant, independent factor predicting five-year survival in patients with newly diagnosed oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer (Psychosom Med. 2016;78:26-37).

Previous studies have also concluded that depression can be a predictor of mortality in patients with cancer (Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008; 5:466-475; Cancer. 2009;115:5349-5361).

In a review by Chida and colleagues of 165 studies that included patients with head and neck cancer as well as other cancer types, stress-related psychosocial factors were found to be significantly associated with poorer survival in patients with cancer in 330 studies and higher cancer morality in 53 studies (Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:466-475).

Data on the relationship between psychological distress and premature death are reliable and cut across all illnesses, including cancer, according to Barbara Andersen, PhD, professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, who has written extensively on this topic. She emphasized, however, that patients with head and neck cancers may be at particular risk of depression. “These patients tend, on average, to have lower economic and prior educational resources upon which to draw and, along with a smoking history, may have been heavy users of alcohol,” she said. “All of these factors complicate the picture, making it more difficult to cope with the diagnosis and the very difficult, life-changing treatments that follow. Prognoses are oftentimes poor.” Among all cancer patients, these patients are likely to be the most at risk for depression, social isolation, and premature death, she added.

Given the evidence of the connection between depression and premature death in patients with cancer, and the heightened risk in patients with head and neck cancers specifically, otolaryngologists can play a vital role in helping patients manage their cancer and the psychosocial difficulties that can accompany it—which can have a positive impact on rates of mortality.

Depression Can Impact Survival in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer

The most recent data showing increased mortality in depressed patients with oropharyngeal cancer come from the first study to examine the association of depression and mortality risk in cancer patients by focusing on only one type of cancer (Psychosom Med. 2016;78:26-37). According to Eileen Shinn, PhD, assistant professor of behavioral science at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and lead author of the study, focusing on one cancer type allowed for a cleaner, more homogenous sample that permitted a more level playing field for comparison of all the different factors that could affect outcome. The study also followed patients for five years, enough time for outcomes to develop. The researchers aimed to examine the effects of depression on tumor progression as well as mortality.

igor.stevanovic/shutterstock.com

The study included 130 patients with nonrecurrent, newly diagnosed oropharyngeal cancer, most of whom had late stage disease (91% head stage III-IVb disease). Most patients were male (83%) with an average age of 56 years. All patients received optimal doses of radiation and, if warranted, optimal doses of chemotherapy (the treatment team decided to give chemotherapy to patients with more extensive baseline disease). To screen for depression, researchers administered the Physicians Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to all patients at the beginning of their treatment with radiation therapy.

At a median follow-up of five years, 112 patients (86%) were alive and 18 (14%) had died either from cancer or treatment complications. After adjusting for tumor stage, age, sex, smoking status, excessive alcohol use, number of comorbidities, and addition of chemotherapy to the standard protocol of radiation therapy, the study found that patients who were depressed at the beginning of treatment had a 3.6 times higher risk of dying within five years than patients who were not depressed. [Note, the study did not control for human papilloma virus (HPV) status because HPV typing was not yet standard of care when the study was designed.]

When analyzing whether depression increased the risk for cancer recurrence, the study found that depressed patients had a 3.8 times higher risk of disease recurrence than nondepressed patients. “When you control for all traditional treatment and disease variables, depression was the most significant variable,” said Dr. Shinn. The study highlights the need to screen all patients with newly diagnosed oropharyngeal cancer, she said.

Depression Screening as Part of Psychosocial Screening

Depression screening is not only good medicine; it is now a mandate for cancer programs accredited by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC). Starting in 2015, cancer programs that want to earn or maintain CoC accreditation must include psychosocial distress screening, which includes screening for psychological issues such as depression and anxiety, for patients with cancer as mandated by CoC standard 3.2 (American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care 2015; Available at: facs.org).

The mandate carries significant challenges for cancer programs, according to Jeff Kendall, PsyD, clinical leader of oncology supportive services at the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who has been running such a program since 2011. The two major challenges, he said, are finding the expertise and resources needed to screen every cancer patient as well as those needed to address any psychosocial problems that are identified.

But meeting the challenge is critical, particularly for otolaryngologists. Echoing Dr. Andersen, Dr. Kendall also highlighted the particular psychosocial needs of patients with head and neck cancer. “Head and neck cancer patients as a whole have significantly more psychosocial issues than other cancer sites,” he said. “So otolaryngologists as a group need to do this screening and have the resources available for follow-up more than other cancer sites.”

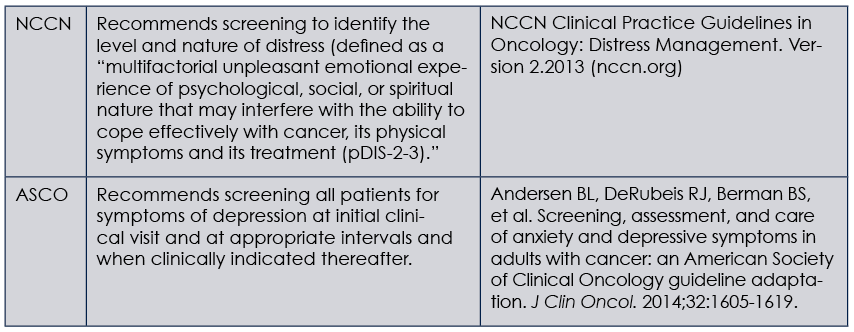

A number of resources are available to help integrate depression screening into routine cancer care. Among these are guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

(click for larger image) Guides for Depression Screening in Cancer Patients

NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology

Both of these guides offer algorithms on how to screen cancer patients for depression, as well as how to determine the next evaluation and treatment paths. A key determination that screeners need to make is which measure to use to screen for depression. Unlike the NCCN guidelines, which use a Distress Thermometer that covers a broad range of issues including but not limited to depression and anxiety, the ASCO guidelines recommend using tools designed and validated for depressive symptom assessment.

Dr. Andersen, who co-chaired the guideline panel, emphasized the recommendation to use the PHQ-9 measure as the most appropriate measure, as well as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder

seven-item (GAD-7) measure for anxiety symptoms. “These measures are validated and have been used successfully in many settings, including primary care,” she said. “Plus they correctly identify symptoms of anxiety and depression for which we have evidence-based treatment. The concept of distress is, unfortunately, vague and does not direct one to specific treatments.”

Dr. Shinn, who used the PHQ measure in her study, also recommended using this measure for depression screening, given its strong evidence base and psychometrics.

Dr. Kendall, who has previously used the NCCN Distress Thermometer to screen for distress in patients with cancer, said that the tool captures depression well. “If screening indicates that a patient is depressed, then referral for an assessment that can lead to an intervention is needed.” He stressed, however, the need to differentiate screening from assessment, saying that screening is only the first step and that the Distress Thermometer does a good job of screening. It is not an assessment tool, however; it only identifies patients for whom further assessment is recommended.

Both Dr. Andersen and Dr. Kendall believe that a major challenge for physicians is knowing where to refer patients when screening indicates they may need follow-up for depression. “The ASCO guidelines specify that referral for further evaluation of appropriate treatment is needed to address specific symptom levels,” said Dr. Andersen. “The challenge is for providers to identify specific referral resources in their facility and their community.”

Both recommend that physicians look carefully at the resources within their institutions, as well as in the community, and establish relationships, just as they do for any other referral pathway. “The longer-term issue is the need for more resources and more trained professionals, such as psychologists and social workers, within cancer programs,” said Dr. Kendall. “We’ve all been mandated to do distress screening, but there has been no money allocated to do that.”

To help otolaryngologists implement screening as well as develop referral pathways for assessment and treatment, Dr. Kendall also suggested seeking guidance from organizations that understand these issues. Recently, a joint task force comprising the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), the Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW), and the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) developed consensus-based recommendations based on six components of the CoC Standard 3.2 (Cancer. 2014;120:2946-2954), including:

- psychosocial representation on the cancer committee with a committee meeting that includes plans for screening;

- timing of screening;

- method and mode of screening;

- tools for screening;

- assessment and referral; and

- documentation.

Screening is just the first step to address potential depression in patients with cancer, but because referral for further assessment and treatment is needed for patients once they have been screened and identified with depression, clinics should put in place referral pathways prior to screening to ensure optimal treatment.

Prophylactic Treatment of Depression

Another approach that clinicians may think about is the use of prophylactic antidepressants to reduce the risk of cancer patients developing depression. This was suggested in a study by Lydiatt and colleagues, who found that prophylactically treating nondepressed patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer reduced the risk of depression by more than 50%, and that patients who were treated and were not depressed reported significantly better quality of life for three months after stopping the antidepressant (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:678-686).

William Lydiatt, MD, professor and vice chair of the department of otolaryngology and director of head and neck surgery at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, said that both initial screening for depression and prophylactic antidepressants in nondepressed patients with head and neck cancer should be employed. “Initial screening should be done to determine if the patient is already depressed,” he said, noting that up to 15% of people are depressed at baseline and will have a worse prognosis.

“If the patient is not depressed, they should be offered prophylaxis to prevent emergent depression,” he said. “If they decline, they should continue to be monitored.”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

What to Ask Your Patients about Depression

Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

- Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much

- Feeling tired or having little energy

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down

- Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television

- Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed, or the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual

- Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way

If you checked off any problems, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?

Source: Adapted from the PHQ Nine-Symptom Depression Scale (J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1605-1619).