milias1987/shutterstock.com

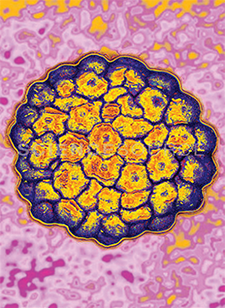

CHICAGO—In general, the prognosis is good for patients with oropharyngeal cancer. In particular, tumor human papillomavirus (HPV) status is a strong and independent prognostic factor for survival among these patients. HPV status is also associated with progression-free status, suggesting that HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas are distinct diagnoses, with different causes and risk factor profiles.

Explore This Issue

July 2016Research has also shown that HPV-16 is strongly coupled with the neoplastic process and that its presence is compellingly associated with oropharyngeal cancer. In an analysis published in 2005, Shahnaz Begum, MBBS, PhD, assistant professor of pathology at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and colleagues found that viral integration does not occur through the tonsillar epithelium as a field integration. Instead, p16 expression is intrinsic to the crypt epithelium and is sharply demarcated from the surface epithelium (Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5694-5699). P16 expression also localizes to HPV-positive cancers. The findings led Dr. Begum and colleagues to suggest that evidence of HPV-16 integration may be a meaningful finding for risk assessment, early cancer detection, and disease surveillance. In contrast, high p16 expression may not be particularly meaningful.

Additionally, research published in 2010 by Kie Kian Ang, MD, PhD [deceased], formerly a radiation oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and colleagues revealed a strong agreement between tumor HPV status and expression of p16, an established biomarker for the function of the HPV E7 oncoprotein (Head Neck. 2010;32:829-836). “Our data clearly indicate that HPV status and status with respect to tobacco smoking are major independent prognostic factors for patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, probably because they determine the molecular profile of the cancer and thus the response to therapy,” wrote the authors in their paper. “Although HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is genetically distinct from the HPV-negative cancer with respect to patterns of loss of heterozygosity, chromosomal abnormalities, and gene-expression profiles and is inversely correlated with biomarkers for a poor prognosis in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (mutations or expression of epidermal growth factor receptor), no specific mechanism has been shown to explain the higher rates of response to radiation therapy and chemotherapy among patients with HPV-positive cancer. Epidemiologic data indicate that tobacco smoking is not a strong cofactor for the development of HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous-cell carcinoma.”

While Dr. Ang and his colleagues went on to propose that the higher survival rate among patients with HPV-positive cancer is due, at least in part, to greater local-regional control in response to treatment, they acknowledged that there was little evidence to support the hypothesis that the superior survival of patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is dependent on the chosen therapy. In fact, in their trial, the researchers found that a concomitant boost accelerated-fractionation regimen of radiotherapy was no more effective than a standard-fractionated regimen combined with concurrent, high dose cisplatin. The authors concluded their paper by acknowledging that there is very little direct evidence that can be used to guide treatment decisions for individual patients on the basis of tumor HPV status.

Treatment De-Escalation

Given the absence of evidence to direct treatment and the generally good prognosis for these patients, is it reasonable for physicians to de-escalate treatment? If so, which patients are good candidates for de-escalation? Should de-escalation be determined based upon HPV status, HPV subtype status, p16 status, or something else altogether? These questions formed the basis of a panel discussion held during the Triological Society annual meeting on high risk HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer.

Robert L. Ferris, MD, PhD, endowed professor and chief of the division of head and neck surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh, reported that the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) is in the process of addressing these questions in a clinical trial of participants with HPV-positive stage III-IVA oropharyngeal cancer. The trial is designed to compare the effects of transoral surgery followed by low-dose or standard-dose radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. In particular, the randomized phase II trial should determine how much extra treatment should be given after surgery. The primary outcome is the proportion of patients alive and progression-free at 24 months.

Until the trial is complete, the panel acknowledged that, in most cases, there is no single correct treatment path. Instead, they noted certain situations that raised concerns. For example, Dr. Ferris raised the issue of pathology in both tonsils. “About 10% of the time, both tonsils have disease,” he said. “I don’t think we can turn away [from] or turn toward a particular modality.… We shouldn’t move away from surgery just because the other tonsil has disease. Tumor burden is the key.” The panel agreed that all cases involving the base of the tongue are worrisome because of data on what is going on in the opposite neck.

Dr. Ferris also discussed the subject of patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer who have distant metastases, noting that “traditional FDA-approved chemotherapies don’t have any way to help us at the moment; immunotherapies hold promise to change this.”

Molecular Markers

Dr. Ferris elaborated on the hypothesis that patients with HPV-positive cancer are distinct from those with HPV-negative cancer who often also happen to be smokers. He said that while there is controversy about smoking, “For now, we think smokers have a worse prognosis.” He focused the panel’s attention on these HPV-negative patients, describing them as the true high-risk group.

Cherie-Ann Nathan, MD, vice chairman and director of head and neck surgical oncology and cancer research at Louisiana State University in Shreveport, expanded the conversation to the numerous additional molecular markers that could theoretically be used to stratify risk. These molecular markers include p16 expression, PIK3CA mutations, and PTEN loss, as well as copy number variations in certain chromosomal loci. The molecular markers may actually reflect a mutational burden from smoking, since tobacco exposure may trigger other mutations. Looking to the future, the panel agreed that the best way to stratify risk may ultimately be to integrate some of the molecular modifications.

Lara Pullen is a freelance medical writer based in Illinois.

Take-Home Points

- Patients with oropharyngeal cancer have a good prognosis.

- The possibility of de-escalating treatment is currently being evaluated in a clinical trial of participants with HPV-positive stage III-IVA oropharyngeal cancer.

- HPV-positive cancers are likely distinct from HPV-negative cancers, which are often associated with smoking.

- In the future, detailed analyses of molecular modifications may be used to stratify risk and direct treatment of oropharyngeal cancer.