decade3d – anatomy online/shutterstock.com

Chronic (CRS) and acute (ARS) rhinosinusitis affect many people: Nearly 29.4 million U.S. adults have been diagnosed with sinusitis, and 11.7 million visits to physician offices resulted in a primary diagnosis of CRS, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Explore This Issue

May 2016The sheer amount of information available about ARS and CRS pathology and treatment is staggering, however, and the condition continues to be the subject of ever-widening research.

To help clinicians and researchers better find evidence-based information, the International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology recently published the “International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis (ICAR:RS).” The statement examines more than 140 topics relating to rhinosinusitis (RS), reviewing evidence-based studies and making recommendations based on that evidence (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:S3-S21).

“By virtue of its timing and systematic approach, this manuscript has incorporated the most recent scientific studies and prior position papers, combining prior perspective with current literature,” said Abtin Tabaee, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. “The authors have taken a comprehensive approach both in terms of the depth of the literature reviewed and the various diagnostic and treatment subtopics discussed, including the full spectrum of CRS diagnosis, medical therapy, surgical procedures, and postoperative care. By reviewing more of the relevant individual aspects of evaluation and treatment for CRS, the authors have expanded common critical aspects, such as antibiotics, to a more broad and encompassing conversation.”

Evidence-based pathology and guidelines are given for acute ARS, CRS both with and without nasal polyps (CRSwNP and CRSsNP), recurrent ARS (RARS), acute exacerbation of CRS (AECRS), and pediatric RS. The consensus statement also touches on medical and surgical management of ARS and CRS.

Richard R. Orlandi, MD, professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, was interested to find a lack of hard evidence on common clinical practices regarding RS. “There is a paucity of evidence, and what there is, is at a low quality level,” he said. “We have things we’re dogmatic about in practice but that we’ve found little to no evidence for in the clinical literature.”

Comprehensive Guidelines

New and compiled data available within the consensus statement include the following information:

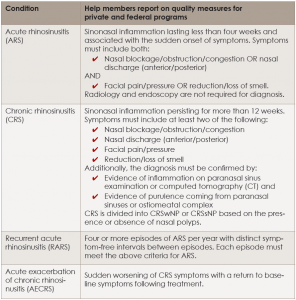

Definitions and diagnostic criteria for the different forms of RS. Statement authors have compiled adult RS definitions based on how the disease manifests itself over time. (See “Definitions and Diagnostic Criteria,” p. 8) They also identify subacute RS as a diagnosis when the condition lasts more than four weeks but fewer than 12 weeks, while cautioning that its use should be limited until it’s better understood.

Data on the societal and individual burden of RS. Statement authors found a number of interesting facts on financial costs of RS treatment and associated productivity loss:

- There was an individual direct cost of $770 to $1,220 per patient-year for CRS.

- RS-related work productivity cost approaches $4 billion annually in the United States.

- According to quality-of-life studies examined for the statement, overall CRS quality of life is worse than that of patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and Parkinson’s disease.

Review of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms and recommendations for diagnosis and treatment for RS. Focus is placed on the appropriate medical therapy at the minimum effective treatment level needed by patients. Contributing factors included anatomic variants, allergy, septal deviation, viruses, bacterial infection, biofilm, osteitis, reflux, vitamin deficiency, fungus, superantigens, innate immunity, microbiome and epithelial barrier disturbance, ciliary derangements, immunodeficiency, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Each treatment recommendation is evaluated by aggregate level of evidence, benefit, harm, cost, benefits-harm assessment, value judgments, policy level, and intervention.

We hope to better understand the heterogeneity within CRS. Previously, it was thought of as either one or two conditions, but there are far more than that. When we better define the different disease states, we can then understand the more than 20 treatments we’ve seen.—Richard R. Orlandi, MD

We hope to better understand the heterogeneity within CRS. Previously, it was thought of as either one or two conditions, but there are far more than that. When we better define the different disease states, we can then understand the more than 20 treatments we’ve seen.—Richard R. Orlandi, MDOne interesting finding was a lack of evidence showing that antibiotics are effective as a standard treatment for all forms of CRS; instead of focusing on bacterial causes, the focus in treatment recommendations is placed more on limiting inflammation. “For CRS (but not ARS), it isn’t usually an infection as much as it is inflammation, although bacteria initiating or perpetuating the condition is possible and should be considered,” said Dr. Orlandi. “This differs from traditional clinical thought—a bacterial cause has been so dogmatic that many insurance companies will not approve surgery without the patient undergoing a round of antibiotics first. Hopefully, we can cut down on antibiotic overuse, as the evidence isn’t there to support its use in many CRS cases.”

Definitions and Diagnostic Criteria for Rhinosinusitis

click for larger image

CRSsNP = CRS without nasal polyps; CRSwNP = CRS with nasal polyps.

“The emerging consensus understanding of CRS, as of 2016, is that the disorder is a phenotypic endpoint of multiple different factors that result in various forms of inflammation within the paranasal sinuses. The known potential factors include genetic predisposition, external environmental factors, imbalance of pathogenic bacteria and the normal microbiome, presence of biofilms, structural outflow tract obstruction, and a patient’s dysregulated inflammatory response, among others,” said Dr. Tabaee. “These factors may apply differently patient to patient, creating a challenge in diagnosis, especially since the inflammatory endpoint may appear similar. The common mainstays of therapy including antibiotics and steroids have a very specific role, but that’s only really one segment of treatment for these patients. Multimodality treatment in the form of medical therapy targeting underlying etiologies and the inflammatory response is combined with endoscopic sinus surgery to help restore sinonasal physiology and improve access for topical therapy; however, the specific nature of the treatment approach needs to be highly individualized based on patient specific factors.”

Evaluation of ESS effectiveness in improving quality of life. This includes an evidence-based regimen for appropriate medical therapy to pursue before considering surgery, said Dr. Orlandi, as well as intraoperative technique, and pre- and postoperative care.

Looking Ahead

Dr. Orlandi hopes that the statement’s publication will spur more questions and higher-level research. “We hope to better understand the heterogeneity within CRS,” he said. “Previously, it was thought of as either one or two conditions, but there are far more than that. When we better define the different disease states, we can then understand the more than a dozen treatments we’ve examined.”

An enhanced understanding of how different treatments work on the various RS subtypes would also help better target individual medical therapy. “Where one treatment might not work well overall, it might have great effect in a subtype,” said Dr. Orlandi. “We’ve all seen that in our practices—there will be one patient who will respond to a particular treatment when most don’t. We need to better define what treatments work best for which subtypes. It’s analogous to targeting particular cancer cells with specific chemotherapy types.”

Dr. Tabaee believes that this statement will help clinician scientists have a common dialogue about the missing areas of information ripe for scientific research. “Interestingly, the statement raises as many questions as it answers,” he says. “There are areas of recently identified pathophysiology including biofilms and genetic predisposition that do not have a clear pathway in diagnosis or treatment in the clinical work place. Further, identifying which patients will likely benefit from surgery earlier rather than later in the disease course is still a work in progress. This research statement creates a common platform for translating the current literature to clinical care considerations that are supported by scientific evidence and equally importantly highlights fundamental aspects of CRS that require further investigation.”

Amy E. Hamaker is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Methodology

Because of the deeply entrenched knowledge and practice for RS, steps were taken to safeguard against “expert opinion bias” using systematic reviews and semi-anonymous contributions and critiques. Methodology followed a five-step process:

- Each of 144 RS topics was assigned to one of 76 rhinology experts worldwide.

- Briefly, a systematic review was performed with grading of all evidence. An initial author drafted a summary of the evidence with an aggregate evidence grade and, where applicable, a structured recommendation.

- A multistage, online, semi-blinded iterative review process then refined each section.

- The section manuscripts were then combined into a cohesive single document.

- The entire manuscript was then reviewed by all authors for consensus.

For Further Reading

- Bhattacharyya N, Kepnes LJ. Patterns of care before and after the adult sinusitis clinical practice guideline. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1588–1591.

- Alt JA, Smith TL, Mace JC, Soler ZM. Sleep quality and disease severity in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2364–2370.

- Chung SD, Hung SH, Lin HC, Lin CC. Health care service utilization among patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a population-based study. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1285–1289.

- Rudmik L, Smith TL, Schlosser RJ, Hwang PH, Mace JC, Soler ZM. Productivity costs in patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2007–2012.

- Remenschneider AK, D’Amico L, Gray ST, Holbrook EH, Gliklich RE, Metson R. The EQ-5D: a new tool for studying clinical outcomes in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:7–15.