Authors of a recently issued guideline note that allergic rhinitis (AR) is estimated to affect nearly one in every six Americans and generates $2 to $5 billion in direct health expenditures annually (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152 [1 Suppl]:S1-S43). Physicians use many different diagnostic tests and treatments to manage this prevalent and costly condition, with considerable variation in results.

Explore This Issue

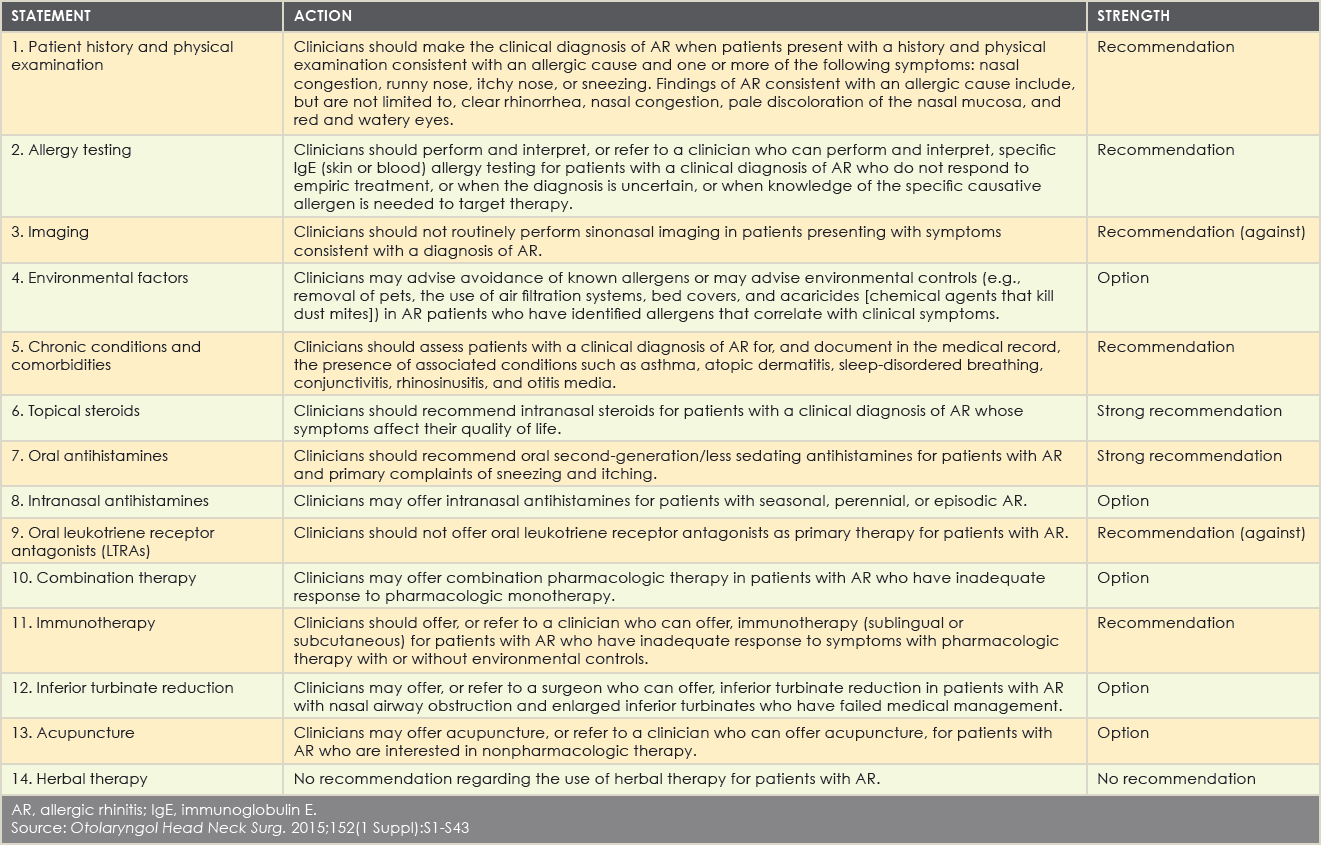

April 2015In an effort to optimize the care of patients with AR, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery organized a panel to create the guideline, “Clinical Practice Guideline: Allergic Rhinitis,” to address the most important quality improvement opportunities by evaluating the available evidence and assessing the harm-benefit balance of various diagnostic and management options. The document includes 14 recommendations that cover topics such as the value of obtaining a patient history and performing a physical examination, allergy testing and imaging, the use of environmental controls, pharmacological therapies, and alternative therapies such as acupuncture and herbal options (See “Summary of Guideline Action Statements,”).

Whit Mims, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston Salem, N.C., who served as a panel member for the guidelines, pointed out that, given the large number of studies related to AR, it’s not practical for one physician to sort through them individually. “We initially pulled 2,446 articles and identified 1,600 randomized controlled trials, which the committee combed through,” he said. “The guideline is a good way for practicing physicians to glean opportunities for better patient care that are supported by a large number of trials.” A variety of physicians who treat AR served on the panel, including representatives from the otolaryngology community, as well as family physicians, pediatricians, and physicians who practice complementary medicine. Consumer advocates also weighed in.

The guideline is applicable to both adult and pediatric patients with AR. However, children under age 2 years were excluded because AR may be different in this population than in older patients.

The Value of Patient History and Physical Examination

According to Sandra Lin, MD, an assistant chair of the panel, who is associate professor in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, one key point in the guideline is that simply conducting a careful patient history and a physical examination may be all that’s needed to make an AR clinical diagnosis and prescribe treatment. “Some physicians may think that all patients need to have specific skin or blood tests to confirm AR and proceed with treatment,” she said. “But in straightforward cases, that’s not necessary. The guideline reviews what to look for as far as specific history items and physical findings that suggest AR.”

In addition, imaging is not needed to diagnose or treat straightforward AR cases. Instead, Dr. Lin said, imaging should be reserved for patients with comorbidities or those who have another issue such as chronic sinusitis or atypical symptoms that might suggest a nasal tumor or mass.

Amber Luong, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of otorhinolaryngology at The University of Texas Medical School at Houston, who was not involved with the guideline’s creation, found these specific recommendations to be particularly noteworthy. “In straightforward cases, you should empirically treat for AR with an oral antihistamine or possibly a nasal steroid spray,” she said. “Don’t order confirmatory tests unless the patient fails empirical therapy.”

And, while it can be tempting to order a computed tomography (CT) scan, Dr. Luong said the recommendations state that it is not necessary in patients with a clear history of AR. “As a physician, it’s important to remember that a lot of AR symptoms overlap with sinus disease, but a CT scan is not warranted unless the patient doesn’t respond as expected to treatment,” she added. “Then it’s time to explore alternative diagnoses.”

Environmental Controls

The panel recommended that physicians advise that AR patients who have identified allergens that correlate with clinical symptoms avoid known allergens or possibly utilize environmental controls (e.g., remove pets and use air filtration systems, bed covers, and acaricides). The guideline includes a discussion of the literature’s findings.

“It is interesting that some of the environmental controls that reduce allergen levels don’t actually reduce symptoms,” Dr. Lin said. For example, you may recommend that a patient with pet allergies regularly wash his or her pet. “While this reduces the level of pet allergen according to the scientific evidence, it may not impact the patient’s symptoms. So why recommend something that doesn’t change a patient’s symptoms? Critically look at what the literature says and be sure to relay this to patients.”

Sarah Wise, MD, MSCR, associate professor in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Atlanta’s Emory University, who was not involved with the guideline’s creation, noted the limited amount of literature that examines the benefits of environmental controls. “Controls can be expensive and difficult for AR patients to execute,” she said. “Although there is some limited data to suggest that extensive environmental control measures may decrease allergen load and provide symptom benefit for patients with house dust mite allergy, similar evidence is lacking for many other allergens like pollen. In general, we tell pollen-allergic patients to keep their windows closed during pollen season and to change their clothes (and possibly shower) if they spend time outdoors during their allergic season, but this is based more on common sense than data.”

Pharmacological Treatments

A variety of pharmacological treatments are discussed in the guideline, with recommendations based on the patient’s symptoms and/or responses to other therapies. Dr. Lin highlighted the fact that clinicians should not offer oral leukotriene receptor antagonists as primary therapy for patients with AR. “The evidence supports more effective agents such as topical steroid sprays, oral second-generation antihistamines, and intranasal antihistamines,” she said. “This may be surprising for some physicians who use this as first-line therapy.” In patients with both asthma and AR, however, oral leukotriene receptor antagonists may be a good choice, because this therapy treats both conditions.

The guideline also advises clinicians to recommend oral second-generation/less sedating antihistamines for patients with AR whose primary complaints are sneezing and itching. “There is a knowledge gap in that most patients recognize Benadryl as the go-to antihistamine,” Dr. Mims said. “Instead, practitioners should promote the use of effective symptom-directed therapy.” According to the guideline, while oral antihistamines may not be as effective as intranasal steroids, they are adequate for many patients with mild to moderate disease and have the advantage of lower cost, rapid onset of action, and effectiveness for intermittent symptoms.

The guideline also supports the use of topical intranasal steroids for patients with a clinical diagnosis of AR whose symptoms affect their quality of life. “These medications have shown clear benefits in randomized controlled trials,” Dr. Wise said. “However, frequently patients say that a nasal steroid was ineffective. After digging deeper, we learn that the patient was not educated on its proper use. Many patients assume that nasal steroids work quickly, like topical intranasal decongestants, with symptomatic benefit in minutes. But many of these medications take hours or days to reach appropriate efficacy.”

In addition, the guideline directs clinicians toward certain combinations of pharmacologic therapy that are more effective than other combinations. “One of the common combinations of medications is an oral antihistamine and a topical nasal steroid spray, but studies haven’t shown that there is much additional benefit in taking them in combination compared to taking a nasal steroid spray alone,” Dr. Mims said. “The guideline also explains why changing to another kind of allergy medication might be a better recommendation than multiple medications in some patients.”

When medical therapy and counseling don’t effectively control symptoms, the guideline recommends referring patients to specialists for possible further testing and treatment. “This may involve a higher level of expert advice on how to best use pharmacological agents or the possible use of allergy testing and immunotherapy, which have been very effective in this population,” Dr. Mims said.

Summary of Guidance Action Statements

(click for larger image)

AR, allergic rhinitis; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Source: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(1 Suppl):S1-S43

Immunotherapy

The guidelines advise clinicians to refer patients with AR who have an inadequate response to pharmacologic therapy with or without environmental controls to a clinician who can offer immunotherapy—either sublingual or subcutaneous. The guideline is the first to discuss sublingual tablets since the FDA approved them in 2014.

“But there are other reasons to pursue immunotherapy, as it is the only treatment that will modify the underlying disease, control and prevent asthma, and prevent new allergic sensitivities,” Dr. Lin said. “Some patients and physicians may choose immunotherapy for its positive effects, such as avoiding asthma. It may also be a good choice for a child who genetically is more likely to develop AR, because it doesn’t involve an injection and can be dosed at home.” The guideline discusses some of the differences and advantages of different types of immunotherapy.

Dr. Luong pointed out that the only treatment that has a chance to change a patient’s immune response is immunotherapy. “These treatments change the immune system so patients have a less allergic response,” she said. “All of the other current first-line treatment options are symptom-based treatments.”

—Whit Mims, MD

Alternative Therapies

When a patient is interested in nonpharmacologic therapy, the guideline recommends that clinicians refer the patient to a clinician who can offer acupuncture. “Readers may find it surprising that we discuss the use of acupuncture for AR,” Dr. Lin said. “We understand that patients may want to use therapies that physicians with medical degrees in the United States don’t typically prescribe. It is important for a physician to be aware of other options when counseling patients.”

Added Dr. Mims, “Otolaryngologists might be surprised that while there is not strong evidence that acupuncture is effective for AR, there was some evidence, and the multi-specialty committee was divided upon the strength of that evidence.”

In response, Dr. Luong said, “Acupuncture is something that a physician can consider recommending to AR patients. Unfortunately, a lot of treatments are noncurative and mainly focus on symptoms. When patients are looking for nonpharmacotherapy options, this is something we can tell them to consider and research on their own.”

Philip G. Chen, MD, an assistant professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, who did not partake in the guideline’s creation, said he was pleasantly surprised to see the inclusion of acupuncture and herbal remedies. “Patients are increasingly using the Internet to find nontraditional remedies; thus, it is important that practitioners know the data regarding these options,” he said. “The updated literature regarding the potential efficacy of acupuncture is interesting. Additional research will hopefully clarify whether acupuncture or other herbal remedies are efficacious.”

While panel members looked at herbal therapies, they didn’t make any recommendations regarding their use due to limited knowledge of herbal medicines and concern about the quality of standardization and safety.

The guideline concludes with a listing of 15 areas in which more research is needed. While many of the key action statements were supported by Grade A-level evidence, review of the evidence profile for other statements revealed knowledge gaps and the need for further research.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in Pennsylvania.