Image credit: Liya Graphics/shutterstock.com

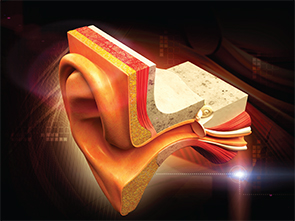

Eustachian tube dysfunction is estimated to occur as a chronic condition in approximately 4% of adults worldwide, but it is an intermittent problem in an unknown higher percentage (Clin Otolaryngol. 1992;17:317-321). The condition is multifactorial. In many cases, inflammation of the mucous membranes in and around the Eustachian tube produces obstruction. Uncoordinated movement of the muscles that open and close the tube may also play a role. Extrinsic factors such as excessive lymphoid tissue around the Eustachian tube opening may also be seen. If chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction remains untreated, it can lead to cholesteatoma and hearing loss.

Explore This Issue

January 2016Initial treatment targets the potential causes of mucosal inflammation, such as allergic rhinitis and acid reflux. This often includes topical or oral steroids, antihistamines, and acid-suppressant medications. “However, none of these have proven to be reliably effective,” said Edward McCoul, MD, MPH, director of rhinology and sinus surgery at Ochsner Clinic and Health System in New Orleans, La.

The indications for surgery are still being determined, and research is ongoing. Surgery may be appropriate for patients with chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction that is moderately severe and disrupts daily function or in the presence of chronic middle ear fluid that produces hearing loss.

For many years, tympanostomy tubes were the only available treatment. “Although generally quite safe, this invasive procedure has the potential to produce sequelae, including tympanic membrane perforation, scarring, and hearing loss,” Dr. McCoul said. “Previous generations of otolaryngologists practiced catheterization and irrigation of the Eustachian tube, but this was eventually abandoned due to ineffectiveness.”

But three coinciding advancements have enabled treatment of the relatively large number of patients who suffer from Eustachian tube dysfunction with a procedure that uses a balloon to dilate the Eustachian tube, said Ralph Metson, MD, professor of otology and laryngology at Harvard Medical School and director of the rhinology fellowship program at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston. These advancements include a new theory about the pathophysiology of Eustachian tube dysfunction (i.e., that the nasopharyngeal end of the Eustachian tube, not the more proximal bony segment, is the site of obstruction); new endoscopic equipment for better visualization to diagnose the problem; and new tools for enlarging the Eustachian tube opening (initially lasers and microdebriders, now balloons).

In addition, a diagnostic tool that reliably identifies and measures Eustachian tube dysfunction—the Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire (ETDQ-7)—is now available (Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1137-1141). “A clinician can use the short, validated symptom score to both identify Eustachian tube dysfunction and assess the response to treatment in adult patients,” said Dr. McCoul, one of the tool’s developers and co-author of a paper about the assessment tool.