The first time Gayle Woodson, MD, went on an international otolaryngology outreach mission 15 years ago, she was “a little afraid to go.” The chair of otolaryngology at Southern Illinois University in Springfield was traveling to Tanzania, a country prone to violence and war, and there was no telling what kind of environment she was entering.

Dr. Woodson still recalls what an impression the experience made on her. “I was always thinking I wanted to give back. On my first trip to El Salvador, we had armed guards at all times. Over time it was a lot safer, and it was incredible to see the changes in the people—standing up straight, and looking us in the eye with dignity,” she said.

Dr. Woodson is one of approximately 10 to 15 percent of the 9,000 members of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) who, according to Catherine Lincoln, CAE, MA, senior manager of the Academy’s International/Humanitarian Affairs Committee, participate in international medical missions. Volunteers include practicing otolaryngologists, residents and retirees, she said. But while doctors say such trips are intrinsically rewarding, how can they know the missions are measurably successful?

Several groups are in the process of establishing approaches to measure the effectiveness of their programs. James E. Saunders, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and chair of the AAO-HNS Humanitarian Efforts Committee, said the movement might be a result of a generational shift in humanitarian service.

“More and more younger individuals [are getting] involved and asking the harder questions about the larger picture of what we offer, thinking about things like public health issues that impact on the diseases we treat…and also an increasing interest in research that is related to international medicine, whether on the causes of disease, the resources available or the outcomes of such work,” he said.

Evidence-Based Missions

The AAO-HNS Humanitarian Efforts Committee recently appointed a group within the committee to look at best practices, reasonable outcomes and ethics abroad. According to Dr. Saunders, the group met in October to discuss these issues, and plans to draft a post-trip action survey to assess the effectiveness of their techniques abroad, such as training local doctors and involving them in the administration of treatment.

“I think our goal as a committee will be more of saying, ‘This is what I think you should strive for, these are the kinds of things that are best practices,’ and part of best practice should be evaluating outcomes, no question,” he said.

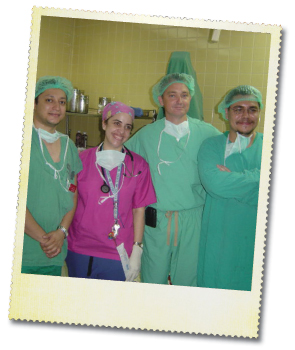

Operation Smile, an organization that provides reconstructive surgery for children and young adults born with cleft lip, cleft palate and other facial deformities, hosted a summit in Norfolk, Va. in September as part of a periodic evaluation of its Global Standards of Care program, an initiative started in 2006 that is aimed at maintaining and implementing the best evidence-based practices on international missions. The summit, according to Ruben Ayala, MD, medical officer of Operation Smile, focused on ways missions can be improved, and how the organization can hold these missions to the highest standards of care.

“There is a sense that if we commit our leaders to meaningful discussions, that is, for everybody to agree to commit to the best possible care that we’re going to fill worldwide, then it is a lot easier to execute,” Dr. Ayala said. He added that the most tangible measures are post-op results.

“The reality is that you have to look at evidence-based medicine and use it as your benchmark—and do everything in your power to get to that benchmark,” he said.

According to the organization’s 2010 Annual Report, between July 1, 2008 and June 30, 2009, Operation Smile volunteers travelled to 22 countries, providing free surgical treatment for 12,993 children and young adults, which resulted in 12,993 documented successful surgeries. Public Relations Director Jessica Kraft said that all Operation Smile surgeries are evaluated internally by a medical oversight board, and the group relies on data collected in the field to help it evaluate procedures. Kraft said that while follow-up is encouraged for every patient, there are some mission sites in rural areas where the percentage of patients who return for the 6-month follow-up are low, whereas more populated areas have a follow-up rate of around 70 percent.

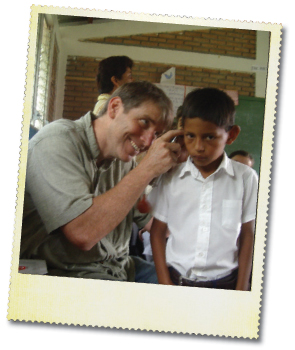

Drew Horlbeck, MD, director of pediatric otolaryngology at Nemours Children’s Clinic in Orlando and Jacksonville, Fla., attends at least one mission each year in South and Central America. While he has been participating in international medical missions for over 20 years, it wasn’t until 2009 that he decided to study the results of some of his missions.

“The question was always, ‘I want to follow up on who we did last year. [The local doctors] say everybody’s great, but are they really doing fine?’” he said.

Dr. Horlbeck and colleagues analyzed data from three otologic surgical missions conducted in Paraguay and Honduras from 2003 to 2006 (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(4):559-65). During these missions, surgeons from Wilford Hall Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas aimed to treat chronic ear infection with a single surgery. Researchers reviewed data from 117 patients who underwent tympanoplasty, canal wall up mastoidectomy or canal wall down mastoidectomy. Follow-up records were available for 77 patients. The percentages of patients who experienced success with tympanoplasty, canal wall up and canal wall down were 14 (63.6 percent), 21 (70.0 percent) and 23 (92.0 percent), respectively. The authors concluded that the results fall within those expected in developed nations.

According to the authors, “the ability to return to the same location and limiting the scope of the mission to ear disease gave the unique opportunity to collect data, evaluate results, and quantify patient benefits.”

Follow-up and Training

While programs are beginning to quantify their missions abroad using data analysis, some missions continue to measure their successes through individual patient follow-up and local doctor training.

“Many of us have long-standing relationships with providers in local countries, and so we get feedback on our patients there as well as here. It’s not a whole lot different than how we measure outcomes here at home, which is to say we don’t,” said Dr. Saunders, whose Mayflower Medical Outreach program runs trips to Nicaragua about twice a year.

Dr. Saunders said the rate of success is much higher abroad when the procedure has been proven successful in the U.S. “The greatest need and the thing we’re focused on is ear surgery,” he said. “Ear disease is the most rampant untreated part of otolaryngology in that part of the world, and also pretty much true around the world. It’s fortunate for me because that’s where my expertise is. What they needed is what I had to offer.”

Procedures like cochlear implants, according to Dr. Saunders, are more difficult to do on missions, although the need is there. “Those are highly technical procedures with the need for a tremendous amount of peripheral support, and clearly that’s a place where you have to have that kind of long-term relationship and really have some good outcome measures,” he said.

Dr. Horlbeck said volunteers should avoid procedures that require ICU stays.

And, according to a recent editorial in the World Journal of Surgery about the “sins” of humanitarian work, “One good rule is to offer the types of procedures that are minimally invasive, to relieve immediate discomfort, and that require little follow-up care, especially for missions that are short-term” (World J Surg. 2010 34(3):466-470).

For Dr. Woodson, training local physicians is the “major outcome variable” of her missions abroad. Twice a year, Dr. Woodson travels to Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre in Moshi, Tanzania, where she and other otolaryngologists and audiologists treat a variety of problems, including meningocele, laryngeal cancer, papilloma, parotid tumors, tracheal and glottic stenosis and laryngeal paralysis. “When we went to Tanzania, people were dying from laryngeal cancer, who could have been cured by laryngectomy. We resolved to teach the local doctors how to take care of these people,” she said.

Dr. Woodson and her husband, Tom Robbins, MD, an otolaryngologist and director of the Simmons Cancer Institute at Southern Illinois University in Springfield, have been bringing medical students back to the U.S., sponsoring their studies at her teaching hospital in Illinois. Dr. Woodson and Southern Illinois University have hosted three medical students, an otolaryngologist, and two nurses for visits of one or two months. On a typical mission, Dr. Woodson and her team will see about 50 patients on the first day and select patients for surgery for the next four to seven days, with the number of patients varying with the complexity of the surgery. While local physicians provide most of the follow-up, the team will usually see the patients six months later, when they return to Tanzania.

Dr. Woodson said she recognizes the importance of metrics and hopes to be able to do this type of research once the program has graduated out of its early stages. “Metrics would be valuable, because we need to know if what we are doing has a positive impact, and what we could do better,” she said. “Outcome data will also be important for raising money if we establish a foundation, and for giving information to other physicians who might be interested in coming here.”

Challenges

One major challenge for physicians attempting to establish metrical results for humanitarian missions is that they vary greatly not only by mission location, but by resources as well, Dr. Saunders said.

“If you try to set up that everyone needs to get 80 percent or 90 percent success, you shouldn’t be doing it…It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be looking at numbers and success rates, but it’s hard to come up with one set of outcome measures and outcome levels that fit all of the different environments we work in,” he said.

Dr. Saunders said expectations abroad versus those that must be met within the U.S. differ greatly because standards of care have yet to reach an equivalent plane. “My primary goal in Nicaragua is to get through an operation safely and have a dry ear,” he said. “We will try to get them as much hearing restoration as possible, but in the U.S., because our standards are higher, we focus more on hearing reconstruction, because the other things are taken for granted.”

Dr. Horlbeck said an increased focus on local training will probably have the greatest effect in the long run. “Ultimately, the goal would be to make yourself obsolete,” Dr. Horlbeck said. “You don’t want to provide a country their health care if you can teach them how to do it. You can show them what’s possible and have them keep it going on their own. That’s the goal.”

Leave a Reply