For decades, otolaryngologists have been frustrated by the refusal of some patients with hearing loss to use hearing aids. Statistics on noncompliance vary, but there is general agreement that only about 20 percent to 25 percent of Americans with treatable hearing loss use hearing aids (Hear Rev. 2009;16(11):12-31). The problem seems to be more acute for people with mild hearing loss: A consumer survey conducted by the nonprofit Better Hearing Institute in 2009 found that fewer than 10 percent of people with mild hearing loss use amplification and that even among people with moderate-to-severe hearing loss, only four in 10 use amplification (Hear Rev. 2010;17(6):12,14-16).

Non-users offer many reasons for going unaided, including the high cost of hearing aids, the inconvenience of wearing them, the fear of seeming old, and negative reports from friends and family who have tried them. But an emerging category of hearing devices, middle ear implants (MEIs), may offer a solution to the noncompliance problem, experts say.

“If you have a patient whose hearing is not bad enough for a cochlear implant but who is really dissatisfied with hearing aids, that is a niche for implantable devices,” said Moisés A. Arriaga, MD, MBA, FACS, who has participated in clinical trials of several models of MEIs. Dr. Arriaga is professor of otolaryngology and neurosurgery at Louisiana State University and director of Our Lady of the Lake Hearing and Balance Center in Baton Rouge, La.

Options

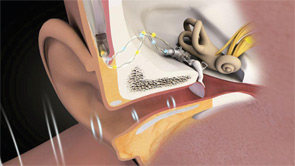

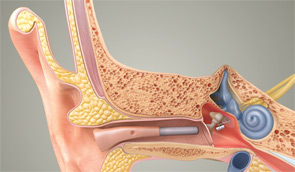

Patients can choose between partially implantable and totally implantable systems. In the former, the receiver is implanted on the ossicular chain, while the microphone, battery and, in some cases, the processor are external. In the latter, every component is surgically implanted except for a remote control that lets the wearer adjust the volume and turn the device on and off.

Currently, three companies have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved middle ear implants: MED-EL, an Austria-based company that in 2003 purchased the Vibrant Soundbridge technology from Symphonix; Ototronix, which makes the Maxum System, a device based on SOUNDTEC Inc.’s FDA-approved Direct System; and Envoy Medical Corp., of Minneapolis, which received FDA clearance for its totally implantable Esteem system in March 2010. A fourth company, Otologics, has both semi-implantable and totally implantable systems on the market in Europe, but neither has been approved in the U.S.

While today’s MEI systems vary in many respects, they all involve the implantation of a transducer on or near the incudostapedial joint of the ossicular chain. That implantation allows the system to drive the middle ear directly rather than doing so by sending an amplified acoustic signal through the ear canal, as conventional devices do.

Although Otologics LLC, based in Boulder, Colo., began with and still makes the partially implantable MET (middle ear transducer), CEO Jose Bedoya likened the evolution of MEIs to that of other medical implants. “They all start as external devices and then evolve to be implanted. The hurdle is the technology required to internalize them,” he said.

Until Envoy Medical’s Esteem product received FDA clearance in March 2010, every MEI made or marketed in the U.S. was electromagnetic. These devices contain an implanted magnet and an external coil coupled to the microphone. When the coil is energized by a signal, it causes the magnet to vibrate and move the ossicles.

The Esteem, on the other hand, uses piezoelectric technology. The mechanical signal is detected from a piezoelectric transducer at the head of the incus (the sensor) and converted to an electrical signal, which is then amplified, filtered and converted back to a vibratory signal that moves the ossicles.

Lifestyle Advantages

The conventional air-conduction approach, said Bedoya, is an inefficient way of transmitting sound. Bedoya, whose company has developed two implantable systems, said that the thinking behind the MEI was, “Let’s see if surgically we can drive the middle ear directly and eliminate those inefficiencies and potential distortions.”

Once the device is successfully implanted and programmed, the wearer can essentially ignore it. “There is something very appealing to patients about not having to put something on to be able to hear,” Dr. Arriaga said. “They can leave it on 24 hours a day, swim or shower with it, and never worry about forgetting or losing it.”

Because it’s totally implanted, there is no issue of stigma or cosmetics. Maintenance is also minimal, with an implanted battery the manufacturer says will last for 4.5 to nine years.

“With a regular hearing aid, you take sound, you convert it into electricity, you manipulate it, and then you convert it back to sound, so there are two conversions,” Dr. Arriaga explained. “With an implantable device, you are taking sound, converting it to electrical energy, but you aren’t converting it back to sound. You’re leaving it as electrical energy that is moving the ossicular chain.”

The advantage of this approach, he said, is more clarity than that achieved with traditional hearing aids.

“Because of the direct movement of the ossicular chain, you don’t have the feedback issues, which is one of the key benefits over hearing aids,” said James Douglas Green, Jr., MD, FACS, founder and president of the Jacksonville Hearing and Balance Institute in Jacksonville, Fla., who has been working with MEIs for nearly 20 years. “You get great clarity and you get gain in some ways that you can’t get with other systems.”

Carl Geisz, sales manager at Envoy, said one advantage of the Esteem’s design is that it uses the patient’s eardrum as the microphone, letting the system take full advantage of the natural acoustics of the outer ear and, therefore, delivering a more natural sound.

Four Iranian scientists recently published the results of a clinical trial of Envoy Medical’s Esteem middle ear system in an article in European Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, which appeared online on Feb. 17. Lead author Faramarz Memari, MD, who is on the faculty of the department of otorhinolaryngology at the University of Medical Sciences and Health Services in Tehran, noted that while the 10 subjects experienced gain similar to that experienced with their own conventional aids, they reported better subjective hearing quality.

“Some patients who did not have better thresholds in their post-op audiogram compared with their hearing aids were still very happy,” he said in an interview with ENT Today. “One patient stated that he hated washing dishes while using conventional hearing aids, because the sound of dishes bothered him. But now he enjoys washing dishes because that sound doesn’t bother him and instead he can hear the sound of water running very well.”

Representatives of other companies, however, contend that middle ear systems with digital processors (Esteem uses an analog processor, for example) can simply use processing to substitute for the benefit of natural pinna and ear canal effects.

Darla Franz, director of education and corporate communications at MED-EL, said that the target market for her company’s Vibrant Soundbridge system consists largely of “people who either are medically unable to wear a hearing aid, or who have tried a lot of hearing aids and spent a lot of money and for whatever reason are never able to achieve adequate benefit. They have reached the end of their tolerance with traditional treatment.”

Michael Spearman, CEO of Houston-based product developer Ototronix, cited issues that may drive people with more severe losses to consider switching from conventional hearing aids with acoustic speakers to middle ear devices like his company’s Maxum System. Because of their degree of hearing loss, he explained, these patients need more amplification, especially in the high frequencies, than those with milder losses. Their more powerful hearing aids need to be fitted with custom earmolds, which occlude the ear canal. The resulting occlusion effect often causes wearers to complain about the unnatural quality of the amplified sound, especially for their own voices.

Many of these patients also complain of feedback, which can occur when amplified sound leaks back into the ear canal through the hearing aid vent and is re-amplified. The squawking and whistling of hearing aid feedback is annoying both to wearers and to those around them. Also, stopping feedback may require reducing the amount of amplification, which can leave wearers with less sound than they need.

Obstacles

In view of favorable reports from MEI users, why are only a few thousand of these devices in use worldwide? One reason could be that until recently, only the Vibrant Soundbridge, which was approved by the FDA for adults in 2001, was available in this country. The cost and the need for surgery could be other reasons.

Cost and the nature of the implant surgery differ greatly among the various brands. On the low end of the price range is the Maxum, which Ototronix CEO Spearman said typically costs about $9,000 for both the device and the implantation procedure. The company designed the implant to make the surgery “minimally invasive,” he said. It takes about 30 minutes and can be done transcanal under a local anesthetic in the procedure room of a medical office. As with all MEIs, the surgery is performed by an otologist, but, said Spearman, little special training is required.

Because of the direct movement of the ossicular chain, you don’t have the feedback issues, which is one of the key benefits over hearing aids.

Because of the direct movement of the ossicular chain, you don’t have the feedback issues, which is one of the key benefits over hearing aids.

—J. Douglas Green Jr., MD, FACS

On the other end of the spectrum is the Esteem, which costs $30,000 and takes about 2.5 to three hours to implant, according to Geisz. He added that otologists must undergo an intensive training program before being permitted to do the surgery.

When the fully implantable Otologics Carina reaches the American market, CEO Bedoya estimated it will cost about $15,000, based on the company’s experience in Europe. Currently, implantation takes about 90 minutes, but the goal is to reduce this time to an hour.

MED-EL does not publish an estimated price for its Vibrant Soundbridge, in part, Franz said, because the cost of the surgery depends on the hospital. However, she said, Soundbridge is “in the same ballpark” as other MEIs and “much more expensive than a hearing aid.” Typically, the price of a pair of high-end hearing aids falls in the range of $5,000-$6,000.

As for the surgery, MED-EL provides some support training, but, Franz added, “It’s not a big stretch from what otologists already do. It’s similar to cochlear implant surgery.”

In the end, some of those interviewed believe that reimbursement will determine whether the MEI remains a niche product or goes mainstream. Currently, Medicare and most insurance companies in the U.S. do not cover either the device or the surgery. As a result, said Dr. Green, “The price-to-benefit ratio is outside the range of what most people can afford, so it really limits it to people who are wealthy. With the economy where it is, the average person doesn’t have the disposable income to pay for these.”

However, he added, “If it were covered by insurance, I think you’d have people lined up outside the clinics.”

Other factors may also be at play. One of these, said MED-EL’s Franz, is “lack of awareness that the technology is available.” While she thinks that otologists are generally knowledgeable about the devices, she sees a pressing need to get more information out to consumers and also to audiologists so that they will consider it as an option for their unsuccessful hearing aid patients.

Marshall Chasin, AuD, MSc, has frequently written about middle ear implants. Dr. Chasin, an audiologist who serves as coordinator of research at the Canadian Hearing Society in Toronto, sees a logistical problem standing in the way of maximum use of MEIs. Because of the complementary roles of the surgeon who implants the device and the audiologist who programs it, he noted, “there needs to be a well-defined interaction between the otolaryngologist and the audiologist. However, this is not always the case.”

Some Reservations

Despite the obvious attractions of a totally implantable system, some observers express reservations. Dr. Green noted that the concerns he has about MEIs in general—including their high cost, the possible need for repeated surgical procedures, and the risk of implanting someone whose hearing loss soon becomes too severe to he helped—are even more troubling with totally implantable devices, because the surgery is more complicated. Also, he noted, with the Esteem, replacing the battery requires additional surgery from time to time.

We’ve reached a time when implantable devices have a real role as part of the spectrum.

We’ve reached a time when implantable devices have a real role as part of the spectrum.

—Moises Arriaga, MD

“The fully implantable is a seductive direction to go,” said Franz, who noted that her company is developing such a system. She also pointed to the advantages of partial implantation. For example, when MED-EL introduced Amadé, a new digital external processor, in the U.S. last year, existing Vibrant Soundbridge patients could easily substitute it for their old processor without the need for surgery.

“MED-EL’s philosophy is to take an atraumatic approach,” Franz said. Soundbridge surgery does no damage to the middle ear and has no impact on residual hearing.” She contrasted that with implantation of the Esteem, which involves removal of a small part of the incus. (Envoy Medicals counters this statement by pointing out that the incus can be easily reconstructed should a patient quit wearing the device.)

Another limitation of currently approved totally implantable systems, she said, is that only people with purely sensorineural losses are candidates. However, she noted, MED-EL is conducting investigational trials on an implantation method for the Soundbridge designed to help patients with conductive or mixed losses. It involves coupling the device to the round window, which causes the bone of the outer wall of the cochlea to vibrate.

Despite the challenges facing middle ear implants, otologists and manufacturers alike generally anticipate a dramatic increase in the adoption of this still-new category of device.

“We’ve reached a time when implantable devices have a real role as part of the spectrum of treatments available to people with moderate to severe hearing loss,” said Dr. Arriaga. He estimated a potential U.S. market for MEIs in the high six figures.

“We just have to let people know it’s there,” he added. “Right now, a lot of people think there is nothing [that] can be done beyond hearing aids, and that’s not necessarily the case.”

Leave a Reply