A clearer picture of reimbursement for otolaryngology procedures nationwide has emerged over nearly the past decade, with public access to claims data detailing use by physicians who care for Medicare beneficiaries now permitted since 2014 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (N Engl J Med. 2014;371:99–101). While access to information on private payers isn’t available, having access to Medicare claims data offers a useful dataset to critically assess trends in reimbursement over time.

A clearer picture of reimbursement for otolaryngology procedures nationwide has emerged over nearly the past decade, with public access to claims data detailing use by physicians who care for Medicare beneficiaries now permitted since 2014 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (N Engl J Med. 2014;371:99–101). While access to information on private payers isn’t available, having access to Medicare claims data offers a useful dataset to critically assess trends in reimbursement over time.

Otolaryngologists are taking advantage of the data to gain insight into medical claims submitted to Medicare for otolaryngology procedures, with a number of studies published over the past five years detailing reimbursement trends over time for procedures performed in different settings, variations in reimbursement, compensation for the most common procedures, and other data points. The studies illuminate the underside of data previously published showing that reimbursement for otolaryngology services is generally below the federal benchmark (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:929–938).

Lessons from the Data

Among the findings are data showing that otolaryngologists receive less compensation for the most common procedures performed. A study examining Medicare reimbursement trends for otolaryngology procedures performed between 2000 and 2019 found that the average reimbursement for the 20 most commonly billed procedures decreased by 37.63% between these years after adjusting for inflation. Stereotaxis procedures on the skull, meninges, and brain (CPT code 61782) had the greatest mean decrease in reimbursement at 59.96%, and septoplasty (CPT code 30520) had the smallest decrease at 1.5% (Laryngoscope. 2021;131:496–501). Similarly, a study looking only at otology procedures found that the total average reimbursement for all otologic procedures decreased by 21.2% from 2000 to 2020 (with an average yearly decrease of 1.3%) after adjusting for inflation (Otol Neurotol. 2021;42:505–509).

Referring physicians will care a lot about how we manage our fee-for-service patients because that will directly impact the salary of those who refer to us. — Willard C. Harrill, MD

Other studies show wide variations in compensation for different procedures. One study found that total compensation rates for pediatric procedures varied up to three-fold (i.e., drainage of deep neck abscess vs. frontal sinus surgery) and intraservice (incision-to-closure) rates varied up to 150-fold (i.e., thyroglossal duct cyst excision vs. pediatric tracheostomy) (Laryngoscope. 2023;133:1739–1744).

One message from these studies is the need to understand how the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) process valuation of otolaryngology procedures for Medicare beneficiaries, a process predicated on sufficient evidence for a procedure to meet the criteria for a reimbursement code as determined by the American Medical Association (AMA). Novel procedures may be stuck in limbo—showing efficacy in the clinic but not able to generate enough evidence to meet the code criteria. Without a code, new procedures and technologies can’t move onto valuation and are commonly thought of as experimental or investigational by commercial payers and are therefore not covered.

Otolaryngologists are critical agents in this process. On the front end of the valuation process of a new procedure is input from the experts who use it. On the back end, once a valuation is made in the current payment fee-for-service (FFS) model, otolaryngologists no longer have much input into compensation issues. Below is a description of what transpires in between.

Determining Compensation: Fee-for-Service Model

R. Peter Manes, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology in the department of surgery at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., explained that valuation by Medicare for a new procedure or technology begins once the AMA deems there’s enough evidence to justify a new CPT code. Organizations like the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) will send out surveys to members who perform the procedures to get input on clinical aspects of the procedure: How long does it take? What is its complexity? Where does it fall within the existing reimbursement system?

The data collected is then sent to a committee made up of representatives from 31 specialties who review the information, get feedback from advisors to the society that conducts the survey, and, based on that information, come up with a relative value unit (RVU) for the procedure. This information is all passed on to CMS, which makes the final determination of what the RVUs will be for that procedure, to include the work RVU and practice expense RVU (e.g., equipment/staff time required), along with a professional liability component. Once all that is done, the actual reimbursement by Medicare depends on that RVU and how much of that Medicare will reimburse.

As described, data submitted on the surveys by members of an organization, such as AAO-HNS, is foundational for the eventual development of RVUs. Physicians, therefore, are key players in this process. “Individual physicians play an important role in reimbursement by completing surveys,” said Dr. Manes. “I always encourage practitioners to complete surveys to the best of their ability.”

Dr. Manes also underscored the fact that members/physicians play a key role in communicating with the academy about reimbursement issues. “Not all things can be fixed,” he said, “but if we don’t know what’s going on, we can’t do anything.”

Current Reimbursement Issues

An ongoing reimbursement issue, or troubled point, as Dr. Manes calls it, is getting coverage for a new procedure or technology. As described, setting a CPT code for a new procedure or technology requires meeting certain criteria, some of which can be hard to establish given the dearth of data (too few studies or those that are too small to show efficacy) or because the criterion is vague (e.g., the procedure must have “widespread” use).

“Some new procedures we find are helpful to patients, but they haven’t met the criteria yet, so they aren’t covered,” said Dr. Manes. “It’s a real challenge.”

Dr. Manes refers to these procedures/technologies as being in a “gray zone”—showing efficacy in the clinic but not meeting criteria for a CPT code. “In this case, Medicare doesn’t provide a code, so many other insurers won’t cover them because there’s no code,” he said.

He cited two new procedures for rhinitis that recently moved from the gray zone to receiving a code and valuation: the application of either radiofrequency or cryotherapy to the posterior nasal nerve to control the condition. Both procedures had decent studies showing they worked, but the data needed to be consolidated to meet the criteria for a code, which it finally was. The codes will be available in 2024.

Although this can help with one problem, it can also open up another issue. Even though Medicare will cover a procedure once it has gone through the valuation process, other private insurers may still call the procedure experimental or investigational. This frequently happens with new otolaryngology procedures, according to Dr. Manes.

What’s needed is good data showing that the procedure is both effective and potentially cost effective for the payer, said Dr. Manes. Another good resource to push for coverage is patient testimonials. “When patients advocate for treatment for themselves, payers may listen,” he said.

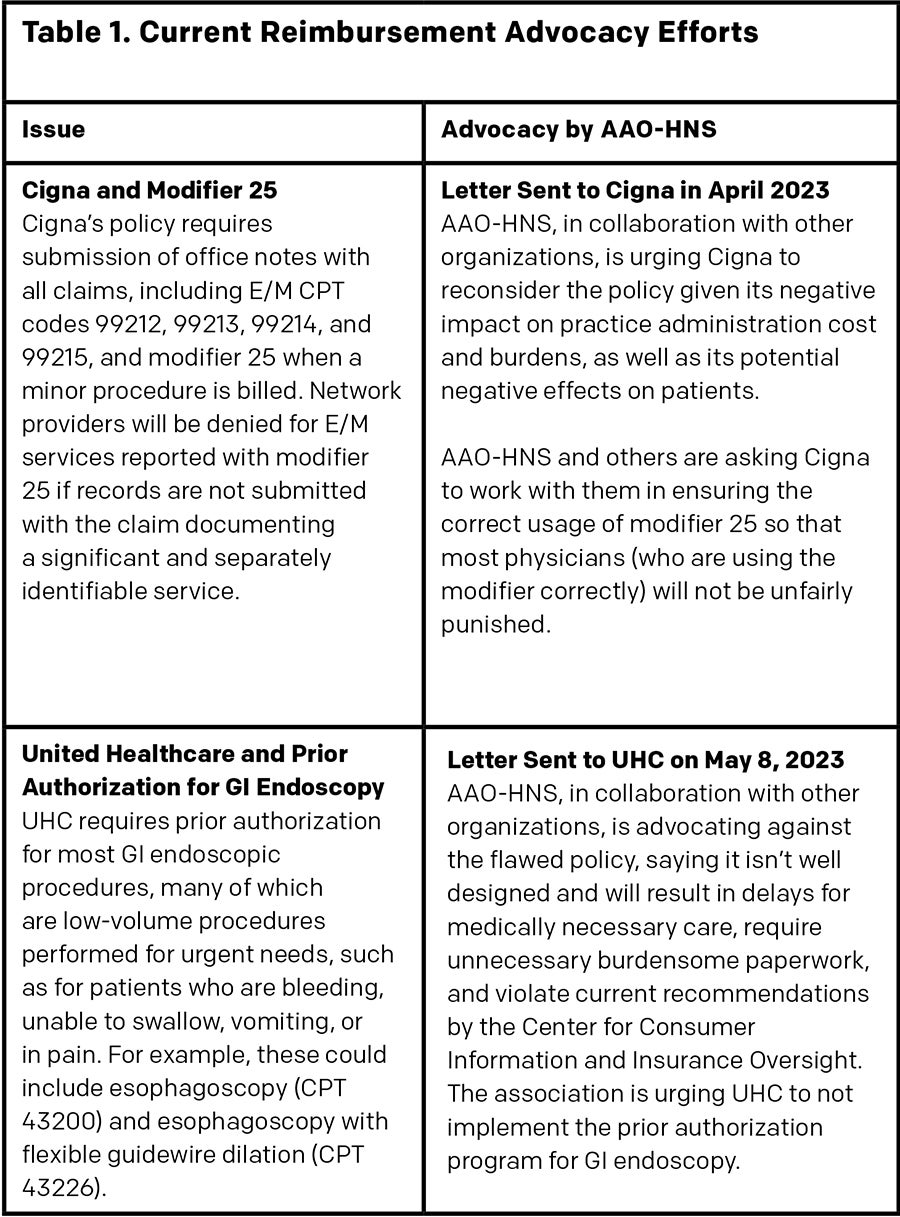

Along with these ongoing reimbursement issues, a number of other issues are currently under discussion. Most recently, the AAO-HNS, in collaboration with the American Academy for Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS), successfully changed a policy by United Healthcare (UHC) that required performing septoplasty (CPT 30520) and nasal valve surgery (CPT 30465) in a staged fashion instead of concomitantly. The policy denied coverage of both procedures if they were done together. The AAO-HNS and AAFPRS successfully argued that requiring two separate surgeries and use of septal cartilage for nasal valve reconstruction was detrimental to patient care. On June 1, 2023, UHC updated its coverage to again permit and cover the concomitant performance of these two procedures.

“Why an insurance company would deny the two together is unclear,” said Stephen S. Park, MD, the G. Slaughter Fitz-Hugh Professor and Chair and director of the division of facial plastic surgery at the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville. “It makes absolute sense that the two should be covered independently as they are two different procedures performed to improve nasal function and aren’t mutually exclusive.”

Samuel L. Oyer, MD, an associate professor of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at UVA Health, also underscored the fact that septoplasty and nasal valve repair are two distinct clinical entities with independent treatments. “There are no data supporting the exclusion of concurrent septoplasty and nasal valve repair,” he said. “In fact, there are several studies supporting these procedures concurrently to maximize patient improvement and minimize morbidity of a second surgery, such as a recent clinical practice guideline from the AAO-HNS.”

Dr. Oyer raised another reimbursement issue that he and other facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons are facing: coverage for facial feminization procedures, including rhinoplasty, as part of gender-affirming care. He said several plans cover gender-affirming genital and chest surgery but specifically deny facial surgery because it’s considered cosmetic. Results of a 2021 study bear this out: Of 150 insurance policies from top commercial health plans nationwide, only 27 (18%) held favorable policies for facial feminization surgeries (Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2021;23:270–277). The procedure covered most by the favorable policies was chondrolaryngoplasty.

“The rationale behind approving only a portion of the necessary surgical care for an approved condition, gender dysphoria, isn’t clear,” Dr. Oyer said. “This can create a lot of patient angst, as they’re already struggling with numerous healthcare and social inequalities.” Dr. Oyer noted that the current guidelines by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health support the benefits of gender-affirming facial surgery (Int. J. Transgender Health. 2022;23;S1–S260) (See Table 1 for additional current AAO-HNS advocacy for better coverage).

Future Reimbursement Issues

Reimbursement issues going forward may be less about wrangling with payers about coverage denials and prior authorization and more about a shared risk dialogue with payers and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) on costs and benchmarks of care.

“The problem with FFS is that we’re never fully aware of what drives a payer’s decision,” said Willard C. Harrill, MD, an otolaryngologist with Carolina Ear Nose & Throat, Sinus and Allergy Center, PA, in Hickory, N.C., and adjunct assistant professor of otolaryngology at Atrium/Wake Forest Baptist Health and the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill. “There’s usually little initial transparency available to physicians about what’s triggering a policy change.”

Dr. Harrill, who is a member of the AAO-HNS Physician Payment Policy committee, explained that physicians like otolaryngologists focus daily on efficiently providing quality care for their patients. “When a payer’s giving us a hard time on reimbursement, it’s usually because of cost trends, which we as physicians have no awareness of or access to,” said Dr. Harrill. “In FFS, we’re disconnected from the total cost-of-care picture of what we’re doing as well as of who and where we’re engaging within that care process.”

What can provide that needed transparency, he said, is engagement with alternative payment models (APMs) that allow, and may mandate, that physicians have a seat at the table in helping to determine cost-of-care management and meaningful outcomes measures. “In the future, physicians will have full price transparency as value-based payment models begin to drive payer policy decision,” he said. “The ability to play a role in managing the cost curve within high-quality care is how to get a seat at the reimbursement policy table.” This is critical within the value-based care (VBC) APM.

Simply put, VBC is a way to engage payers and physicians in shared decision making about the cost of care and the metrics on which physicians will be measured to deliver that high-quality care within a lower total spend. The shared dialogue begins with the assumption that, for example, a procedure is efficacious within a care pathway. Reimbursement then depends on physicians and payers agreeing to the total cost of care within a defined episode of care. Physicians assume both upside and downside risk, meaning that they share in the savings when the total cost of care delivered is lower than agreed upon, and they share in the deficit when they spend more than agreed upon. Dr. Harrill emphasized that, to function properly, this system requires total transparency of cost among stakeholders. It also removes the need for prior authorization completely.

Simply put, VBC is a way to engage payers and physicians in shared decision making about the cost of care and the metrics on which physicians will be measured to deliver that high-quality care within a lower total spend. The shared dialogue begins with the assumption that, for example, a procedure is efficacious within a care pathway. Reimbursement then depends on physicians and payers agreeing to the total cost of care within a defined episode of care. Physicians assume both upside and downside risk, meaning that they share in the savings when the total cost of care delivered is lower than agreed upon, and they share in the deficit when they spend more than agreed upon. Dr. Harrill emphasized that, to function properly, this system requires total transparency of cost among stakeholders. It also removes the need for prior authorization completely.

The rationale behind approving only a portion of the necessary surgical care for an approved condition isn’t clear. — Samuel L. Oyer, MD

“In value-based care, it’s mandatory that we as physicians are part of these conversations both on the cost side as well as on the spend side, so we need access to the total cost-of-care data we’re being tied to and judged by,” said Dr. Harrill. He also said it’s mandatory that physicians drive the discussion on the quality benchmarks they’ll be judged by and ensure that accurate disease severity and patient comorbid health risks are factored into cost benchmarks.

Although otolaryngology hasn’t been forced to move to VBC, a shift from FFS to VBC is happening throughout the healthcare system from its initial implementation in primary care after the 2010 Affordable Care Act and the 2015 MACRA legislation. More specialists are engaging with VBC, including cardiology, orthopedics, nephrology, and oncology; it’s rapidly moving toward implementation in general surgery, gastroenterology, and pulmonology.

Dr. Harrill believes that it’s in otolaryngology’s best interest to learn about the process to ensure that the specialty has the necessary infrastructure to operate in this shifting payment landscape. He underscored the fact that APMs such as VBC are a complex, data-driven business model requiring new learned skills and analytics to succeed.

In 2026, CMS will roll out new patient episodic care models. Whether or not otolaryngology will be a part of that is unknown at this time. Despite CMS’s decision, however, otolaryngology will face increasing challenges in reimbursement and coverage within an FFS payment model in an environment in which primary care and other specialties are implementing an APM. Specialist referrals will begin to track toward what the system views as high-value specialists.

That said, Dr. Harrill said that it takes years to transition from FFS to APM, and that he doesn’t see otolaryngology FFS payments being less than 70% of the revenue streams in the next seven years. “It’s inevitable that otolaryngology will engage in value-based care,” he said. “We’ll never be over 30% APM based on the total cost-of-care variation for our services compared to other specialties.”

Otolaryngologists will, however, be engaging referrals from physicians who make most of their salary in APM contractual arrangements, he noted. “They’ll care a lot about how we manage our FFS patients because that will directly impact the salary of those who refer to us,” said Dr. Harrill, adding that future wrangling about denials and prior authorizations may happen directly with referring physicians if otolaryngologists don’t start paying attention to the necessary infrastructure for cost transparency and begin learning about APMs.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.