In the wake of this year’s landmark health care reform legislation, one of the most hotly debated topics comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in health care spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the upper Midwest and West are colored with a pale yellow hue, which represents areas receiving significantly reduced amounts of Medicare reimbursement. Meanwhile, states such as California, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of brown, which represents the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

The implicit message is that some states, cities and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Rochester, Minn.-based Mayo Clinic, for example, have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone, the result of what they deem inadequate rates that don’t reflect the true cost of care for older patients.

Health Reform Provisions

As part of negotiations leading to the passage of the health care reform package in March, a group of Democratic representatives calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition secured a pledge from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to commission two studies on “unjustified geographic variation in spending and promoting high-value health care” and work toward a more evenly colored landscape (http://house.gov/wu/pdf/3.20.10_Sebelius_Letter_to_Quality_Care_Coalition.pdf).

The more than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, initially pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the House’s health care reform bill late last year. Their provisions weren’t included in the Senate’s health care bill or the reconciliation package, however, necessitating a round of negotiations with HHS to smooth the way for House Democrats to sign on to the final legislation.

One provision directs the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. Guided by those findings, HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius will adjust the rates by Dec. 31, 2012. The second provision calls upon the IOM to conduct a study aimed at changing the Medicare payment system to reward value and quality. An Independent Payment Advisory Board will then use both studies to tweak the Medicare reimbursement rates a second time, by 2014. Secretary Sebelius has also agreed to convene a National Summit on Geographic Variation, Cost, Access and Value in Health Care sometime later this year.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Wash.), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead Congressional negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in health care spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50 percent, depending on the procedure.

“Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar said.

In Washington state, for example, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2007 hovered about $1,600 below the national average, though 12 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less, according to Dartmouth Atlas statistics tabulated from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data.

Despite the specter of a skirmish among urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2007, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received nearly $17,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received less than $10,400 and Atlanta less than $7,700. By comparison, New York netted $12,700, Seattle received $7,300, Rochester, Minn., received $7,200 and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,900.

—Dylan Roby, PhD

Specific Procedures

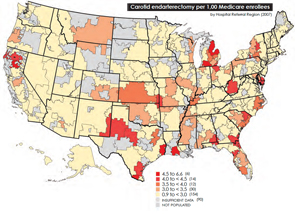

Specific procedures reveal some significant health care trends within individual states. Carotid endarterectomy surgery to prevent stroke, for example, is gradually being replaced by more minimally invasive carotid artery stents. But in Arkansas, carotid endarterectomy procedures defied the national trend, actually rising in prevalence from 1996 to 2005, from 3.6 to 3.8 procedures per 1,000 people. (See map above.) A large part of this trend was due to an increase among women. In Georgia, conversely, rates of carotid endarterectomy, which had been among the nation’s highest, dropped below the national average.

A big question, of course, is whether these trends are necessarily good or bad. An accompanying study by the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice suggests that a decade of data reveals “no general medical consensus regarding the best course of action.” Meanwhile, regional application of the alternative method, carotid stenting, varied by a factor of 30 in 2007. It is this lack of consensus, Dartmouth’s researchers argue, that can drive spending disparities among regions and even among neighboring hospitals. The implication is that much of this variation might be attributable to unnecessary endarterectomy or stenting procedures.

An Unclear Picture

Representatives of higher-spending areas, however, have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care and the infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. After The New York Times printed a story in June that was sharply critical about what was and wasn’t included in the atlas’s calculations and conclusions, the Dartmouth researchers hit back with a testy rebuttal, spurring a terse back-and-forth that seemed to invite bloggers and commentators of all stripes to take sides.

Many experts agree, though, that to get at the underlying cause of disparities, modeling studies like those to be conducted by the IOM will need to consider factors such as a local population’s cost of living, relative health and socioeconomic status.

Dylan Roby, PhD, a research scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Health Policy Research and assistant professor of health services at the UCLA School of Public Health, said the general expectation among health care analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques.

“The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” Dr. Roby said.

But what about outcomes? A study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results for patients (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(5):1278-1285). The study found that more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival. Whether or not this is true of other procedures has been a huge bone of contention between critics and backers of the atlas.

Dr. Roby said the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he pointed out.

The bottom line is that no one yet fully understands all of the factors that account for regional variations in Medicare costs. But the general theme of troubling cost disparities in the U.S. has been bolstered on an international level with the recent release of the Commonwealth Fund’s 2010 ranking of health care in seven developed nations. For the fourth time in a row, the U.S. ranks last in overall performance, including a ranking of sixth in quality and seventh in efficiency, while spending more than twice as much per person than any other country in the survey.

Note: A version of this article originally ran in The Hospitalist, a newsmagazine published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Leave a Reply