While writing my October 2021 article, “Surgeries for Surgeons,” I had no idea my frozen shoulder had a risk factor for developing adhesive capsulitis after decompression shoulder surgery. It’s been several months since my surgery, and I still don’t have full range of motion. I managed to work as if I were the same, but months of compensatory neck and shoulder muscle strain, internalizing stress into my neck and shoulder on a daily basis, apparently led to cervical radiculopathy from a chronic degenerative discs problem unknown to me until a recent MRI. Like all surgeons, I’ve mastered the art of pushing through the daily grind of cases and clinics, as long as I can breathe and move.

That’s why I wanted to share my experience, and the lessons I’ve learned through the process. I hope that other surgeons will learn from it and improve their relationships with their patients, their families, and themselves.

My Injury

In early October, I was looking at my right thumb one day, trying to find the cut that was causing sharp pain, but I was confused when I couldn’t see anything. A few hours later (and every waking moment since), my right thumb and thenar prominence were numb and tingling, sometimes extending to my wrist. Over the next few weeks, my neck became stiffer, and any extension or Valsalva maneuver caused lightening-like paresthesia down my right arm. I wasn’t sure what it was and ignored it as much as I could.

The week all this happened, I had just requested five weeks of short-term disability for the month of December. Stiffness and pain in the right shoulder had progressed with constant cases and typing (I had no scribe). Frankly, I, like many others, had also reached a high level of physical and mental exhaustion, anger, and impatience, and sleep wasn’t restorative due to severe discomfort. In hindsight, the once-a-week physical therapy since my shoulder surgery was a drop in the bucket. Each OR day in a frigid arctic temperature, my neck and shoulder hurt so badly that I had the OR nurse wrap chemical heat packs around my shoulder with Coban dressing under the scrub. (I looked ridiculous.)

Before you judge me, though, I know you would have done the same. You, too, have operated while having an IV in place; you, too, have avoided canceling cases and clinics by pushing your body when you felt horrible. You may have also lived the hypocrisy of saying to others, “We’re human, and we must care for ourselves first,” while our inner voices made it clear that patients always came first. Putting ourselves first was never true during residency, fellowship, or any part of our lives as surgeons.

I learned that I was not alone. Surgeons struggle privately in silence, likely trying to avoid stigma and not wanting to create concerns in patients and colleagues. —Julie L. Wei, MD

Many nights I awoke in the dark, consumed by the paresthesia, without the distraction of busy clinics and cases. It took a few weeks to fit MRIs into my already packed schedule. Finally, they were done on a Monday night at 7 p.m. after a busy clinic day. I was busy in the clinic when I received the MRI report by email. I was overwhelmed with disbelief, fear, and distress after reading it:

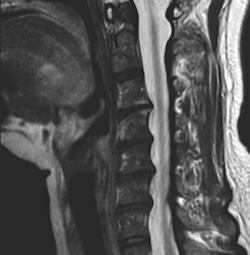

“Multilevel degenerative disc osteophytes indent the ventral CSF space C3-C4 through C6-C7 without significant spinal stenosis. Uncinate spurring with severe right/mild left C5-6 neural foraminal narrowing—correlate with radiculitis”

The shoulder MRI showed adhesive capsulitis and explained why I still can’t zip up my own dress from the back. Neurotology colleagues facilitated an appointment with a neurosurgeon the next week, and I had a follow-up with my orthopedic surgeon. The neurosurgeon spoke to me ahead of the appointment as a professional courtesy and got me scheduled for a cervical epidural.

During the neurosurgery appointment, the physician assistant saw me and did a full exam, and then finally the neurosurgeon came in. (My issues seemed miniscule when I learned he had been with a patient and their entire family to discuss a newly diagnosed massive brain tumor.)

The great news was, I hadn’t lost my motor function (yet). I was informed that over 90% of adults over age 50 have degenerative disc disease, but most may be asymptomatic. I had two choices: 1) live with it, but the longer I have paresthesia the more likely it’s permanent; or 2) have surgery. He showed me a cervical spine model, and a piece of hardware. “I’ll put a titanium plate with three spacers here to increase space between the discs at C6 and other levels.” When I asked if surgery would make the paresthesia go away, he shared that it could, but many wake up from surgery with persistent paresthesia—it’s unpredictable.

“What’s the worst thing that can happen to me during surgery?” I asked.

“I die,” the neurosurgeon said with a smile. “The worst thing that can happen to any patient during surgery is that the surgeon dies during the case,” he joked. I didn’t laugh.

“What are the periop and postop risks?” I asked.

“Death, stroke, paralysis, but all are extremely rare. Also there’s a 1% to 2% chance you’ll have permanent hoarseness if the recurrent laryngeal nerve is impacted, but I think ENTs can do something about that. You’ll have severe throat pain like a tonsillectomy for up to two weeks, sometimes longer. After maybe four weeks, it should get better. You may have the sensation that something is stuck in the throat, called globus, for a while, but it goes away.”

“What about range of motion?” I persisted.

“Oh, yes; you’ll lose about 15 degrees, so you won’t be able to touch your chin to your shoulder on either side.”

“I’m not sure I want to take these risks now, not yet,” I said softly. “

You’re okay. You can live with this. Let’s try one more cervical epidural injection, and if you get worse, call me and we can set up surgery.”

The next day, my orthopedic surgeon was quite concerned. “I looked at your MRI myself, and it’s pretty bad,” he said. “Here’s where it’s severely stenotic and why you developed radiculopathy.”

I shared the recommendation from the neurosurgeon, and the orthopedic surgeon said quickly, “Oh, don’t have that surgery. My father did, and he couldn’t swallow for six months; he aspirated everything and needed a feeding tube. It was awful. They ended up taking the plate out, and he was able to swallow again.”

He injected my shoulder with Kenalog and Marcaine again to try and improve the adhesive capsulitis and range of motion. Leaving his busy office, with countless people in his waiting room, I held back the tears. If I had started, I might not have been able to stop.

Going on Leave

The six weeks leading up to my leave were a blur. I had tried to make up my scheduled calls to minimize the impact to my partners, despite their willingness to do more. My entire team and clinical staff were beyond supportive while I agonized over the guilt, shame, and uncertainty for my life and surgical career, and wondered if I could avoid surgery. Once on leave, I had two episodes of neurogenic vasoconstriction, with my right hand turning blue and ashen gray (like a corpse) for five to 10 minutes, on and off. All I could do was breathe and stay calm until it went away.

I’ve heard that surgeons are at risk for cervical spine issues, but had never known any otolaryngology colleague who had experienced them. As I read online all about the symptoms and treatment options for cervical radiculopathy, I found several studies that had been published in the past two years on the topic of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD) and ergonomics in various surgical subspecialties— especially vascular surgery, robotics, neurosurgery, and laparoscopic or endoscopic surgeries.

On a recent trip to Houston, I shared with a small group of colleagues what I was going through. One showed me his scar from an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion 10 years ago; another shared that he had experienced radiculopathy four years ago. A third colleague said that her spouse, a vacular surgeon, had had to give up his surgical career 8 years ago due to radiculopathy.

I learned that I was not alone. Surgeons struggle privately in silence, likely trying to avoid stigma and not wanting to create concerns in patients and colleagues. The literature bears this out:

-

-

- A survey study of 685 orthopedic surgeons from 27 states found that 59.3% reported neck pain and 22.8% reported cervical radiculopathy. Adjusting for age and sex, surgeons who performed arthroscopy had an odds ratio of 3.3 for neck pain. Older age and higher stress levels were associated factors. Only five surgeons with neck pain and one with cervical radiculopathy ever had an ergonomic evaluation (J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:730-736).

- A literature review on the topic of ergonomics in surgery found WMSDs reported at 66% to 95% for open surgery, 73% to 100% for conventional laparoscopy, 54% to 87% for vaginal surgery, and 23% to 80% for robotic-assisted surgery. Risk factors for injury in open surgery include loupes, headlamps, and microscopes. Unique risks in laparoscopic surgery included table and monitor position, long-shafted instruments, and poor instrument handle design. Robotic surgery was associated with trunk, wrist, and finger strain. Surgeon WMSDs often resulted in disability but were under-reported to institutions (Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:1-12).

- A survey study from the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery on musculoskeletal (MSK) pain and burnout in 569 surgeons reported pain levels of 3 or higher (on a scale of one to 10) in the prior week in 62% of endoscopists, as well as in 71% of open surgeries, 72% of laparoscopic surgeries, 48% of robot-assisted cases, and 52% of endoscopies. Only 120 of 569 surgeons ever sought medical help for pain or discomfort, 38% were currently in pain, 16% had considered leaving surgery, 26% had been on short-term disability during their career, and 4% were on long-term disability. Surgeons who felt physical discomfort that influenced their ability to perform procedures reported lower satisfaction from work, higher burnout, and higher callousness toward people than those not fearing the loss of their career longevity (Surg Endosc. 2019;33:933-940).

- An intraoperative observation and survey study was done using the Rapid Entire Body Assessment score system. Researchers evaluated the presence of postural-related strain and musculoskeletal discomfort, along with the level of ergonomic training and the availability of ergonomic equipment amongst otolaryngology surgeons. Of 70 surgeons, 72% reported some level of back pain, with cervical spine pain being the most common; 43.8% of surgeons reported the highest level of pain when standing, 12.5% experienced pain when sitting, 10% stated that pain impacted their work, and only 24% reported any prior ergonomic training. Residents were equally affected when compared to senior surgeons in observational risk analysis and subjective survey reports (Laryngoscope. 2019;129:370-376).

- Most otolaryngologists experience occupational physical discomfort— rhinologists in particular. Only one study utilized surface electromyography to document physical findings directly associated with endoscopic sinus surgery. Surgeon fatigue and bodily injury were surprisingly frequent in occurrence and were more likely to occur during procedures that are mentally challenging, prolonged, and that require surgeons to operate in fixed position (Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;27:25-28).

- For all otologists and neurotologists, Dr. Lustig and co-authors extrapolated from other surgical professions that cervical and lumbar pain related to prolonged static sitting and neck flexion when working with a microscope are occupational hazards for MSK disorders. Recommendations to incorporate healthy ergonomics into surgical training, as well as adopting correct posture and use of ergonomically designed equipment, may mitigate long-term risks (Otol Neurotol. 2020;4:1182-1189).

-

Lessons Learned

While on medical leave, I’ve been able to replace 10 to 11 hours of caring for others with three hours of daily physical therapy for my neck and shoulder, chiropractor adjustments,decompression machines for my cervical spine, and twice weekly massage therapy to work on the muscular rigidity of my neck and shoulder. In addition, I’ve had weekly counseling to process all my emotions as I face uncertainty while acknowledging years of “self-abandonment.”

Some reflections I’ve had:

- We don’t care for ourselves. As my therapist states, “The thermostat was broken a long time ago.” Our threshold as surgeons is not normal, not healthy, and we aren’t good models despite believing we’re taking care of ourselves. For me, this means I’m no longer cold all the time from years of not eating and being dehydrated. No more middle of the night calf cramps and screaming in pain, no intense headaches, and most of all, my neck actually moves again—I can now change lanes without fear and pain.

- The mind and body have memory. Even when I’m not working, I still think and behave like a surgeon. For example, Tuesday mornings I usually leave the house at 6:30 a.m. to drive 1 hour to the satellite clinic. My first Tuesday on leave, I looked up to see it was 6:24 a.m., and my heart started racing. I also scheduled my PT, chiropractor, and massage appointments back to back, as if I were still in clinic.

- Don’t overdo the cure. I went to the gym daily the first week to walk on the treadmill (on incline) and pushed until my heart rate reached 170. I hadn’t worked out for about two years, so I felt I mustn’t waste time. I lost 3 pounds in five days and felt great about myself. By day six, though, after using the elliptical, I felt sick and then my right hand turned blue again.

- Stay off of work email (mostly). I made a big promise to myself not to log in and check work emails—a promise that lasted only one week. (Although it was kind of a good thing I did check my work emails; I would have missed completing forms necessary to qualify for my bonus.)

- Listen to your body. Over the past two years, my body decided that talking to me was useless; now it screams at me, and I’m still a horrible listener. In 2019, I had two weeks of unexplained hives, intense pruritis, and facial/ lip angioedema. All the bloodletting from lab work was normal; my allergist concluded that stress was the cause. I developed a hypertensive crisis during the pandemic, always with severe headaches. And how quickly I forgot my increased frequency of emergency visits for chest pain.

- Taking time off is vital. Time off has allowed my body and mind to slow down, and I can observe my sensations, anxiety, and restlessness. I do feel shame and guilt as though I’ve “abandoned” everyone: patients, colleagues, and med students. But what’s really sad is realizing that rushing around for 19 years, speaking on burnout and well-being, hadn’t made me protect myself better.

- We can’t do everything. I’ve squeezed all my responsibilities as a mother, wife, friend, mentor, and division chief into every second, including nights and weekends, when I’m not in my 10 to 11 hours of daily clinical work. So have you. It comes at a physical, emotional, and mental cost, though. I’ve mastered squeezing life into my career by doing everything possible to prove I’m worthy of being loved, and no less competent than my male colleagues. The system push for ever-increasing productivity made it worse.

- Less stress = greater connections. During the weeks away from work, my husband and I have developed a far deeper connection than we have ever had in our 18 years of marriage. He sees my vulnerability and has reassured me. He sees me smile, and I notice we are laughing again—often. We have more authentic conversations. I now have a sense of hope and empowerment, and I truly believe that whatever happens, we’re committed to my health above all else.

I didn’t write this article to be a victim or martyr. Those who know me can say I did too much and could have avoided this. I couldn’t.

But I’m not alone. As I face my future, I plan to choose myself, my marriage, my health, and my life first. I’m so grateful that, at age 51, I still may have much life left to live, regardless of whether or not I’m a surgeon.

Dr. Wei is chair of otolaryngology education for the University of Central Florida College of Medicine. She is also an associate editor on the ENTtoday editorial advisory board.