Big changes are coming to the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), the exam that brings a great deal of stress to potential pre-med students and probably exerts as much influence as any other factor on where those students end up attending medical school.

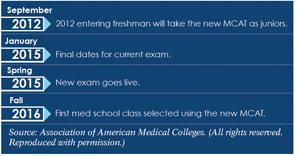

The changes, which are set to begin with the 2015 test, will put new emphasis on appreciation for and knowledge of social and behavioral sciences to encourage future physicians to pursue more education in these areas and bring a more diverse pool of applicants to med schools—one that is perhaps not quite so dominated by biology and chemistry majors. The new test, part of a group of changes initiated by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), could eventually make for more well-rounded doctors throughout medicine. The AAMC is also working on changes to applications and suggested interviewing techniques.

The announcement has prompted some otolaryngologists to consider which physician traits could be improved upon in their subspecialty and to think about how far-reaching the changes to the MCAT will really be in terms of the doctors who treat patients.

Understanding People

Darrell Kirch, MD, president and CEO of the AAMC, said the motivation for the changes is the acknowledgement that good patient care involves more than diagnosing, prescribing and operating. It’s about how doctors talk to patients. It’s understanding them and their personal situations and cultural backgrounds, and it’s understanding how social and behavioral factors affect individual health.

Understanding social barriers and helping patients overcome them might mean avoiding a hospital readmission, he said. “We have finally realized there are some very powerful determinants of health that have been underemphasized in the test historically,” Dr. Kirch said. “We’ve known for a long time that social and behavioral factors can be every bit as influential in determining a person’s health as their genetic makeup. The new test attempts to include social and behavioral sciences in the same way that we’ve included natural and physical sciences historically…. We’ve realized the breadth of knowledge that’s required to be a capable physician.”

In a letter to pre-med students in which he talked about the MCAT changes, Dr. Kirch wrote, “It is about understanding people—how they think, interact, and make decisions…. After nearly 60 years, I still remember my pediatrician, Dr. Bramley—not for his class rank or MCAT exam score, but for his kindness, compassion, and how much he truly cared.”

The new test will reflect updates in knowledge of the natural and physical sciences, and it will include two new sections: “Psychological, Social and Biological Foundations of Behavior” and “Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills.” The first will test students’ understanding of behavior, perception, culture, poverty and other concepts from psychology, sociology and biology, as well as knowledge of basic research methods, scientific reasoning and statistics skills. The second will test analysis and reasoning skills by asking test takers to critically analyze information in reading passages. It will include ethics, philosophy and cross-cultural studies content.

The new test will take a little more than six hours, a significant increase from the four and a half hours the test currently takes. Medical schools will remain free to determine how to weigh the performance on each section in their admissions decisions.

“Somebody could be a social scientist, somebody could be a humanist—in terms of their college preparation—and still become a fine otolaryngologist. Medicine is a broad field with many entry points.”

“Somebody could be a social scientist, somebody could be a humanist—in terms of their college preparation—and still become a fine otolaryngologist. Medicine is a broad field with many entry points.”—Darrell Kirch, MD, AAMC President and CEO

A Multidimensional Approach

The changes to the application and the suggested changes to the interviewing process will put more emphasis on how students respond to certain situations, such as ethical dilemmas. The idea is that responses will give reliable reflections of a student’s character and ability to handle complex interpersonal scenarios. “It’s a multidimensional approach to better assess applicants,” Dr. Kirch said.

Another purpose for the changes is to open the door to different kinds of undergraduates, he said. While pre-med students must have certain core competencies, there are many ways to cultivate them. Dr. Kirch, for example, was a philosophy major as an undergraduate. “Somebody could be a social scientist, somebody could be a humanist—in terms of their college preparation—and still become a fine otolaryngologist,” he said. “Medicine is a broad field with many entry points.”

Otolaryngologists might be technically inclined, Dr. Kirch said, but “they’re the first to say that they didn’t enter medicine to simply become a technician. They entered medicine to meet the needs of the patients.”

G. Richard Holt, MD, MSE, MPH, MABE, professor emeritus in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio and an adjunct faculty member with the Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics there, said the majority of physicians are already ethical and humanistic. But he feels the changes to the test are worthwhile. “My notion is probably that about a quarter of physicians have some issues with their bedside manner, their ability to relate to patients, communication skills, perhaps even their professionalism,” he said. “I think that’s the group of people we really need to target.”

The skills needed to relate to patients in a way that will help their medical care are not easy to hone, he added. “I tell the students and residents that it is relatively easy to treat disease,” he said. “It’s much harder to treat the person. And by that I mean all aspects of the human being.” With medical schools teaching more humanities, bioethics and professionalism, the MCAT changes are a logical addition to the learning continuum, he said.

Many pre-med students already take undergrad courses in humanities, philosophy and ethics, he said, but those tend to be the students who are already “tuned in” to the importance of those areas. “If the medical schools would inform pre-medical advisors and pre-med students of just why these courses are important to physicians, rather than a strict requirement, then that would hopefully also broaden the awareness of the breadth and depth of the life of a physician and minimize the tendency toward a too-focused curriculum in college,” he said.

A Step in the Right Direction

Robert Miller, MD, executive director of the American Board of Otolaryngology and physician editor of ENT Today, said he is “skeptical” that the new test features would have much of an effect. “If you’re going to try and teach communication and cultural sensitivities and things like that, doing it in college probably is not going to be nearly as effective as doing it in medical school,” he said.

But he said the possibility that the changes might attract a wider array of applicants is appealing. “Frankly, I think sometimes there’s too much emphasis on science in college education,” he said. “I think, personally, I would rather see somebody come in, not with a science degree but with a degree in other areas. That might indicate a more balanced person and somebody who’s not just focused on the science. So that would be consistent with what they’re trying to do.”

He added, “I’m not saying this isn’t a step in the right direction, but it’s more of a baby step.”

Fred Telischi, MD, chairman of the department of otolaryngology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, said that while most otolaryngologists have a sufficient human touch, today’s environment has led to a decline in face time. “There’s more tendency to use technology to make a diagnosis rather than perhaps spending a little bit more time with patients,” he said. “And as reimbursement has gone down and managed care has become more prevalent … people probably feel more pressure to see patients faster so they can get more volume into the day.”

He added that making changes to the MCAT—and exposing more undergraduates to topics beyond the hard sciences—might not make a difference to a lot of people, but it’s bound to help in some cases. “They may have an ‘aha’ moment in one of those classes that stays with them the rest of their career,” he said. “It may make incremental improvements in some, it may make a big improvement in a few individuals, and that could be a good thing for medicine in general.”

Dr. Miller said that time—in this case, a decade or more—will tell. “It’s an interesting proposition they’ve put together, but, like any experiment, you need to see how it works out,” he said. “And we won’t know that for another 10 or 15 years, until the doctors who are accepted through this mechanism are out into practice. “The results of this proposal need to be carefully monitored to see if it makes any difference or not,” he said.

Leave a Reply