Traditionally, nights in sleep centers are abuzz with activity. However, some of these nights are becoming quieter as sleep centers find it harder and harder to stay open in the wake of the twin storms of decreased reimbursement and increased regulation.

It will likely take a well-thought out, creative action plan that takes into account new third-party payer and regulatory climates to help sleep centers surive and—ultimately—thrive.

Where Did the Reimbursement Go?

Several factors affect reimbursement for sleep studies, the largest contributor to a sleep center’s revenue. The most significant change is the advent of the home sleep test (HST), which is replacing about 30 percent of in-lab polysomnography (PSG). Starting March 13, 2008, CMS published a National Coverage Determination to allow HST to diagnose sleep apnea and, as of Jan. 1, 2013, private insurers have followed that lead. The use of HSTs has grown dramatically, not surprising when HSTs are reimbursed at approximately 30 percent of in-lab studies. In fact, while CMS reimburses for both HST and PSG, many private insurers now require that sleep studies be done at home, except in cases with confounding comorbidities such as diabetes, congestive heart failure or hypertension. This change in reimbursement has caused a dramatic and sudden shift in the services performed by sleep centers.

James O’Brien, MD, a sleep medicine physician in private practice in Boston, projects that by year’s end, the number of full PSGs will be down by 50 percent, while the volume of HST will rise by 75 percent. This increase will be a function of the cost-effectiveness of HST, and also of its convenience. For patients, performing a test in the comfort of their own homes rather than in unfamiliar labs can make the testing more attractive, with a great deal less anxiety involved.

Many sleep centers, small and large, have already become casualties of this new marketplace. The precipitous drop in reimbursement has left them struggling to pay their staff, along with rents or mortgages. Additionally, the rise in HST has necessitated a shift in staffing. Centers that once staffed nocturnally for PSG now need a smaller night shift and must add a daytime shift to provide HST equipment and train patients in its use.

Primary Care Physicians

As the pool of reimbursement dollars shrinks, competition for a share is mounting. Insurers are beginning to contract with larger preferred service providers, leaving smaller operations out of the picture. Also, some diagnostic companies are working with primary care physicians (PCPs) to offer sleep studies through their offices. The physician prescribes an HST for a patient he or she believes suffers from sleep apnea, and the company arranges for the test and provides a sleep physician to interpret it. Reimbursement is then shared between the PCP and the diagnostic company.

This model of sleep testing raises many questions about the efficacy of the treatment offered through a PCP office. Who prescribes the CPAP machine for patients diagnosed with sleep apnea—the PCP or the interpreting physician? Who in the office has the necessary knowledge, experience and time to train patients diagnosed with sleep apnea on CPAP machines? Who troubleshoots for patients having equipment problems? What is the impact on compliance, already low for CPAP use, in cases where patients do not have access to a qualified sleep professional? Ultimately, the question is whether or not a PCP can treat sleep apnea effectively.

An Australian study published in March of this year compared PCP management of sleep apnea to that of sleep centers (JAMA. 2013;309:997-1004). Re-

searchers concluded that patients treated by a PCP experienced outcomes relatively equivalent to those seen in sleep center patients. However, a closer look at the participating PCP offices revealed that their nurse practitioners had received intensive training in testing for and treating sleep disorders. In fact, one nurse had 20 years of experience in sleep medicine. Would typical PCP offices that do not employ staff with this level of expertise still be able to deliver results that approach those achieved in a sleep center?

—Kathryn Hansen

The Burden of Increased Regulation

Another blow, new regulations, comes with a cost for compliance. There are three types of regulations affecting centers’ bottom lines:

- Accreditation. Previously, sleep centers did not have to be accredited, but most states now require accreditation from either The Joint Commission or the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Accreditation will most likely be mandatory in all states within the year.

- Credentialed staff. Professionals employed in sleep centers are now required to demonstrate competencies in diagnostics and treatments through exams, CE credits and peer review.

- Proof of effectiveness. Centers must demonstrate that they are effective through patient compliance and improvement data.

Kathryn Hansen, executive director of the Kentucky Sleep Society and a sleep center management consultant, says that these changes should come as no surprise. The use of sleep testing has become almost epidemic as more and more physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants recognize the effects of sleep disorders on overall health. “While the increased recognition of sleep dysfunction is good,” she said, “we cannot continue to incur more costs and increase availability of our services without more regulation as we have seen in other specialties, including cardiology, pulmonology and home health care.”

How to Take Charge of the Future of Sleep Centers

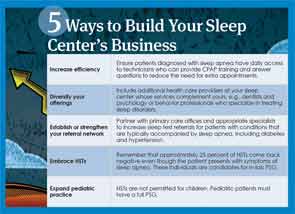

Navigating this new environment requires a dramatic overhaul of the way a sleep center operates. “Centers need to look at their practices and figure out how to be as efficient as they can as they adapt to the new environment of changing reimbursement and patient needs,” said Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, assistant professor of surgery in the division of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Kentucky, medical director of the St. Joseph’s Sleep Wellness Center in Lexington and ENTtoday editorial board member. One key way to do this is to facilitate patient access and turnaround time. Have a CPAP technician available every day to see patients who come in for the results of their sleep study and train them on the use of their new equipment. This saves the time and money involved in scheduling an additional appointment to pick up the machine and learn how to operate it.

While streamlining operations, centers should also diversify their services and expand the diagnostic tests and clinical services available at the facility. Hansen suggests that practices incorporate dentists who specialize in treating sleep problems and psychology professionals who offer neurodiagnostic testing and behavioral treatment to attract more referrals and new patients.

Sleep medicine is an integral part of the overall management of many conditions, and this ubiquity provides numerous opportunities for referrals. But, in this new world, centers can no longer wait passively for new patients to materialize. They must take an active role in locating people who need their help.

Partnering with PCP offices is an excellent strategy to broaden a center’s patient base. PCPs can prescribe sleep studies for patients with conditions often accompanied by sleep apnea, including diabetes, arterial fibrillation and snoring. They can refer those at higher risk for sleep apnea, such as individuals who are overweight or who have large necks. Reaching out to PCP offices and reminding them of the value of a sleep study can improve the overall health of these patients, while establishing or increasing a physician’s referral network.

Electronic health records may become an important instrument for increasing PCP referrals. For centers attached to a network that includes a PCP office, EHRs make it easier to screen for patients with health histories that make them candidates for sleep studies and enable easy communication among all the professionals involved in the patients’ care. The depth of information they contain can reduce redundancies in diagnostic testing, providing significant cost savings. They can benefit centers not attached to a network by facilitating smooth and fast information transmission to home care or medical equipment companies. When EHRs are attached to a cloud network, their data can be collected to prove the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of treatment.

HSTs can also be a source of referrals for PSG. Twenty-five percent of HSTs will yield negative results even though the patients are displaying symptoms of sleep apnea. This could be happening for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the patients only have apnea when sleeping on their backs, and during the test they slept on their sides. Perhaps undergoing the test made them so nervous they did not really sleep that night. These patients with “suspicious negatives” should undergo a full, in-lab PSG to find the source of their symptoms.

Dr. O’Brien recommends that centers also expand their pediatric studies, given the fact that HST is not permitted for children. Pre-operative sleep apnea testing can be done on pediatric tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy candidates and repeated post-operatively to confirm the surgery’s success.

The transformation of the sleep medicine marketplace, while drastic, is not the first sea change the health care industry has experienced. The advent of Medicare is a prime example of a revolutionary shift in the way medical professionals did business. Now, as then, those who survive are those who can adapt. “Don’t be a passenger on the bus,” said Dr. O’Brien. “Changes in sleep medicine are happening so fast, you have to change direction quickly to keep up, so drive your bus.”

Leave a Reply