Once the province of neurosurgeons, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak repair is now handled mostly by otolaryngologists. This change has occurred over the past couple of decades, during which time the evolution of endoscopic tools and techniques has made possible extracranial rather than intracranial repair. The success rate for repairing these leaks from below has reached about 90 percent, particularly for small leaks (Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1119-1125).

But despite the high success rate for the repair of leaks from small skull base defects, several challenges remain, otolaryngologists say. Among these are leaks that result from larger defects caused by endoscopic intracranial work.

Laryngoscope. 2004;114:255-265. Copyright 2004 the American Laryngological. Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc.

“Otolaryngologists must understand the difference between routine cerebrospinal fluid leak repairs of small defects such as those seen after trauma, as opposed to large defects seen with endoscopic skull base resections that require extended, multi-layer reconstruction,” said Rodney J. Schlosser, MD, professor and director of rhinology and sinus surgery at the Nose and Sinus Center, Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Vascularized Flaps

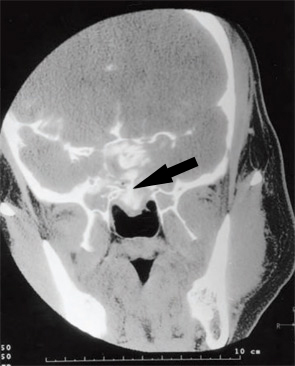

One advance from the past five years that helps to meet the challenge of repairing CSF leaks from large skull base defects is the use of vascularized flaps, or arterially based flaps, to close the leak, according to Bradley Marple, MD, professor of otolaryngology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Although the practice is not new, he said, the use of the flaps to reconstruct the skull base is.

“Typically, for large CSF leaks, a lumbar drain is placed so that it can decrease the CSF pressure, which in turn decreases the stress placed on the repair site,” said Mas Takashima, MD, director of the Baylor Sinus and Allergy Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “For extremely large defects encompassing most of the skull base, a nasoseptal flap pedicled off of the sphenopalatine artery can be used to cover the defect and provide a resilient, vascularized flap to repair the hole.”

According to David W. Kennedy, MD, professor of otorhinolaryngology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, the practice is still evolving, but most centers now use these flaps when the defect is major and is at a site where flap closure is possible. “The evidence suggests that for large defects there is an advantage to using arterially based flaps,” he said.

Spontaneous Defects

Clinical Endocrinoogy. 2000;52L43-49. Copyright 2000

Blackwell Science Ltd.

Spontaneous defects, another type of difficult leak otolaryngologists must distinguish from routine CSF leaks, are often associated with elevated intracranial pressures, according to Dr. Schlosser. These types of leaks, he said, require adjuvant medical therapy to avoid long-term failure.

Kevin C. Welch, MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill., also emphasized the importance of adequately treating these types of leaks.

“One of the overarching concepts in the management of CSF leaks, primarily spontaneous CSF leaks, is that the surgery fixes only the active leak,” he said. “Medication may be necessary to manage elevated intracranial pressure. In some cases the placement of a shunt is required.” Without these additional treatments, he said, there is a theoretical risk that the underlying condition may cause recurrence or a leak in a new location.

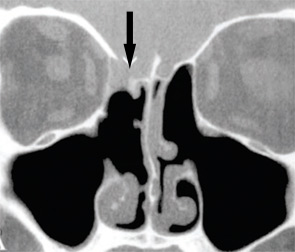

The Frontal Sinus

According to Dr. Welch, CSF leaks that involve the frontal sinus are the most challenging for otolaryngologists to repair, both because of the surgical skill required and due to the inability of current instrumentation to effectively navigate the necessary anatomical regions.

“Reaching frontal sinus CSF leaks can tax the capability of the surgeon as well as the limitations of the current instrumentation,” he said. “However, many frontal sinus CSF leaks can be closed endoscopically or with the assistance of a small frontal sinus trephination.”

“The evidence suggests that for large defects there is an advantage to using arterially based flaps.”

“The evidence suggests that for large defects there is an advantage to using arterially based flaps.”—David W. Kennedy, MD

Antibiotics

The subject of whether or not to use antibiotics in patients with CSF leaks remains controversial because evidence of its benefit in this setting is lacking. According to Dr. Welch, evidence from a number of large studies indicates some benefit in using antibiotics in the setting of traumatic leaks; smaller studies show an incidence of meningitis in up to 29 percent of unrepaired cases of CSF leaks (Rhinology. 2005;43:277-281; Am J Rhinol. 2000;14:257-259).

Despite the inconclusive evidence regarding the necessity of antibiotics, Dr. Welch uses third-generation cephalosporin when repairing CSF leaks because of concerns about meningitis.

The possibility of meningitis in patients with CSF leaks is one reason physicians still prescribe antibiotics, said Dr. Takashima, adding that he and his colleagues typically use a first-generation cephalosporin as a preoperative antibiotic, rather than a broad-based antibiotic. To date, they have not had any patients with infectious complications, Dr. Takashima said.

While acknowledging that some patients with CSF leaks appear to have fewer problems with recurrent meningitis when given a prolonged course of oral antibiotics, Dr. Kennedy does not typically treat his patients with an oral antibiotic. Occasionally, he will use an antibiotic in patients with a history of multiple episodes of meningitis. He emphasized that antibiotics are always used at the time of leak closure.

“Medication may be necessary to manage elevated intracranial pressure.”

“Medication may be necessary to manage elevated intracranial pressure.”—Kevin C. Welch, MD

Intrathecal Fluorescein

Currently, the most sensitive test used to detect a CSF leak is intrathecal fluorescein. According to Dr. Welch, the use of this test is indicated when the site of the leak is unknown or to confirm a leak in an area in which one is suspected. It may also be used to ensure that a leak stops during surgery.

The test, however, is not typically used, he said, “if the surgeon is going to remove a tumor and the removal of that tumor results in a CSF leak or if the surgeon is performing a routine endoscopic sinus surgery and inadvertently causes a CSF leak.”

The test, which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication, must be used correctly to avoid complications. According to Dr. Kennedy, seizures have been reported with doses as low as 0.2 cc of 10 percent fluorescein. Because of this potential complication, he emphasized the need for otolaryngologists to inform their patients that this test is not FDA approved for intrathecal use.

When used appropriately, however, the test carries little risk of complications. Both Drs. Welch and Kennedy use the test at its suggested dose of 0.1 cc of 10 percent fluorescein mixed with 10 cc of the patient’s CSF or preservative-free saline and slowly injected over five minutes.

For Dr. Kennedy, this test is superior to the radioactive intrathecal tracer test. “Those tests have a significant false positive rate,” he said, “and that is something which probably many otolaryngologists are not aware of.”

Although intrathecal fluorescein is currently the most sensitive test used to identify CSF leaks, Dr. Kennedy said that a colleague of his, Erica Thaler, MD, has demonstrated efficacy with an electronic nose to detect these leaks (Laryngoscope. 2002;112(9):1533-1542); the same technology, he said, is used currently in agriculture and bioterrorism.

“Otolaryngologists must understand the difference between routine cerebrospinal fluid leak repairs of small defects…as opposed to large defects seen with endoscopic skull base resections that require extended, multi-layer reconstruction.”

“Otolaryngologists must understand the difference between routine cerebrospinal fluid leak repairs of small defects…as opposed to large defects seen with endoscopic skull base resections that require extended, multi-layer reconstruction.”—Rodney J. Schlosser, MD

Closing from Above

Although otolaryngologists are now able to close most CSF leaks endoscopically, they may still have to team up with a neurosurgeon or hand a case off to a neurosurgeon in some cases.

“There are some situations in which the intracranial approach is necessary,” said Dr. Marple, noting that some of these situations are dictated not by the defect in the skull base but by what is associated with that defect. “For example,” he said, “if there was a large encephalocele associated with an important structure, that may be addressed from above, not because of the defect, but because of the encephalocele.”

Dr. Welch emphasized that even patients with very large defects with meningoencephaloceles may be candidates for endoscopic CSF repair, however.

A Successful Closure

To successfully repair even the most routine CSF leak, otolaryngologists need to keep in mind several basic tenets of repair. For Dr. Kennedy, the issues that get otolaryngologists into trouble most often are knowing when to close a leak created during an endoscopic procedure and the importance of preparing the surface on which to lay a graft.

“It is really important for otolaryngologists to know that if an otolaryngologist inadvertently creates a CSF leak during sinus surgery, that leak should be closed as early as possible unless there is any suspicion of intracranial bleeding,” he said.

Another key to achieving a successful closure, he said, is to prepare the surface so that the graft or flap can be placed on a nice flat surface right on the skull base.

For Dr. Takashima, the first step is to find the origin of the leak. “Don’t expect to just lay tissue over a large portion of the skull base in hopes of sealing the leak. Usually this results in failure,” he said.

Dr. Takashima also emphasized that sometimes the dura over a small CSF leak has to be opened up more to perform a good “bath plug” surgical repair.

“Although this sounds counterintuitive when repairing a leak,” he said, “the fat needs to be initially placed inside the cranium prior to pulling it back out to seal the leak. If the dura is not adequately opened enough to do this, a failure is more likely to occur.”

Leave a Reply