November is a special time of year for the country. Much of the talk around the country centers around the mid-term elections and in our cover story this month, we dig into what issues influence the votes of physicians and otolaryngologists; truly interesting stuff and great topic for conversation at the dinner table. But for the sake of this public forum, I won’t talk any more politics. A 2017 survey by the American Psychological Association found that 26% of workers felt political debates at work left them feeling tense or stressed and 40 % found that the divisive, distracting environment caused a negative outcome as evidenced by reduced productivity or poorer work quality (Published May 2017).

November is a special time of year for the country. Much of the talk around the country centers around the mid-term elections and in our cover story this month, we dig into what issues influence the votes of physicians and otolaryngologists; truly interesting stuff and great topic for conversation at the dinner table. But for the sake of this public forum, I won’t talk any more politics. A 2017 survey by the American Psychological Association found that 26% of workers felt political debates at work left them feeling tense or stressed and 40 % found that the divisive, distracting environment caused a negative outcome as evidenced by reduced productivity or poorer work quality (Published May 2017).

What I would rather talk about is a subject that is nuanced in a way that is poorly understood by most but has a large

impact on the work satisfaction of many. How do people climb the ladder of society leadership? And even though this month’s story is slanted toward academic societies, the lessons we learn can be applied to all facets of our work and even private life. How can I fast-track to partnership? Who decides whether or not I get on the school board? I want to be involved with hospital leadership but don’t know where to start. How do I become the next president of the Triological Society?

These are all great comments and questions I hear routinely in my everyday life. As a chair of an academic department, one of my official responsibilities is to support my faculty, fellows, residents, staff, and medical students. Many take this to mean mentoring: giving advice, using my experience to offer support and guidance, and providing feedback to help my mentee’s personal and professional development.

But, if you ask my faculty and trainees what my role should be, mentoring is only a portion of what they expect me to do. Most, if not all, want to progress to some type of leadership role. Or, maybe they want the top fellowship in the country or to interview at the best residency program in an area where their family is from. Regardless of the exact situation, they are looking for me to be a sponsor. A mentor gives advice but sponsors promote their proteges directly, using their personal networks to place them in leadership positions or committees. While a mentor gives suggestions on how a mentee can expand his or her network, a sponsor gives proteges their network connections and helps make new connections for them.

And, in my opinion, being a mentor is fun and one of the most rewarding aspects of a leadership position. Being a sponsor is much harder—and often uncomfortable—but is one of the most influential things I can do to help those looking for my assistance. Data shows that women and underrepresented minorities have more mentors but are promoted at a far lower rate than white men. According to the Center for Talent Innovation, the vast majority of women and multicultural professionals need support to advance their careers but receive it less often than white males (Published October 9, 2018).

Everyone who knows me knows I love to golf. It is too easy for me to only sponsor those who also golf or share my interests. For those of us fortunate enough to be in a position to be a sponsor, we need to make a conscious effort to put aside our personal biases to also sponsor those who don’t look or act like us, but are worthy of promotion and advancement. Being a mentor is a blast. Being a sponsor is not always fun, but its effects can be profound.

Thanks for reading and I look forward to talking next month.

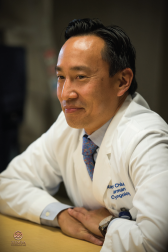

—Alex