TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.com.

TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.com.

Explore This Issue

January 2017Background

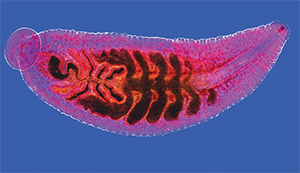

Underside of leech.

© M. I. Walker/ Science Source

Leeches have been used clinically to help salvage venous-congested skin flaps since 1960. Numerous articles have described their success in benefitting the survival of local, regional, and free flaps. However, the clinical application remains imprecise.

The theory behind leech therapy is that leech bites decrease venous congestion in compromised skin flaps. Venous congestion is detrimental to skin flap survival, because it leads to microcirculatory thrombosis and blood stasis. The active enzyme in leech saliva, hirudin, is a powerful anticoagulant. This allows blood to flow more freely at the bite site. The objective of leech therapy is to establish temporary venous outflow until further neovascularization has taken place. Typically, leeches are applied to the compromised area of the flap every several hours and are removed once they are no longer biting the tissue. Patients must have antibiotic coverage (such as fluoroquinolones, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, or a second- or third-generation cephalosporin) during leech therapy to reduce the risk of infection (commonly caused by Aeromonas hydrophilia). Hemoglobin should be monitored daily, because treatment can lead to sudden anemia requiring blood transfusions. This article reviews the evidence surrounding the use of leeches to salvage failing local and regional skin flaps to the head and neck area.

Best Practice

Leech therapy is a temporary modality to decrease skin flap venous congestion until further revascularization occurs for venous outflow. Leech therapy is not effective in the setting of arterial flow compromise. Future studies with local and regional flaps are needed to fully understand when is the critical time to initiate leech therapy and to determine its optimal duration of treatment (Laryngoscope. 2016;126:1271–1272).