Case Scenario

You are the mission director for a short-term medical mission to a less developed country with a need for otolaryngology. The country, which is poor, has few physicians, with otolaryngologists located only in the larger cities. After locating the sleeping quarters and stowing the team’s equipment, you and your team are given a tour of the clinic and regional hospital and find them to be quite basic—that is, the resources provided to care for patients are minimal. You see that the diagnostic equipment, operating room, and recovery room facilities are far less adequate than you had been led to believe. It becomes apparent that the scope of the surgical procedures you and your team came prepared to perform may need to be reconsidered.

Svetlana Lukienko/shutterstock.com

Your otolaryngologist host has mobilized a number of nurses and translators to assist the team in obtaining histories and performing physicals on the patients, many of whom have walked for several days to be seen. The translators seem to have a serious lack of medical knowledge, however, and it is difficult to determine just how well your questions and comments are being translated to the patients.

In spite of the agreement with your hosts that you and your team would only be addressing otolaryngologic clinical issues, quite a few of the patients are requesting care for medical issues outside of the scope of otolaryngology—such as diabetes, skin sores, burns on the extremities, hernias, and deformities of the fingers and toes. One family has carried in a grandmother in a makeshift gurney to see your team, when in fact she has suffered a severe stroke from hypertension.

There are, however, plenty of patients with otolaryngologic disorders. The team diagnoses facial paralyses, facial skin cancers, head and neck tumors, cleft lips and palates, severe nasal deformities, malunions of mandibular fractures and mandibular tumors, vocal fold paralyses, chronic ear disease, and chronic sinus disease. You also are asked to see a number of prospective patients the host otolaryngologist introduces to you and the team as “requiring” facial plastic surgery procedures. These individuals are dressed much more affluently than the rest of the patients and are waiting in a side room where tea and sweet biscuits are being served.

You and your team are given a tour of the clinic and regional hospital and find them to be quite basic. You see that the diagnostic equipment, operating room, and recovery room facilities are far less adequate than you had been led to believe. It becomes apparent that the scope of the surgical procedures you and your team came prepared to perform may need to be reconsidered.

The remainder of the patients, who seem genuinely in need of medical and surgical care, are dressed in clean but poor clothing and, in some cases, beg you for help. Many others seem quite shy, perhaps because they have never seen or been around Americans before.

It appears that patient records are handwritten and rarely stored for safe-keeping. Informed consent in this region of the country amounts to the verbal approval of the senior male in the family, not necessarily that of the patient.

The resident physicians in the team are focusing their attention on the more challenging head and neck and otologic disorders and are eager to operate on these patients. They are pressing for an extensive surgical experience that will result in many patient photographs to share with others back in the States.

As you and your team meet to discuss potential surgical candidates, a number of important diagnostic and patient care inadequacies become obvious. There is a CT scanner in the hospital, but it comes with an acknowledged history of poor maintenance and frequent breakdowns—although currently it appears to be working. There are no trained audiologists at the clinic, but a Bekesy audiometer was found in a storage closet. On the positive side, the anesthesia machines are functioning properly, and there is an instrument sterilizer with intact seals.

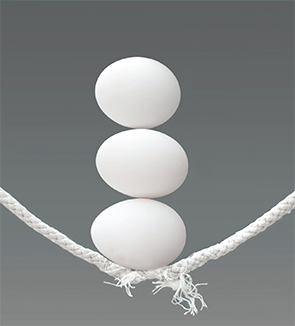

As you lead the patient care team in an in-depth discussion of patient selection for surgical procedures, you realize that the decisions made by the team could have far-reaching social/cultural implications, as well as a tremendous impact on the safety and outcomes of each individual patient selected.

How should you proceed?

Discussion

Short-term medical missions outside the United States can be professionally and personally rewarding—and usually are. Many altruistic healthcare providers spend precious free time planning and participating in medical missions, giving needed medical and surgical care to thousands of disadvantaged persons around the globe. The secondary missions of teaching and supporting the country’s local physicians and otolaryngologists are nearly as important as direct patient care. Additionally, the good relations that are developed by caring, compassionate American physicians and nurses with individuals of other cultures represent our commitment to helping others. All in all, medical missions can be positive and altruistic when conducted appropriately. A number of major points can be emphasized in the planning and conduct of medical missions.

Mission Planning

Much of the success of a medical mission lies in proper planning.

Pixelbliss/shutterstock.com

Much of the success of a medical mission lies in proper mission planning, as well as proper conduct of the mission according to the plans. The most important initial steps are to identify the country in need of assistance and to select the best local physicians to host the team and the mission. It may be difficult to ensure that the host physicians have the proper credentials, capabilities, integrity, altruism, and organizational skills to manage the on-site conduct of the mission, so references must be checked. The mission plan should include the following concerns and requirements: types of surgical cases to be performed, standards of care for the patients, limitations of care and selection of patients, cultural considerations, socio-political-economic issues in the host country that could affect the mission, and, of course, ethical considerations.

It is important to know the precise capabilities and available equipment and facilities at the host site. Many surgical procedures require a specific preoperative diagnostic evaluation to determine the suitability of a surgical procedure for any given patient. You might anticipate requiring precise audiometric evaluations for otologic procedures, imaging for head and neck and sinus procedures, and basic laboratory and electrocardiographic tests for surgical clearance. Failure to confirm the proper infrastructure at the host facility can result in overestimation of the types of surgical procedures that can be performed.

Mission planning should also include an emphasis on patient safety, quality care (even considering the infrastructure limitations), quality improvement over mission iterations, impact assessment of the mission on the host community, teaching opportunities of host physicians, and the importance of maintaining positive international relations. No longer can medical missions be conducted with minimal planning and maximum optimism—reality must prevail.

Scope of Practice

Medical missions to developing countries should not be undertaken just as an opportunity for training residents or medical students in surgical procedures. In fact, it may well be that the most experienced otolaryngologists should be performing the difficult portions of the surgeries to achieve the best chance for a successful outcome. After all, the American otolaryngologists will be leaving these patients after just a few weeks of postoperative care, so while teaching others is indeed a secondary mission, the primary mission is to provide the most expert care for the patients. In this scenario, the resident physicians on the mission trip were excited about getting to perform difficult cases on patients whom they would only know for a short time and in the context of quite diverse cultural differences. Of course, the residents should participate, but the senior otolaryngologists should decide just what part of the appropriately selected procedures would be amenable to resident performance.

The procedures otolaryngologists perform on a medical mission should be similar to those they routinely perform in their own practice. It is not a time to perform surgical procedures the otolaryngologist has not performed since residency. The team composition should appropriately be organized to include the range of generalists and specialists that reflects the types of procedures included in the scope of the mission planning. This same concern would apply to other specialties, as well. Patient safety and positive patient outcomes are best served by practicing well within the scope of the individual physician’s experience and expertise.

Patient Selection

Proper selection of patients rests with the integrity, ethics, and expertise of the mission leadership. Along with scope of practice, the other important parameters for proper patient selection and patient safety include the capabilities of the surgical team, the infrastructure of the facilities, proper working condition of the equipment, a history based on adequate translation, a pertinent physical examination, an informed consent that at least includes the assent of the patient, proper diagnosis of the disorder, perioperative care that includes blood banking and nursing care as needed, and the provision of physician follow-up care. Too many blank spots in the assessment and selection of the appropriate procedure for a given patient can lead to a disaster that may not be recoverable. The availability of a crash cart for cardiac arrests must be confirmed during mission planning, as these events can occur even in the best of circumstances. Requesting photographic evidence of the equipment and facilities before embarking on the mission can greatly aid in planning. Do not be caught unaware of the limitations of the host site or facilities.

It is appropriate to select patients who have the most urgent need for surgical therapy and whose surgery is supported adequately by the facilities and equipment on site. In this scenario, the host otolaryngologist appears to be prioritizing individuals whose disorders are lower in severity and who may be friends of the otolaryngologist. This is not coherent with the ethical principle of “social justice,” where equality and severity of need are emphasized. The mission leader should discuss this impropriety with the host physician in a very tactful manner, indicating that their mission goals require the team to prioritize patient surgery by need only. Mission leaders will have to use professional communication skills to help the host otolaryngologist understand the situation without compromising the relationship.

Ethical Treatment of Patients

It is very important for participants in medical missions to prepare themselves by studying the culture of the host country, paying special attention to customs, social norms, folkways, and interpersonal etiquette. The mission team has to remember that they are guests in the host country, and although they will strive to contribute to the improved health of the host community, their proper interaction with the patients and their families will be remembered far longer than the surgical procedures. Condescension toward staff or others at the host site is clearly inappropriate. Loud and obnoxious behavior must be avoided. Acts such as shaking hands with single women, touching patients, and asking direct questions may be out of bounds, depending on the culture.

The hallmarks of a culturally successful medical mission include treating the patients as you would in the U.S., showing compassion and understanding, paying attention to the patient by listening well, advising the patient and family of surgical options (including no surgery) and risks, and acting in all matters with integrity. Ethics and professionalism know no geographic boundaries. Additionally, all efforts must be made to obtain an informed consent, while understanding that language and translation barriers might diminish the information exchange. It is generally held that consent to treat is implied if the individual presents to the triage area for care; however, implied consent is more appropriate with medical therapy, while informed consent is typically used for more extensive care, such as surgery, where the risks are greater.

Records, whether written or digital, should be kept secure in the U.S., with copies held by the local otolaryngologist for follow-up care. If the mission team returns to the same location over time, which is recommended, then the medical records will be necessary for professional follow-up and outcomes evaluations. Patients should be required to give their verbal, head-nod, or written consent to being photographed, and they should be informed that the photographs will only be used for documenting their postoperative course, to encourage other health providers to volunteer for medical missions, or for teaching medical professionals. Most importantly, the photographs should not be placed on social media sites or otherwise used inappropriately—after all, photographs of patients, no matter what the setting, represent private health information.

The patient-physician relationship is based on trust, which can be difficult to achieve in a foreign country in a short encounter; however, it is the responsibility of the otolaryngologist to develop the best possible relationship with the patient, who is entrusting her/his health to someone from another country. Confidentiality of patients’ personal health information can still be important to them, even in rural regions of developing countries. Surgical care should be provided to an individual regardless of gender, religion, race/ethnicity, social status, or personal situation.

In the United States, four ethical principles are integral to patient care—autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and social justice. We tend to hold autonomy in the highest regard, perhaps reflecting the fact that our country was founded on a belief in personal free will. This is often not the cardinal ethical principle in other countries, where decisions may be made by other family members. While we strive for beneficence in caring for our patients, medical missions require at least an equal emphasis on nonmaleficence—“first, do no harm.” You cannot have a bad outcome on an inappropriately selected surgical patient and then leave the patient to be cared for by others in the host country. Therefore, a good case exists for making nonmaleficence and social justice the primary ethical principles that guide us in our conduct of medical missions. That is not to say we should minimize our efforts to help patients and allow them to make their own health decisions—rather, it is this author’s opinion that we should not leave a person’s health worse than when we arrived to “help.”

Conclusion

Short-term medical missions can be altruistic and contribute to the improvement of health in both treated individuals and a local community. Proper mission planning prior to travel can generate goals and guidelines that will usually lead to a successful mission. Identifying the appropriate host otolaryngologist,

understanding the status of the host facilities and equipment, and learning the capabilities of the facility staff are all very important. The country’s culture and folkways must be studied so that the team will understand the proper manner of interaction with patients, families, and staff. Appropriate patient selection is critical and must be coherent with the expertise of the surgical team and the capabilities of the host facility. At all times, compassion, honesty, integrity, trustworthiness, and professionalism must be foundational to the care of patients. Ethical principles must be adhered to, and the dyad of beneficence and nonmaleficence must be balanced or favored to “do no harm.” Medical missions can be personally and professionally rewarding, potentially changing the lives of individuals who might not otherwise have that opportunity.

Dr. Holt is professor emeritus in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.