Even though the evidence is now clear that cochlear implants (CIs) work, many patients who would benefit from them still do not have them, and challenges and questions remain about when to offer the devices and how to ensure patients are reimbursed for them. A panel of experts gathered at the Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting discussed available options for patients with unilateral and bilateral hearing loss.

Craig Buchman, MD, Lindburg Professor and chair of the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said that approximately 40 million people in the U.S., and 350 million around the world, suffer from hearing loss. While 1.4 million people are CI candidates, he added, “We’re only looking at 100,000 cochlear implant recipients in the U.S. Less than 10% of people who are CI candidates are actually getting these devices. That’s sort of a sad story.”

He said the field is past the point of having to prove the merit of these devices. “We’re no longer in the business of proving that the cochlear implant works—our biggest chore going forward is learning how to deliver this to the people who need it.”

Panelists delved into some of the issues surrounding CIs as they discussed patient cases.

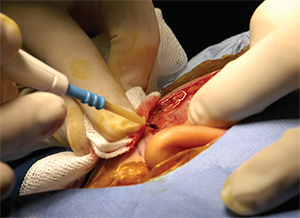

Cochlear implant surgery.

© AJPhoto / Science Source

Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss

The first case involved a 52-year-old man with sudden sensorineural hearing loss in his left ear that had begun 17 months before. He’d had difficulty hearing people in front of him when they were more than three or four feet away and had stopped going to restaurants because of trouble hearing in noisy settings. He’d had no history of noise exposure and his imaging was normal. He tried a contralateral routing of signal (CROS) hearing aid, but said it actually made hearing worse in noisy situations.

Brian McKinnon, MD, MBA, MPH, vice chair of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Drexel University in Philadelphia, said he would consider evaluating this patient for a central processing problem, given the severity of his hearing loss at a relatively young age. “He seems remarkably debilitated,” he said.

Other panelists said they would move straight to pursuing a CI, but said getting reimbursed is a huge challenge for single-sided hearing loss. “When we first embarked on this about 15 years ago, it went really well. Nobody asked any questions,” said J. Thomas Roland, MD, chair of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at New York University Langone Medical Center. “But now it’s getting more difficult.” He said he usually has four or five patients at various levels of appeal, and one patient who is an attorney has sued his insurer over CI coverage.

Alan Micco, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Northwestern University in Chicago, said he agreed, but said,

“It’s a mixed bag; the ones with tinnitus seem to love it, but a lot of them don’t like the sound quality particularly when the hearing is very normal in the opposite ear.”

Dr. Buchman said the patient ended up getting a CI as part of a study that has funding for single-sided hearing loss, and has done well. “I think, overall, patients are doing a lot better” with CIs, he said. “I’m hopeful that the kind of information that’s starting to come out of some of these studies will start to change the carriers’ minds.”

Bilateral Hearing Loss

In another case, a 66-year-old patient had experienced bilateral hearing loss for 20 years and was frustrated with his difficulties both in quiet settings and with background noise. The softest sounds he could hear were in the 95- to 100-decibel range at high frequencies and in the 60- to 70-decibel range at low frequencies, with word recognition scores (WRS) of 60% for the right ear and 68% for the left. He’d been wearing hearing aids for 10 years.

Dr. Micco said he would be sure to check on the age and quality of the hearing aid being used to be sure it’s a good fit, and might consider an implantable hearing aid as an intermediate step.

Dr. McKinnon said a patient’s performance with hearing aids is an important factor when considering an implantable aid. “The problem is that if they’re not happy with their hearing aids, there’s a significant likelihood they’re not going to like their middle ear implant,” he said. “I’d be fairly hesitant because he’s not happy with his hearing aids.”

Panelists generally agreed that they’d use a long electrode in this patient, although Dr. McKinnon acknowledged literature showing good results for short ones. He’d approach this as a hearing preservation case, which is how he tends to approach most of these types of cases.

Panelists added that, anecdotally, they’ve had good success with a hearing aid in one ear and a tethered CI in the other. When it comes to bilateral cochlear implants, Dr. Roland said, patients need to be informed that they could lose some of the “finer qualities” and nuances of sound. “I encourage them to wait and take some time and check back with me in another six months to a year,” he said.

Dr. Buchman said these kinds of cases are difficult. “These patients that have significant low-frequency loss but potentially enough hearing to preserve—it’s hard to know what electrode to pull; it’s hard to know what kind of surgery to do; it’s hard to know whether it should be on the lateral wall or modiolar,” he said. “When patients have lots of low-frequency hearing, I don’t think it’s that difficult a decision. But this particular spot, I think, is the cutting edge of trying to understand how we should act.”

The patient received a CI as part of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services expanded criteria study, and has seen “nice gains” in his hearing. Dr. Buchman added, “I think the story is that the Medicare criteria are just still way too stringent.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Take-Home Points

- Fewer than 10% of people who are candidates for cochlear implants have received the devices.

- Insurance coverage for cochlear implants continues to be a struggle for single-sided hearing loss.

- When considering bilateral cochlear implants, it is best to counsel patients that they are likely to lose some of the finer qualities of sound.