© Mark_Kostich / shutterstock.com

HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancers respond better to radiotherapy than other treatments. However, despite this and other benefits, radiation therapy has a host of drawbacks, including long-term side effects and even treatment-related morbidity in some cases. Given these disadvantages, debates continue regarding whether or not radiotherapy is the right way to treat these patients.

Explore This Issue

November 2019On the positive side, radiation combined with chemotherapy results in high cure rates: 85% of patients with locally advanced disease live five years or longer (Lancet. 2019;393:40–50). For lower stages of HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer, the survival rate is even higher, and only radiation (no chemotherapy) is required. Radiotherapy is also non-invasive and doesn’t require anesthesia. “Because of these benefits, radiation can be given to the vast majority of patients, even those with other significant medical problems,” said Stephen Ramey, MD, assistant professor of radiation oncology at Augusta University in Georgia.

David Clump, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the department of radiation oncology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, said that HPV+ small volume oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas have a failure rate of less than 10% when treated with radiation therapy delivered over six weeks (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1333–1338). For patients with more advanced disease, cytotoxic chemotherapy is combined with radiation to improve cure rates.

Although early T-stage oropharyngeal cancers can also be treated surgically, these procedures may be followed by adjuvant radiation, with or without chemotherapy, depending on pathologic features, said Ken Byrd, MD, associate professor of head and neck surgery at Augusta University.

Disadvantages of Radiotherapy

On the negative side, patients who undergo radiation treatment must often endure fatigue, skin erythema and breakdown, dysphagia due to inflammation of tissues, mucositis, pain, loss of taste, lymphedema, and a higher risk of depression. In the long term, these patients have risks of fibrosis and decreased range of motion of the neck, along with xerostomia and dental caries. “Fibrosis of pharyngeal and cricopharyngeal musculature can lead to longer term swallowing difficulties and risk of aspiration pneumonia,” said Brandi R. Page, MD, assistant professor of radiation oncology and molecular sciences, and assistant professor of otolaryngology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. “Severe toxicities such as osteoradionecrosis or fistula are possible.”

When patients receive both chemotherapy and radiation treatment, mucositis is a common acute toxicity. Mucositis persists and results in pain, dysphagia, and weight loss. It requires the use of gastrostomy tubes and narcotics to combat the pain. Patients also suffer from sequelae such as fatigue, nausea, emesis, nephrotoxicity, and ototoxicity. “Such acute toxicities can require breaks in treatment, which can lead to suboptimal treatment efficacy,” said Cherie-Ann O. Nathan, MD, professor and chair of the department of otolaryngology/head and neck surgery at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center and director of head and neck surgical oncology at Feist-Weiller Cancer Center, both in Shreveport, La.

Patients with HPV+ oropharynx cancers are often in their 40s and 50s, so long-term toxicities can impact them for decades. Furthermore, the percentage of patients living after treatment is increasing because these patients are often younger and healthier than previous patient cohorts.

The combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy is being actively tested in clinical trials, and is likely to eventually enter the standard-of-care in one form or another. —Andrew Sikora, MD, PhD

Given the downsides, Dr. Clump said it’s important to address side effects with patients. He encourages them to visit survivorship clinics, where preventive techniques are deployed or side effects are identified early on.

Why Radiotherapy Can Be Harmful

In the longest of long-term survivors, Dr. Page has seen localized effects of radiotherapy corresponding to how much radiation a patient receives. “This is most often related to fibrosis and stenosis of the microvasculature and atherosclerosis of microscopic arteries leading to decreased blood flow, and therefore scarring and hardening of musculature and soft tissues,” she said.

Due to microscopic vasculature hardening, as well as organ damage, organs that may have had exposure, such as the thyroid gland, submandibular glands, and parotid glands, may experience hypofunction. “Patients who experience symptomatic hypothyroidism due to radiotherapy exposure have a higher mortality rate if they aren’t placed on a regular monitoring schedule,” Dr. Page said.

Longer term scar tissue can cause increased risk of stroke due to carotid arterial stenosis. Fibrosis and fistulae can cause chronic infections and pain with life-threatening consequences. Osteoradionecrosis, which can cause chronic pain, infections, and decreased ability to chew and eat, is treated with surgery, antibiotics, and controversial and costly treatments, including hyperbaric oxygen or pentoxifylline, Dr. Page said. Before speech and swallowing exercises were introduced during radiotherapy, patients would become dependent on feeding tubes and later experience atrophy of pharyngeal musculature, leading to increased risk of deadly aspiration pneumonia.

Proper and careful implementation of patient education, nursing care, frequent access to physician expertise, and empowerment during radiotherapy are important factors in the management of expected acute term side effects. “In the survivorship phase, patients can work together with their medical team to maximize quality of life,” Dr. Page added.

Should Treatment Protocols Change?

The younger patient population and favorable prognosis associated with HPV+ oropharynx cancers carry with them a need to decrease treatment toxicity, without compromising oncologic outcomes, Dr. Nathan said.

Dr. Ramey agreed, adding that clinicians need to be cautious before moving away from established curative techniques. According to American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines, treatment de-intensification for HPV+ tumors shouldn’t be done outside of a clinical study (J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1578–1589).

A variety of early-stage clinical studies have shown that decreased radiation doses to the lymph node regions in the neck greatly reduced the amount of radiation needed after surgery and lowered the overall dose of radiation and/or chemotherapy (J Clin Oncol. 2019 Published online Aug. 14, 2019. doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01007; J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1909–1918). “These studies have promising results with excellent cure rates and decreased side effects,” Dr. Ramey said. “However, they still require testing in larger clinical trials comparing these decreased intensity treatments to the current standard of care.”

Along these lines, Dr. Nathan said that multiple large retrospective database studies and prospective studies have already demonstrated evidence in favor of de-escalation (Laryngoscope. 2012;122 Suppl 2:S13–S33; Oral Oncol. 2018;79:64–70). “Studies have shown that when some clinicians didn’t prescribe radiotherapy for patients with low-risk disease after surgery, that many patients showed improved functional outcomes,” she said. Cramer’s National Cancer Database retrospective study determined that patients had similar outcomes when radiotherapy or chemotherapy with radiotherapy were omitted in low-risk patients (Head Neck. 2018;40:457–466).

Proceed with Caution

As exciting as the concept of de-escalating treatment for patients with HPV+ oropharynx cancers might be, Andrew Sikora, MD, PhD, associate professor and vice chair for research in the department of otolaryngology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said that it’s important to make sure that the desire to improve patients’ quality of life doesn’t lead to worsening excellent survival outcomes. “Any de-escalation strategy needs to be based on a foundation of solid clinical trials evidence,” he added.

Another important point is that a significant number of patients with HPV+ oropharynx cancer have extensive smoking histories. “We don’t know as much about this population as we should,” Dr. Sikora said. “We know that they have worse outcomes than HPV+ oropharynx cancer patients without a history of tobacco use, but this is not reflected in our current staging system, which automatically downstages patients with a HPV+ tumor. Therefore, these patients are at serious risk for undertreatment.”

Overall, rather than focusing single-mindedly on de-escalation of HPV-associated oropharynx cancer, Dr. Sikora believes tools need to be developed that will allow clinicians to risk assess individual patients and deliver the treatment they need. “In many cases, this will involve de-escalating treatment relative to what has been the standard, but for others we will need to intensify treatment,” he said. “We need to invest in the necessary research to develop the algorithms and predictive markers that will allow us to evaluate a patient’s tumor, and determine with confidence the treatment with the greatest chance of cure and lowest risk of long-term toxicity.”

Dr. Ramey added that radiotherapy is an excellent treatment option for many patients and that patients should have the chance to discuss this highly successful treatment option with a radiation oncologist. “However, there is no one right way to treat every patient with oropharyngeal cancer, since treating physicians need to take into account a patient’s preferences, the specifics of each patient’s cancer, and a patient’s other medical co-morbidities,” he said. “Therefore, clinicians must be a part of a team helping patients make an informed decision.”

Outlook

Radiotherapy is going to be part of the treatment strategy for patients with HPV+ oropharynx cancer for a long time, Dr. Sikora said. “Right now, standard chemo-radiotherapy regimens are very effective, but also very difficult for patients,” he said. “The combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy is being actively tested in clinical trials, and is likely to eventually enter the standard-of-care in one form or another. Even patients treated with surgery often require adjuvant radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy to maximize their chance of a long-term cure. So radiotherapy is not going anywhere anytime soon.”

Nevertheless, the way radiation is delivered has evolved, and will continue to do so. “The development of intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), which focuses radiation on the tumor and decreases the dose received by normal tissues, was an important step toward decreasing toxicity,” Dr. Sikora said. “We are now actively discussing the de-escalation of radiation for patients with HPV+ oropharynx cancer with favorable characteristics. There is also the future possibility, if supported by clinical trials, of reducing or replacing chemotherapy with immunotherapy for some patients, since overall it has a less punishing toxicity profile.”

Dr. Page also believes that radiotherapy will remain in use for the foreseeable future, despite its drawbacks. “It’s still the main curative therapy, particularly for patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas,” she said. “While current clinical trial efforts include examining de-escalation therapy to try to reduce either chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both, more work needs to be done to further elucidate the extent of therapy needed to adequately treat this disease.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

How Radiotherapy Works

Radiotherapy works by damaging the DNA in cells. It can potentially kill all cells, but there is increased killing in malignant cells due to the fact that their DNA repair mechanisms often don’t function normally. When cancer cells with a significant DNA injury start to divide, they fall apart and die. “Because cancer cells divide more rapidly than normal cells and aren’t able to repair DNA damage as well, they are more likely to die than normal cells close to the cancer,” said Dr. Ramey.

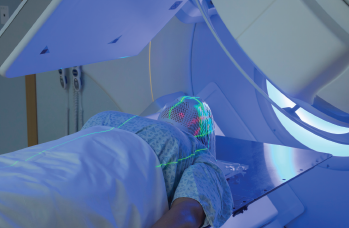

For head and neck cancers, photons are generated within a machine called a linear accelerator and modulated as they leave the machine with a technique called intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). “As the photon interacts with the patient, its DNA damage is either ignited directly by interacting with the dividing cells or via indirect actions with water within the body,” said David Clump, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the department of radiation oncology, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, Pittsburgh, Pa. “As the photon interacts with water within the body, the water molecule is split to create a free radical that subsequently damages the DNA of dividing cells.”

The process is optimized by using technology to deliver a quality-assured, reproducible dosing of radiation that aims to minimize toxicity to normal tissues while targeting a tumor and its expected drainage pattern. “Treatments are then delivered over a series of weeks using a specific dose of radiation per treatment as well as a specific number of treatments called fractions,” Dr. Clump said.

Radiotherapy works best on cells in the active replication phase, outside of the G0 (resting) stage of the cell cycle. “As a result, actively replicating cancer cells are the best targets of radiotherapy and tend to respond more quickly,” said Dr. Page. “Normal tissue will exhibit some signs of radiotherapy response sooner or later in a course of therapy, depending on its radiation sensitivity.”

In addition to damaging dividing cells, radiotherapy also works by stimulating an immune response against the tumor. “The interaction of radiation with the immune system is complicated, and radiation can both suppress and enhance anti-tumor immunity depending on how it is delivered and what other treatments the patient receives,” said Dr. Sikora—KA