Image Credit: iqconcept/shutterstock.com

A recent recommendation from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to keep Medicare graduate medical education (GME) funding at the same level for the next 10 years could make it difficult to train the next generation of physicians, academic physicians say.

In 2012, an IOM committee co-chaired by Gail Wilensky, PhD, and Don Berwick, MD, MPP, both former directors of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), was tasked with reviewing the way the current GME system is governed and funded and determining whether it’s producing a physician workforce that is meeting the needs of the U.S. population. In July 2014, the committee released a report, “Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education,” recommending that Medicare maintain its current GME funding levels, adjusted for inflation, while gradually moving to a performance-based system. The committee determined that a phased approach over a 10-year period would minimize disruption for institutions accustomed to receiving Medicare GME funding in roughly the same way for decades.

The demand for GME is greater than what is currently being funded. To maintain the current level of funding is to fall behind; you’re not keeping up with the cost of training the residents at the status quo level.

The demand for GME is greater than what is currently being funded. To maintain the current level of funding is to fall behind; you’re not keeping up with the cost of training the residents at the status quo level.—Terry Tsue, MD

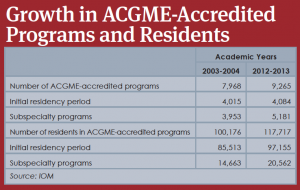

In a New England Journal of Medicine commentary published shortly after the release of the report, Drs. Wilensky and Berwick explained that “forecasts of future physician shortages are variable and have been historically unreliable,” and “current programs are producing an increasingly specialized workforce that is insufficiently responsive to local and national needs” (New Eng J Med. 2014;371:792-793). In concluding that increasing Medicare funding is not essential to increasing the number of physicians in the U.S., the committee noted that the number of residency slots increased by 17.5% over the last 10 years. This growth occurred in spite of a cap on government funding of GME instituted as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

The report also recommends the following:

- Create a GME policy council within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop and oversee a strategic plan for Medicare financing and create a GME Center within CMS to manage the operational aspects of GME funding.

- Fold the current direct GME expenditures and indirect cost funding streams into one fund with two subsidiary funds: a GME Operation Fund to support existing programs and a GME Transformation Fund to finance new, innovative programs as well as new programs in needed specialties and underserved areas.

- Create a new Medicare payment methodology based on a national per resident amount with a geographic adjustment, and distribute funds directly to GME sponsoring organizations. Implement performance-based payments based on Transformation Fund pilot payments.

- Keep Medicaid GME funding at the state’s discretion, but have Congress mandate the same level of transparency and accountability as promised for Medicare GME funding.

Maintaining the Status Quo

The IOM’s recommendation to freeze GME funding for the next 10 years troubles some academic physicians, who say medical education programs need more, not fewer, federal dollars.

You’re going to stop attracting the very brightest people into the field of medicine if you’re having a funding problem.

You’re going to stop attracting the very brightest people into the field of medicine if you’re having a funding problem.—Stacey Gray, MD

“The demand for GME is greater than what is currently being funded,” said Terry Tsue, MD, the Douglas A. Girod, MD, Endowed Professor of head and neck surgical oncology, vice chair and professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, and physician-in-chief of the Cancer Center at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City. Dr. Tsue previously served as associate dean for GME. “To maintain the current level of funding is to fall behind; you’re not keeping up with the cost of training the residents at the status quo level,” he said.

Dr. Tsue said innovations in medical education, such as the use of surgical simulators and information technology, have driven up the costs of residency training exponentially. “It’s a lot different than when we didn’t have technology way back in the dark ages when I trained,” he said. “All that costs more money. To train a resident now is so much more expensive, and every year it gets much worse.”

New Funding Sources?

Dr. Tsue said that since funding hasn’t kept pace with the need for more residency slots, programs have had to be creative in finding alternative sources, including private funding and clinical revenues. But most programs, he said, fund approximately half of their slots using federal dollars, and no other mechanism exists that will fill the gap if federal funding is discontinued.

As the IOM report noted, in 2012 alone, public tax dollars contributed more than $15 billion to support residency training, with more than 90% coming from Medicare and Medicaid.

“The absolute biggest issue is that I don’t know where the funding will come from,” said Stacey Gray, MD, director of the Harvard Medical School Otolaryngology Residency Program in Boston. “Most of the people going into medicine are already fairly in debt when they start their residency training, and they continue to stay in debt during that time because the salary is significantly different than it is for full-time physicians. You’re going to stop attracting the very brightest people into the field of medicine if you’re having a funding problem.”

Dr. Tsue agreed. “There’s really no other mechanism that will be able to fill the gap in terms of training these residents.” Eventually, medical schools will find themselves with fewer students, he said. “The government is pushing for the training of more medical students but not producing more jobs for training them. No one will go to medical school if they can’t get a job afterward,” he said.

Funding Surgical Specialties Versus Primary Care

Otolaryngology may not be affected as strongly as other specialties by a reduction in Medicare GME funding, however. Without federal funding, hospitals that fund GME out of their operating revenues are more likely to continue to do so in the more profitable surgical specialties such as otolaryngology, rather than in primary care, said family medicine physician John Zubialde, MD, associate dean for graduate medical education at the University of Oklahoma School of Medicine in Oklahoma City.

Dr. Zubialde also takes issue with the workforce estimates the IOM used in drafting its report. He pointed out that 2013 data from the Association of American Medical Colleges reported a growing shortage of physicians and a need to increase GME to meet physician demand, especially in primary care (2013 State Physician Workforce Data Book. Available at aamc.org). “We are going to need more doctors, and we want to drive growth in ways that meet the nation’s workforce needs and not just needs of local hospitals,” he said.

Stephanie Mackiewicz is a freelance medical writer based in California.