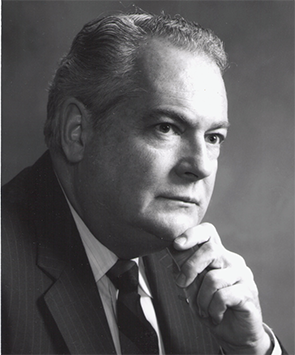

Paul H. Ward MD

UCLA

Paul Ward passed away on April 9 of this year. He was one of the true giants (an overused term, in my opinion, but Paul really was a giant) of our specialty. There have been and will be many more formal obituaries and tributes to Paul and his many professional accomplishments. I’d like to share with the ENTtoday readers a more personal tribute to Paul based on my interactions with him.

Explore This Issue

October 2015I matched in the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) general surgery program in 1973 with the intent of becoming a surgeon in the then-budding field of liver transplantation. I had done research in this area throughout medical school and was even lucky enough to rotate for three months at the University of Colorado, where Tom Starzl, MD, PhD, was doing some of his pioneering work, so I knew where my professional life was heading. I enjoyed my time in general surgery at UCLA, but then, as a PGY-2, I did a rotation on Head and Neck, the title for the UCLA otolaryngology section. Well, I had thought I was happy in general surgery, but after rotating on the head and neck service with Paul, Tom Calcaterra, MD, Nando Canalis, MD, and the other wonderful faculty members of that time, I decided to change my career plans. Paul had been chief of the division for only a few years, but he, along with his great faculty, had already developed a research and educational program second to none. Their enthusiasm and vigor for their young program was palpable and very attractive to me.

Although he loved research and assembled a great team in that realm, my main contact with Paul was in education. Paul was a very tough taskmaster who expected nothing less from the residents than the time and effort he put into his practice, which was a daunting standard. Arriving in his office even before the residents made pre-surgical rounds, he stayed until the last bit of work was completed, which ensured the residents at least attempted to work as hard as he did.

Paul’s Wednesday conferences were some of the most educationally outstanding sessions I’ve encountered. Paul combined tough questioning with great humor in working residents through cases using the Socratic teaching method at its best. Making rounds on patients with Paul was equally enlightening.

Paul was very demanding in the OR. The chief resident had to have personally reviewed all of the imaging studies, histopathology slides, lab work, and any other information prior to entering the OR. Once the specimen was excised, Paul would take the operating resident to pathology to orient the specimen or look over the frozen sections. He was a very fast surgeon and would leave the residents to close the wound. Occasionally, the residents might slow the pace a bit at this point, but every now and then, a familiar voice would come over the OR 6 PA system from the observation area, “Don’t let the euphoria of closure slow you down.” And the pace would move back into “Paul mode.” Paul was famous for his sayings, some of which are in the sidebar.

In addition to focusing on education at UCLA, Paul was very much involved in education at the national level. He was a member of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education Otolaryngology Residency Review Committee and served an eighteen-year term on the American Board of Otolaryngology (ABOto) that included several years as the exam chair. I had the honor of overlapping with Paul for four years on the ABOto Board of Directors.

Many men and women are desirous of leaving a legacy. Paul leaves a legacy that is larger than most and covers so many areas. He will be remembered for his bigger-than-life persona. He was outspoken and did not mince his words. As tough as he could be on the residents, you knew it was tough love. I recall one occasion when a resident wasn’t performing up to his capabilities, and the decision was made at a faculty meeting that Paul needed to counsel the resident. It turns out the resident was having to moonlight a great deal to help pay for a piece of real estate he had purchased. Paul’s solution was to co-sign the resident’s loan so he could focus on his education.

Paul was a very accomplished researcher, and he and his team, led by Vicente Honrubia, MD, added prodigious amounts of knowledge, particularly with regard to the vestibular system. Although Paul’s practice focus was head and neck surgery, he always considered himself to be an otologist at heart.

But, for Paul, the accomplishment he was most proud of is the residents he trained and, in particular, the number of future chairs he produced. I was chair number thirteen of a total that I’m sure is now well into the twenties. He truly looked upon the residents as his children, and we were part of his family. Suzanne and Paul opened their condo to us regularly for dinners and parties. As another example of his “family” concept, Paul was always available after we finished training for consultation and mentoring on many topics. I know he put in a “good word” for us to the right people to aid our career development. He absolutely beamed when one of his residents became a chair.

Another trite, overly used phrase is “They broke the mold.” Well, in my opinion, they really did break the mold after Paul came into this world. We currently have a great cadre of educators and researchers in our specialty. Some even closely approximate Paul in their accomplishments, part of which is a result of Paul’s (and his peers of the time) commitment to the specialty. Still, Paul was one of a kind in so many ways.

Some may find my version of Paul’s obituary to be a bit casual, not extolling his many official, professional accomplishments in a more traditional format. However, having known Paul for so many years, I know he would prefer a more lighthearted and irreverent approach. His patients, the specialty, and his trainees will miss him. He truly made this place a better world. And he had a lot of fun doing it.