Oropharyngeal cancers, including cancers of the tonsils, soft palate, posterior pharynx, and base of the tongue are not diseases that most otolaryngologists-head and neck surgeons come across in their day-to-day practice. In fact, the American Cancer Society estimates that only 8950 new cases of pharyngeal cancer, including cancers of the oropharynx and hypopharynx, are diagnosed each year in the United States, with an estimated mortality of 2,100 annually (CA Cancer J Clin. 2006; 56(2):106-130). Men are three times more likely to be afflicted than women, and onset is usually around 60 years of age.

However, in recent decades, we have seen a rise in oropharyngeal cancer in patients under 45 years of age. These patients don’t fit the risk profile with typical exposures to tobacco or alcohol. – -Erich M. Sturgis, MD, MPH

Younger Patient Population Reveals New Risk Factor

However, in recent decades, we have seen a rise in oropharyngeal cancer in patients under 45 years of age, said Erich M. Sturgis, MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Head and Neck Surgery and Epidemiology at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and an ENToday Editorial Board member. These patients don’t fit the risk profile with typical exposures to tobacco or alcohol, whereas in the past, 85% to 95% of oropharyngeal cancer patients had a history of such exposures.

What we are discovering is that these younger, non-smoking patients are infected with high-risk (oncogenic) types of human papillomavirus [HPV], an extremely common sexually transmitted infection often found in females with high-grade cervical dysplasia or cancer, Dr. Sturgis said. Although the mode of transmission is not fully understood, oral/genital contact is an important possibility.

HPV types 16 and 18 are typically responsible for most high-grade intraepithelial lesions (such as high-grade cervical dysplasia) that may progress to carcinomas. Molecular evidence indicates that the same oncoproteins or growth-promoting proteins (E6 and E7 of HPV high-risk types, such as 16) that inactivate the p53 and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor genes and promote genomic instability in cervical cancer do likewise in head and neck cancers (J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(21):1626-1636; J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(5):736-747).

In 2003, researchers working on the International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Study compared 1670 patients who had oral cancer (both oral cavity and orophayngeal sites) with 1732 healthy volunteers from nine countries (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95(23):1772-1783). HPV-16, the strain most commonly found in cervical cancer, was also detected in most of the oropharyngeal cancers. Participants with cancers containing the HPV-16 strain were three times as likely to report having had oral sex as those with tumors not containing HPV-16. There was no difference between men and women in terms of how likely the virus was to be present in these cancers.

Women with high-grade cervical dysplasia need to be informed that they may transmit HPV to their partners putting them at risk for such infections and potentially HPV-associated malignancies, said Dr. Sturgis.

Small Impact on Detection, Diagnosis so Far

Anyone with a persistent unilateral soar throat or a neck mass, often called ‘swollen glands,’ should be referred to a qualified ENT or head and neck surgeon for further evaluation, said Maura L. Gillison, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Oncology at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Md.

Unfortunately, screening for oropharyngeal HPV infection or premalignant conditions is not very good presently, said Dr. Sturgis. At best, it’s like a ‘pap smear’ of the tonsils whereby we brush off cells that are then sent to the cytologist who does a similar viral oncogenic typing as for cervical pap smears. Such swabs or smears and oral rinses are used to test exfoliated cells in clinical trials, but are not routinely utilized or standardized for the oropharynx. Screening for invasive disease of the oropharynx is by physical examination augmented by CT or MR imaging with invasive biopsy required for a definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, the majority of oropharyngeal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. Molecular and epidemiologic studies by Dr. Gillison and her colleagues strongly suggest that HPV-positive (usually type 16) oropharyngeal cancers comprise a distinct molecular, clinical, and pathologic disease entity that is causally associated with HPV infection and that has a markedly improved prognosis (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000; 92(9):675-677).

Studying the Link

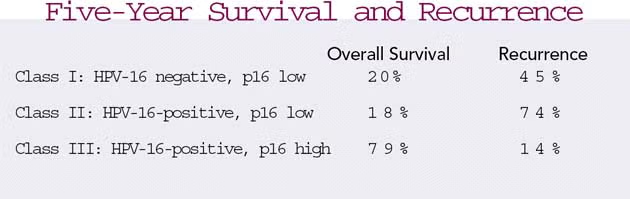

To further explore the role of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer, researchers at Yale University School of Medicine conducted a study among 78 patients to determine whether HPV-16 was present or absent, as well as to gather information about levels of a protein known as p16 (J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(5):736-747). High levels of p16 (overexpressing) have been reported in cancers caused by HPV, whereas tumors with low levels of p16 (nonoverexpressing) that are HPV-16-positive may have been caused by factors other than HPV.

The researchers divided subjects into three groups based on the presence of HPV-16 and p16 in tumor tissue and assessed the five-year rates as shown in the chart above.

The researchers conclude that tumors within Class III have the best prognosis.

Although this is a significant discovery, on a more practical basis p16 is highly unlikely to be useful in oral cancer screening in the immediate future as very little is known about the risk factors and natural history of an oral HPV infection or the predictive value of HPV detection for a diagnosis of or risk for oral cancer, Dr. Gillison told ENToday.

At Johns Hopkins Hospital, Dr. William Westra and I make the diagnosis based upon HPV in situ hybridization and the specific demonstration of HPV to the nucleus of the tumor cell, said Dr. Gillison. In our laboratory, HPV in situ data and p16 are strongly correlated and the p16 data does not add to the HPV data in terms of etiologic classification or prognosis.

The HPV detection was performed by a less specific test-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-thereby necessitating the class I, II and III designation. In our research there are HPV-positive and HPV-negative cases; this is the critical designation, Dr. Gillison said.

Dr. Sturgis noted that significant confounding by stage/treatment specifics, tumor location, and smoking status exists in most studies reporting HPV; this impacts prognosis and makes definitive conclusions regarding prognosis premature. A clinical pathologist does not usually check for HPV status and these tumors are not typically studied unless patients are part of a clinical trial or research study.

However, because many metastatic cancers involving the neck of unknown primary origin likely originate in the oropharynx, this may become another area of clinical utility of HPV testing.

Developing New Treatments

Right now, regardless of whether a person is HPV-positive or -negative, you still treat their oropharyngeal cancer the same way, said Dr. Sturgis.

Current treatments include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, surgery, or combinations of these based upon the stage of the tumor. The stages of oropharyngeal cancer span from Stage 0 to Stage IV, depending upon the size and location of the tumor (inside or outside of oropharynx or spread to lymph node and other tissues).

New treatments under development include various biologic therapies, such as vaccines, growth factor-receptor antagonists, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, and others, as well as photodynamic therapy. Vaccines, generally thought of as more prophylactic, are now being studied as a way to treat people with cancer by helping their immune system to recognize and attack the cancer cells.

We have a clinical trial open now of an HPV-16 therapeutic vaccine, said Dr. Gillison. Patients with a diagnosis of HPV-16 positive oropharyngeal cancer are eligible for vaccination after completing standard of care therapy. The vaccine is a naked DNA vaccine designed to augment the T-cell response to the virus. This trial is a phase I dose escalation and safety evaluation of four vaccinations administered over an 18-week period. Four out of a planned total of 16 patients have been enrolled.

A second therapeutic, peptide-based vaccine is also in clinical trial at the University of Maryland, said Duane A. Sewell, MD, Assistant Professor of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the University of Pennsylvania Health System in Philadelphia. In future trials, findings from the Yale study, indicating that the expression of the key HPV-related genes such as p16 affects prognosis in these patients, will have to be taken into account. Patients will be screened not only for HPV subtype, but also for p16, p53, and retinoblastoma expression.

Vaccine May Reduce Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence

Meanwhile, researchers are watching to see what happens with two prophylactic HPV vaccines for cervical cancers-one in the United States and one Europe-that are awaiting approval.

These HPV vaccines have received a great deal of national press recently, said Dr. Sewell. In clinical trials, they have been shown to prevent persistent infection of the genital mucosa by HPV; however the oropharyngeal mucosa was not examined. Further studies are warranted to determine the potential effects of these vaccines on oropharyngeal cancer, but it is within reason that these vaccines might also prevent HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

Hopefully, as these cervical cancer vaccines become more available and widely used, the secondary effect would be a decrease in the incidence of oropharyngeal cancer, said Dr. Sturgis.

In my practice, it is not unusual to see patients 30 to 40 years of age with advanced Stage III to IV disease. – -Maura L. Gillison, MD, PhD

Survival Rates Improving, More Research Needed

While the incidence of oropharyngeal cancer has remained stagnant for nearly 30 years, the good news is that survival rates have significantly improved in recent decades with the more widespread adoption of multidisciplinary care with radiation central to the treatment of oropharyngeal cancer. The prognosis for people with oropharyngeal cancer depends on the age and health of the person, disease stage, treatments used, and potentially the etiology of the disease.

In my practice, it is not unusual to see patients 30 to 40 years of age with advanced Stage III to IV disease, said Dr. Gillison. The critical piece of prognostic information, though, is the presence of high-risk HPV in the tumor (usually type 16) and not p16 as indicated in the Yale study, even after adjusting for age, lymph node status, and heavy alcohol consumption. An HPV-positive tumor translates to a 60% or greater reduction in death rates, according to Dr. Gillison’s research.

Uncertainty still exists though as most HPV-positive tumors occur in non-smoking patients, said Dr. Sturgis. I doubt that the HPV-positive prognostic factor plays as big a part as is suggested since it is confounded by the fact that patients who are non-smokers have been shown to have a better survival rate than smokers. Additionally, many studies have mixed two rather distinct groups (oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer patients) as well as other important differences. Research is still needed in this area for clarification.

Dr. Gillison said: My plan over the next five to ten years is to continue studying and gathering data on HPV and oropharyngeal cancers so that we can develop better screening and treatment strategies.

We are carefully studying the potential prognostic implications of HPV status of oropharyngeal cancers at a major cancer center and are attempting to develop HPV DNA as a biomarker for both disease extent and post-treatment monitoring, added Dr. Sturgis.

In the meantime, I think it is important for primary care physicians, ENTs, and public health workers to know that head and neck cancers do occur in younger patients who are non-smokers and non-drinkers, advised Dr. Gillison.

©2006 The Triological Society

Leave a Reply