INTRODUCTION

Bilateral vocal fold immobility can occur after iatrogenic injury, resulting in ankylosis of the cricoarytenoid joints, or can occur secondary to central nervous system insults, idiopathic and iatrogenic paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerves, or autoimmune disease. This often leaves patients with an untenable airway and may require a tracheostomy to bypass the upper airway obstruction.

Over the past several decades, there have been multiple attempts at surgical interventions to allow for breathing without the need for tracheostomy, with good success. Early attempts employed open techniques, and while these approaches were generally successful, they carried the morbidity often associated with open airway procedures.

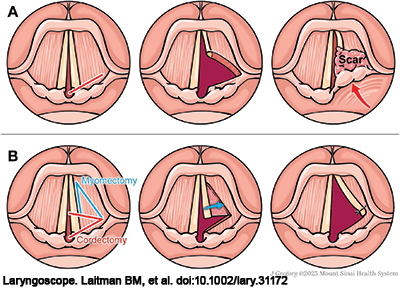

Figure 1. Traditional transverse cordotomy compared to TAM Cordotomy. (A) Traditionally, a transverse cordotomy is performed with an incision anterior to the vocal process taken laterally (left panel). While this can lead to initial release of the vocal fold and airway enlargement (middle panel), resultant granulation tissue and scarring can close this defect and bring the arytenoid forward once again, narrowing the airway (right panel). (B) In the TAM cordotomy, an additional anterior segment of muscle is resected (left panel) and the vocal fold mucosal flap is sutured laterally to the remaining lateral muscle border and false vocal fold (middle panel). This creates a triangular-shaped defect that is covered with mucosa, limiting restenosis (right panel).

Bilateral vocal fold fixation or paralysis (BVCP) can leave patients with an untenable airway and may require a tracheostomy to bypass upper airway obstruction. To improve the airway obstruction or in an effort to decannulate patients after tracheostomy, treatment for bilateral vocal fold immobility necessitates lasting airway dilation. Currently, BVCP is often treated by transoral CO2 laser-assisted transverse cordotomy, but this procedure can lead to subsequent scarring at the wound bed resulting in re-narrowing of the airway and poor voice (Figure 1A).

Here, we propose a modification of the transverse cordotomy procedure that improves predictable airway and voice outcomes.

METHOD

We report on a variation of the transverse cordotomy that is meant to improve healing and provide mucosal coverage, which combines the transverse cordotomy (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991. doi:10.1177/000348949110000905) with a thyroarytenoid myectomy (Rev Paul Med. 1985. PMID:4035182) (TAM). This procedure has been performed on a series of patients over the past 10 years.

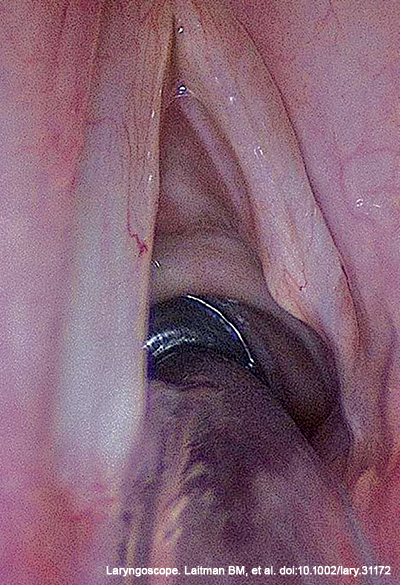

Figure 2. Surgical outcome of a patient five years after receiving a TAM cordotomy, showing a good triangular airway.

Endoscopic resection was done by CO2 laser microlaryngoscopy. Rather than resection of the membranous vocal fold, the transverse cordotomy was done as a straight but narrow laser cut at the vocal process, extended laterally into the vocalis and the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle. The cut was then followed by an anterior cordotomy lateral to the vocal ligament. This created an L-shaped mucosal flap that preserved the membranous vocal fold. A triangular wedge of TA muscle lateral to the vocal ligament and mucosal flap was liberally excised with the CO2 laser. The L-shaped mucosal flap consisting of the vocal ligament and the membranous vocal fold was then sutured using a 4–0 vicryl suture. The preserved mucosal flap moved laterally to cover the myectomy defect (Figure 1B).

RESULTS

The resection described creates a triangular-shaped defect that is covered with mucosa with an airway angle of 30 degrees. A video of the surgical procedure can be found online, with each of the four main steps of the procedure shown. The image in Figure 2 shows an example patient five years after such a resection, showing good triangular airway with adequate voice.

This technique was performed on 11 patients. Six patients had tracheostomies, and five of these patients were able to be decannulated. No frank aspiration was reported by any patient. All patients reported their voices as either “good” (6/11) or “fair” (5/11) after the procedure.

The modifications outlined in the TAM cordotomy can create the same initial airway opening provided by a traditional transverse cordotomy, but additionally can decrease the lateral bulk of the vocal fold through myectomy, and, through suture lateralization, allow for a smaller raw mucosal surface. This may promote faster healing and may limit scarring and restenosis. The TAM cordotomy seems to create a stable triangular-shaped glottis. In the surgeons’ opinions, these patients had a stable airway while preserving phonatory function. Although we have not systematically reviewed all TAM procedures done over the last 10 years, we continue to use this technique as first-line endoscopic treatment of patients with bilateral vocal fold paralysis and Type I or Type II posterior glottis stenosis.