INTRODUCTION

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) without esophageal atresia, also termed H-type, N-type, Gross type E, or isolated fistula, can be congenital or acquired. Children with H-type TEF typically present with cough during feeding, cyanotic spells, and recurrent pneumonia. Endoscopic repair of H-type TEF via bronchoscopy has traditionally been limited to long, narrow (<2 mm), recurrent TEFs, which often require multiple procedures with interposed material (i.e., fibrin glue) and the occasional addition of ancillary procedures such as an esophageal balloon or a biosynthetic mesh plug (J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:238-245. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24:510-515). Wide (>2 mm), short TEFs are notoriously difficult to repair endoscopically and have traditionally required a thoracoscopic or open approach (Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24:510-515).

We recently described suspending the esophagus with a laryngoscope to remove an intraluminal esophageal metal barbecue brush bristle in a child (Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E2066-E8). In that patient, the use of two hands under magnification with a wide field of view allowed the removal of a foreign body that would not have been accessible using a single instrument down a rigid esophagoscope. To our knowledge, suspension of the esophagus and the use of a microscope for endoscopic suture closure of a wide, short TEF have not previously been described. We report a patient for whom suspension microesophagoscopy was performed and describe how this approach allowed for improved management.

METHODS

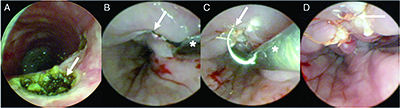

Figure 1. (A) Bronchoscopy demonstrating large, short tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) (arrow). (B) Suspension esophagoscopy setup using Weerda distending laryngoscope (*). (C) Endoscopic view of esophagus in suspension with Weerda laryngoscope (*) showing exposure of TEF (arrow).

A 15-year-old male with prior Gross type C TEF repair, short stature, scoliosis, subaortic stenosis resection, ventricular septal defect repair, gastroesophageal reflux, and asthma was intubated due to parainfluenza A pneumonia and rhabdomyolysis. After five weeks of ventilation with a cuffed endotracheal tube, a tracheostomy was performed, with insertion of a size 6 Shiley DCT (cuffed with inner cannula). He was decannulated, but persistent aspiration pneumonia prompted flexible fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopy, which revealed a left vocal cord paralysis. Rigid bronchoscopy revealed an A-frame tracheal deformity and a large (4-mm diameter), short TEF just distal to it in the lower half of the trachea, likely in the location of the previous TEF repair (Fig. 1 ). This was a defect in the common party wall rather than a tract. The patient was referred to otolaryngology because he and his parents did not want to undergo open TEF repair, and it was felt that another long general anesthetic would not be well tolerated given his medical status. After discussing the very low likelihood that traditional transtracheal endoscopic methods (i.e., cautery and Tisseel) could close the large TEF, and that his rapid desaturations and narrow trachea would not allow suture closure from the tracheal side, the possibility of experimental suspension esophagoscopy and endoscopic suture repair was offered, and the family consented to the procedure.

Figure 2. (A) Bronchoscopy demonstrating cauterization of tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) (arrow). (B) Esophagoscopy in suspension showing rigid suction catheter (*) used to deliver Bugbee cautery to TEF site (arrow). (C) Microlaryngeal needle driver (*) holding suture needle (arrow). (D) Sutured TEF from esophageal lumen (arrow).

The patient was intubated with a 4.5-mm cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) over a 4-mm telescope with cuff placed distal to the TEF. The esophagus was suspended with an adult Weerda distending operating laryngoscope (Fig. 1). A size 4 bronchoscope (Karl Storz, Germany) was inserted down the esophagus and through the TEF to ensure the ETT cuff was distal to the TEF. The FiO2 was decreased to 30%, and a Bugbee electrode cautery was placed down the side port of the bronchoscope to denude the edges of the TEF circumferentially on a setting of 15 W. Three 5-0 Vicryl sutures, 70-cm length on a TF needle (#J433), were placed using a Kleinsasser needle holder, microlaryngeal instruments, and a knot pusher (Karl Storz, Germany) to approximate the edges of the TEF. The procedure lasted approximately 1.5 hours. The patient was intubated with an endoscopically placed 5.5-mm cuffed ETT past the repair for the wakeup, sent to recovery extubated, and fed through his gastrojejunostomy tube.

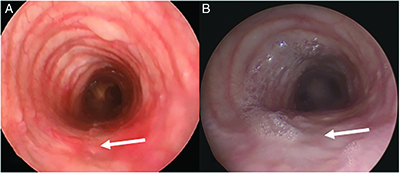

Figure 3. (A) Bronchoscopy demonstrating healed repair site after three months (arrow), and (B) after six months (arrow).

Despite the patient being asymptomatic, a persistent TEF was noted on the postoperative barium esophagram 18 days later. The decision was made to attempt closure for a second time by denuding the edges of the TEF more thoroughly and additionally on the tracheal side, and by placing more sutures than had previously been used. Rigid bronchoscopy was performed using a size 5 bronchoscope with 2.9 mm telescope. The tracheal surface of the TEF was cauterized using a Bugbee cautery down the side port on a setting of 30 W (Fig. 2). He was intubated over a telescope using a 5.0 cuffed ETT with the cuff placed distal to the TEF. The esophagus was suspended with an adult Weerda distending laryngoscope (Fig. 1). The FiO2 was decreased to 30%, and a Bugbee cautery was placed inside a rigid suction catheter that was bent to have a slight curve (Fig. 2). Delivering the Bugbee through the suction allows easier guidance, either through the tip for straight guidance or the velvet eye for curved guidance, and the ability to suction smoke for better visibility. This was placed down the esophagus under microscopic visualization, and the cautery was used on a setting of 30 W to denude the edges of the TEF circumferentially. Four 5-0 Vicryl sutures (#J433, 70 cm, TF needle) were placed from left to right with needle driver loaded backhand using microlaryngeal instruments and a knot pusher (Fig. 2). Repeat bronchoscopy was performed to ensure the ETT cuff had not inadvertently been sutured to the repair. The procedure lasted approximately two hours. The patient was extubated and sent to recovery in stable condition. Post-operative barium esophagram confirmed the TEF was closed six weeks later, and rigid bronchoscopy three and six months later during intubation for scoliosis repair confirmed a well-healed full-thickness repair (Fig. 3). Institutional research ethics board approval was waived for this case report.

CONCLUSIONS

Suspension microesophagoscopy in children can allow good visualization of the esophagus and a two-handed approach (four-handed if two surgeons) to facilitate closure of difficult-to-treat TEFs. TEF closure via the esophagus allows (1) access where suturing may not be possible in the smaller tracheal side, (2) intubation to prevent desaturation, (3) more time for the surgeon to accurately place sutures, (4) placement of knots in the esophageal lumen to decrease granulation tissue formation in the trachea. Further use of this exposure is required in younger children to determine if this technique is a viable alternative for endoscopic closure of difficult-to-treat H type TEF.