INTRODUCTION

In laryngeal surgery, resection of large neoplasms has traditionally required an open, transcervical approach. This approach requires a neck incision and laryngofissure in order to access the endolarynx. Advances in endoscopic techniques have minimized the need for an open neck surgery. Compared to traditional open surgery, endoscopic procedures are associated with less patient morbidity and shorter postoperative recovery.

Explore This Issue

September 2022Cricoid chondromas are benign growths that can result in dysphagia, dysphonia, and airway obstruction. These masses tend to be slow-growing, and patients can experience symptoms for several years before a diagnosis is made (Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:98–105; Ear Nose Throat J. 1996;75:540–544). Grossly, these masses are firm, smooth, calcified submucosal lesions. Surgery is the mainstay treatment for cricoid chondromas, and typically conservative, subtotal resection is recommended. Malignant transformation into chondrosarcoma is possible, which has metastatic potential depending on the grade of dedifferentiation.

The ultrasonic aspirator (UA) system is used as a surgical tool to resect rigid or calcified structures. This tool selectively debrides solid structures while simultaneously sparing surrounding, softer tissues. UA has not been frequently used in laryngeal surgery. Yawn et al. (Laryngoscope. 2016;126:941–944) reported using the UA system during endoscopic split of the posterior cricoid cartilage for patients with posterior glottic stenosis and an ossified cricoid cartilage. Daniero et al. (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:P200–P200) reported their findings with UA during four medialization thyroplasty window creations and two laryngofissure approaches. The authors found that the device is safe and requires a limited learning curve.

To our knowledge, UA has not been described as a tool for endoscopic removal of laryngeal chondroma. We present two cases of endoscopic removal of cricoid chondroma using the UA. This technique may have value since it allows the surgeon to debride large endolaryngeal masses while sparing delicate laryngeal structures and avoiding a transcervical surgical approach.

METHOD

Two patients who underwent transoral resection of cricoid chondroma using the UA system were retrospectively reviewed between 2018 and 2019. Indications for surgery, patient factors, and operative technique were collected. Pre- and post-procedure voice and swallowing indices were compared, including Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) and Eating Assessment Tool- 10 (EAT-10) scores.

TECHNIQUE

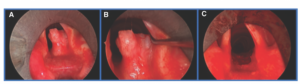

Figure 1.

(A) Transoral view of subglottic cricoid chondroma. (B) The mass was based off of the anterior face of the posterior cricoid abutting the medial portion of the right arytenoid cartilage. (C) After resection of the mass, there was significant improvement in the caliber of the airway.

The patients were positioned in a supine fashion and general anesthesia was induced. Jet ventilation through a Storz Dedo operating laryngoscope was used in patient 1, while patient 2 was intubated transorally using a laser-safe endotracheal tube. A suspension microlaryngoscopy surgical approach was used. In patient 2, the overlying mucosa was incised using a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. The UA blade cost was approximately $500 (Sonopet, Stryker Corp, Model #5450 820 302). The extended-length angled handpiece and console (Sonopet, Stryker Corp, Model #:5450 820 000) costs were $15,000 and $85,000, respectively. This equipment had been routinely used by other specialties, including neurosurgery. Thus, these highlighted cases did not require special equipment purchasing.

The device was introduced through the lumen of the laryngoscope and the chondroma was resected. Resection setting was as follows: power at 100%, suction at 100%, and irrigation at 15 ml/min. In both cases, the majority of chondroma resection was performed by a single surgeon holding the UA in one hand and a 0-degree telescope in the other. The operating microscope was used intermittently when a bimanual technique was needed (e.g., laser cuts, suturing). A specimen was sent for pathology. The entirety of the visible mass was resected, and no cases required conversion to an open approach. Following resection, the overlying mucosa was reapproximated using a transoral suturing technique in patient 2. Patient 1 required no mucosal sutures given the minimal degree of mucosal violation. Both patients were discharged on postoperative day one. The key steps from Patient 1’s surgery are included in video format (see supporting video).

RESULTS

Postoperatively, there were no adverse events, and patients resumed an oral diet. Both patients reported subjective improvement in voice and swallowing complaints.