Introduction

Anterior glottic webs are abnormal fusions of the anterior vocal folds that may be congenital or acquired. Congenital anterior glottic webs are rare and result from failure of recanalization of the larynx during development. Acquired anterior glottic webs are more common and typically occur due to trauma or inflammation of the larynx (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2013;122:672-678).

The treatment of anterior glottic webs is primarily surgical and can be performed by endoscopic or open approaches. Endolaryngeal procedures are preferred because they are less invasive and have lower morbidity. Endoscopic techniques involve either mucosal flap elevation with suture stabilization or incision of the web with stent placement (ibid).

Standard endoscopic stent placement techniques involve sutures placed with either a specialized needle carrier or microlaryngoscopic instruments. In practice, this placement can be difficult because most operating rooms are not equipped with a specialized needle carrier created for this purpose. In addition, it is difficult to pass sutures endoscopically from the laryngeal lumen out of the anterior neck when working in the tight surgical field of a laryngoscope. Finally, regardless of the technique used, there are issues of skin breakdown and scar formation at the site of the stabilizing suture on the anterior neck skin and the need for a second general anesthesia to remove the stent.

Method

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia using a Dedo-Pilling Micro-Laryngoscope with the patient in suspension. The web is incised using a CO2 laser. A modified ruler is used to measure the vertical length of the web and serve as a template for the stent. Reinforced silicone sheet with 0.007-inch thickness is used to prepare the keel stent. A 3–0 polypropylene suture is then passed along what will become the anterior edge of the keel as it sits in the airway.

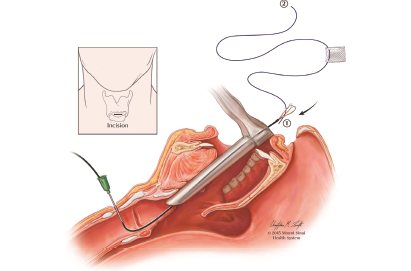

Next, a horizontal 1-cm skin incision is made at the level of cricothyroid membrane. This incision allows all the stabilizing sutures to be placed subcutaneously, thus obviating issues of skin breakdown secondary to the traditional technique of tying the suture on the anterior neck over a bolster or button. An 18- or 20-gauge intravenous catheter is passed through the midline of the cricothyroid membrane into the subglottis under endoscopic vision. The needle is withdrawn, leaving the polymer sheath in place (Fig. 1). During the venous catheter placement, the endotracheal tube balloon is deflated or moved distally; extra care should be taken not to perforate it. A renal stone extractor is then introduced into the endolarynx through the catheter sheath and pulled superiorly through the laryngoscope using alligator forceps. The end of the suture attached to the inferior aspect of the keel is passed into the stone extractor basket, which is then closed, securing the suture. The stone extractor is pulled out from the cricothyroid incision site, pulling the suture along.

Fig. 1. Passing an intravenous catheter through a 1-cm skin incision over the cricothyroid membrane into the subglottis and retrieving the inferior suture end using the renal stone extractor

A second venous catheter is bent slightly and then passed through the thyrohyoid membrane, entering the airway at the petiole of the epiglottis in a technique similar to that used during in-office vocal fold injections. No skin incision is required at this site. Again, the needle is withdrawn, leaving the polymer sheath in place. The same stone extractor is then introduced into the endolarynx through this superior catheter and pulled-out laryngoscope. The superior end of the suture is secured by the stone extractor basket and pulled out of the anterior neck skin through the thyrohyoid membrane catheter site. The catheters are removed, and then the keel is grasped with alligator forceps and guided into the site of the incised web as both external suture ends are pulled away from the neck until tight. The superior end of the suture is then attached to a free needle. This needle carries the suture subcutaneously as it is passed from the superior puncture site to the inferior incision site. The suture is then tied down on the tissue beneath the skin incision site while ensuring proper placement of the keel in the airway. The 1-cm skin incision is then closed.

In the immediate postoperative period, patients are given no specific restriction or care needs beyond keeping the skin incision dry for three days. Voicing is allowed without any restriction beyond decreasing voice use with evidence of strain or fatigue.

Three weeks after the surgery, the keel can be removed. Instead of removing the keel in the operating room under general anesthesia, this can be done in the office with topical anesthesia. The airway is anesthetized with an injection of 2 cc of 4% lidocaine into the airway via the cricothyroid membrane. The previous skin incision at the level of cricothyroid membrane is opened, and the keel suture is identified. Using a channeled laryngoscope or esophagoscope, the keel is grasped with cupped forceps. The suture is released and removed. Simultaneously, the keel is removed as the scope is pulled back out of the nostril with the keel held by the cupped forceps. The skin incision is neatly sutured closed.

Instead of removing the keel in the operating room under general anesthesia, this can be done in the office with topical anesthesia.

Results

Six patients on whom the renal basket technique was utilized between 2014 to 2019 were included. All patients had preoperative complaints of dysphonia, especially decreased projection and vocal strain. There were no complaints of dyspnea. All patients had better voice function with increased projection, decreased vocal strain, and fatigue after stent removal. Although the voices became less raspy, none returned to normal. One patient had a mild amount of granulation at the anterior aspect of the stent, which resulted in mild to moderate dysphonia while the stent was in place. This resolved soon after stent removal. No patients have reported significant complications or recurrence.