INTRODUCTION

Nasopharyngectomy can be used as a salvage surgery to remove residual or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinomas (rNPC) after radiotherapy and is associated with improved local control and increased overall survival compared to reirradiation alone (World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;1:34–43; Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:1141–1154). The proximity of the nasopharynx to the skull base and critical anatomic structures, however, particularly the internal carotid artery (ICA), makes surgical resection of the nasopharynx challenging. To access these tumors, transfacial and transcervical corridors have been described, most notably through a maxillary or mandibular swing or endoscopic endonasal approach (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7:425–432).

The maxillary swing is a well-described approach that involves facial translocation through Le Fort I osteotomies and allows access to the nasopharynx and parapharyngeal space through the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus for en bloc resection. Although this approach results in better survival rates, there are risks of infraorbital nerve injury, facial numbness, trismus, palatal fistula, osteonecrosis, and difficulty accessing and protecting the ICA (World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;1:34–43).

Although a transcervical or transfacial approach affords maximal access to the nasopharynx, it has high postoperative morbidity. Endoscopic nasopharyngectomy provides minimally invasive access and is considered by many to be the preferred surgical treatment for rNPCs when feasible based on tumor anatomy and surgeon skill. Optical telescopes offer improved visualization of the nasopharynx compared to open approaches and allow for closer visualization of tumor margins. Using expanded endoscopic techniques, many tumors can be accessed using an endonasal approach with significantly reduced morbidity. Despite this access, identification of the parapharyngeal ICA remains challenging, as direct visualization is hindered by soft tissue and tumor. To mitigate these issues, we describe a method of combining a lateral transcervical approach, to provide proximal ICA control and early visualization without the morbidity of a maxillary swing, with the endonasal endoscopic approach, allowing two teams to work concurrently and more expeditiously with improved ICA management and sound oncologic control of the tumor laterally at the Eustachian tube and parapharyngeal space.

METHOD

A retrospective case series of patients with nasopharyngeal malignancies who underwent combined open lateral approach and endoscopic transnasal nasopharyngectomy was performed. Patients were included if they underwent a combined approach for resection of nasopharyngeal tumor and excluded if they underwent endoscopic resection without a simultaneous lateral approach. Data were collected on three males with rNPC and two females with adenoid cystic carcinoma. A cadaveric dissection was also performed to demonstrate the approach and identify relevant anatomy.

Surgical Technique

A combined transcervical and endoscopic endonasal approach to access the infratemporal fossa and parapharyngeal space was performed in all patients. A modified preauricular/transcervical incision was designed. The facial nerve was kept within the parotid parenchyma and elevated along with the parotid tail, rather than identifying the nerve and potentially creating a stretch injury from retraction on an unprotected nerve. The stylomandibular ligament was transected and the styloid process removed to the skull base, taking care to gently elevate the parotid in this area to protect the facial nerve within the parenchyma. Anterior retraction or ligation of the external carotid artery was performed to open the post-styloid parapharyngeal space. The ICA was identified, along with the glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves.

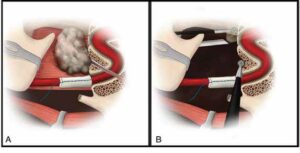

Next, the nasopharynx musculature, including the superior constrictor and Eustachian tube complex, were identified anteromedial to the great vessels. We dissected the previously identified ICA and nerves to the level of the skull base, while identifying signs of tumor involvement. At the level of the carotid canal, a 3-in. Cottonoid was placed medial to the carotid artery to provide a visual cue and protection during subsequent endonasal tumor dissection (Figure 1). With the ICA identified, protected, and lateralized relative to the tumor, endonasal endoscopic tumor dissection was conducted via a transpterygoid approach to access the pterygomaxillary and infratemporal fossae. We accomplished this by performing a medial maxillectomy followed by identification and ligation of the sphenopalatine artery.

Figure 1. (A) Styloid ligament has been transected and a Cottonoid pledget placed on the internal carotid artery for protection during tumor resection. The tumor lies in the nasopharynx, obstructing the Eustachian tube. (B) Endoscope and instrument accessing nasopharynx via the nares with additional instruments entering nasopharynx via the lateral, transcervical access.

Then, the pterygoid plates were identified and resected for access to the anteromedial boundaries of the tumor. The pterygomaxillary fissure was then resected. The posterior extent of dissection was dictated by tumor involvement. After endonasal mucosal cuts were completed, the superior constrictor attachments to the skull base were released from both the endonasal and lateral approach, revealing the foramen lacerum and foramen ovale. The endonasal tumor dissection ultimately communicated with the cervical incision around the specimen, and either the endonasal or the cervical access could be used to complete tumor extirpation. With the carotid canal and foramen lacerum in full view, we were able to transect the Eustachian tube using the lateral approach as it entered its bony canal. In all cases, either reconstruction with regional pedicled flap or free tissue transfer was used to close the nasopharyngeal defect (see the supporting video).

RESULTS

Five patients underwent the combined approach surgery between March 2019 and October 2021. Patients 1–3 and 5 received definitive chemoradiotherapy to the skull base. Pathological examination of the surgical specimens confirmed that tissue margins were free of disease, except for patient 5. The mean operative time was 13 hours.

Patients 1, 3, and 4 had uncomplicated postoperative courses. Patient 2 had vocal cord paresis secondary to surgical manipulation at the time of resection that subsequently resolved without any intervention. Patient 5 required return to the OR for hematoma evacuation one day after surgery. There were no cerebrospinal fluid leaks, flap failures, or meningitis. The mean follow-up time was 15.1 months, with no evidence of tumor recurrence in all patients.