INTRODUCTION

Submandibular salivary stones located in more proximal portions of the submandibular duct or within the gland have historically been managed by removing the entire submandibular gland; however, as gland-sparing techniques have risen in favor, treatment is often sialendoscopy or transoral sialolithotomy under general anesthesia. For larger stones, transoral sialolithotomy is preferred over sialendoscopy (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:553-565). Management of sialolithiasis via transoral sialolithotomy has been shown to result in improved parenchymal changes, recanalization of Wharton’s duct, and improvements in quality of life (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:553-565; Ear Nose Throat J. 2019;98:287-290; Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280:5031-5037).

There have been increasing efforts across otolaryngology to perform in-office procedures with local anesthesia. Benefits include reducing the time and economic costs imposed on patients, as well as avoiding the inherent risks of general anesthesia (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:255-260; Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43:103424). For distal or mid-ductal stones, transoral sialolithotomy under local anesthesia is routinely performed; however, hilar or intraglandular stones have traditionally required general anesthesia for removal (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:553-565; Ear Nose Throat J. 2019;98:287-290; Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280:5031-5037). This case series aims to showcase the efficacy and efficiency of in-office transoral submandibular sialolithotomy for hilar and intraglandular stones. This novel practice, unique to the senior author (A.J.), has the potential to minimize costs and risks associated with traditional sialolithotomies under general anesthesia.

METHODS

Design and Subjects

A retrospective chart review was conducted for patients who underwent in-office transoral sialolithotomy for hilar or intraglandular sialoliths by the senior author (A.J.) from January 2020 to July 2022. A total of 40 patients met these criteria. Each chart was reviewed to determine patient demographics, sialolith size and laterality, procedure success, and associated complications. This investigation was deemed exempt from the George Washington University institutional review board review (NCR224117).

Initial Evaluation and Patient Selection

In-office transoral sialolithotomy is offered to practically all patients with a localizable, accessible stone identified on ultrasound performed during initial evaluation. Cases in which patients are not offered this procedure are largely based on the size and location of the sialolith. In patients with small, 1–2-mm intraglandular stones or, conversely, extremely large stones greater than 4 cm that replace the gland, this technique is not indicated. In the senior author’s experience, all stones greater than 4 cm, irrespective of the location, are unlikely to be amenable to transoral removal due to adhesion to the salivary gland. Ultrasound localization can help identify if a transoral approach is feasible, especially when determining the depth of the stone within the submandibular gland, as deeper stones are less likely to be successfully removed transorally. Additionally, eliciting a dental history or a prior experience with transoral procedures under local anesthesia can be helpful in predicting a patient’s tolerance of an in-office transoral sialolithotomy.

Surgical Technique

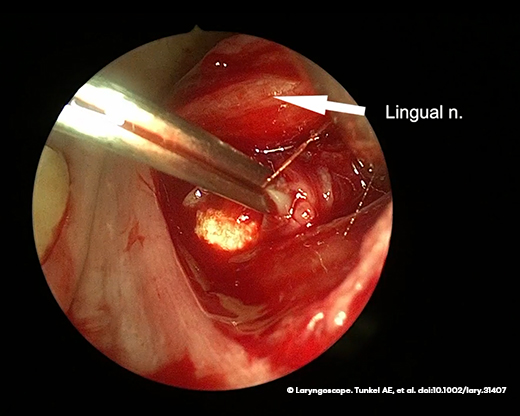

Figure 1. An image from a video demonstrating in-office transoral hilar sialolithotomy showing the stone before extraction.

Informed consent is obtained for all patients. A sweetheart retractor or wooden tongue depressor is utilized to retract the tongue and expose the floor of the mouth. The sialolith is localized using a combination of palpation and ultrasound. Approximately 3 mL of local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine) is injected submucosally into the floor of the mouth to provide anesthesia and accomplish hydrodissection of the superficial tissues. A number 15 scalpel blade is then utilized to make a mucosal incision, and blunt dissection is performed. Care is taken to identify the lingual nerve and mobilize it medially, retracting the nerve away from the field so it remains protected. Lateral and deep to the lingual nerve and deep to the mylohyoid fibers, the submandibular duct and the calculus are identified. The distal-most aspect of the submandibular duct is grasped with forceps, and a scalpel is used to incise the duct in a parallel fashion. Blunt dissection with tenotomy scissors is then used to confirm identification of the sialolith (Figure 1).

Once the stone is retrieved with a curved clamp, ultrasound is performed to confirm no further presence of sialoliths. If the dochotomy is greater than 1 centimeter in length, a sialodochoplasty is then performed. Two 4–0 chromic gut sutures are placed in a simple interrupted fashion to suture the inside of the duct to the posterior floor of the mouth mucosa, marsupializing the duct. A lacrimal probe is placed in the ductal lumen to confirm ductal patency. After the procedure, the patient is instructed to frequently massage the gland to promote salivary flow. They are also encouraged to stay adequately hydrated and use sialogogues if necessary. Patients return for follow-up after one week to ensure ductal patency.

RESULTS

A total of 40 patients met inclusion criteria for this review, having undergone an in-office transoral sialolithotomy for intraglandular or hilar stones between January 2020 and July 2022. Of these patients, 19 were female (47.5%) and 21 were male (52.5%). The average age was 52.8 years. Laterality of stones was relatively balanced, with 21 patients presenting for left-sided symptoms (52.5%) and 19 with right-sided symptoms (47.5%). A total of 55 stones were removed; 94% of removed stones were hilar or intraglandular. On average, patients had 1.45 ± 0.72 stones removed, with a mode of one stone removed per patient. The average stone size was 0.98 ± 0.54 centimeters in the greatest dimension.

Of the 40 attempted in-office sialolithotomies, 36 (90%) were successful. Failure to complete the procedure was due to a vasovagal reaction during the procedure (1), stone adherence to the submandibular duct or gland (2), or poor visualization secondary to patient anatomy (1). Two patients ultimately underwent transoral excision under general anesthesia (Table 1). Only two complications were reported: one patient with temporary lingual nerve paresis and a second with a postoperative intraglandular abscess. Only three (8%) patients experienced recurrence of salivary stones after the in-office procedure.