Patient engagement has become something of a buzzword in clinical care, a phrase increasingly used over the past decade to basically describe getting patients involved in their own care to improve health outcomes. Like the phrase “evidence-based medicine” years ago or, more recently, “big data,” the phrase “patient engagement” has entered the clinical lexicon with some ease, but its full meaning continues to unfurl with a deeper understanding of what engaging patients in their own care looks like and how this is distinguished from other patient-centered foci such as “patient satisfaction” and “patient experience.”

In 2019, Marisa A. Ryan MD, MPH, and Emily F. Boss, MD, MPH, gave some flesh to this phrase in an article entitled “Patient Engagement in Otolaryngology,” (Otolaryngol Clin North Amer. 2019;52:23-33) in which they discuss important ways to promote patient engagement through information technology (e.g., patient portals for access to prescribed medications, appointments), patient-centered communication (e.g., using clear, jargon-free language), and shared decision-making (e.g., incorporating patient/family preferences and values) and the subsequent improvement these measures can have on patient safety. Senior author Dr. Boss, professor in the departments of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, pediatrics, and health policy & management at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, emphasized that “the more engaged patients are in their care, the more they trust their clinicians, perceive respect from their clinicians, and adhere to treatment plans, which, in turn, improves outcomes and reduces attrition and loss to follow-up.”

Facilitating patient engagement can take many forms. Among them is the use of phone-based technologies that can make it easier for patients and providers to communicate on a variety of issues, ranging from routine setting up for and reminding patients of clinical visits to more novel uses that facilitate intervention for specific conditions.

Phone-Based Technologies in Otolaryngology

In a recent review of smartphone applications (apps), Eleonora M.C. Trecca, MD, an otolaryngologist in the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Research Hospital Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo (Foggia), Italy, and her colleagues systematically reviewed apps used in otolaryngology for screening, early diagnosis, and management of their otolaryngologic conditions (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130:78-91). A total of 1,074 otolaryngologic apps were found through a search of the Google Play Store, Apple App Store, and PubMed. Table 1 lists the apps grouped by their use per subspecialty.

Given the ubiquity of smartphones and the increasing availability and use of apps for otolaryngologic conditions, Dr. Trecca, lead author of the study, thinks otolaryngologists need proper training in how to choose and use these apps. Training is particularly needed, she said, because of the high variability in the quality of these apps, most of which are developed without help from healthcare professionals or scientific societies.

A main limitation of these apps, as found in the study, is the lack of validation by clinical trials. In addition, most apps receive only minimal regulation by the Food and Drug Administration because regulation applies only to apps categorized as “medical” and not to those categorized as “lifestyle.” Dr. Trecca also cautioned against viewing popular or widely used apps as a criterion for quality, as the study found that higher-quality apps often received fewer reviews and downloads than popular, but low-quality, apps.

The more engaged patients are in their care, the more they trust their clinicians, perceive respect from their clinicians, and adhere to treatment plans, which, in turn, improves outcomes and reduces attrition and loss to follow-up. —Emily F. Boss, MD, MPH

Despite these limitations, she sees the potential benefit of the apps given sufficient education on their quality. “Their application in the clinical practice can bring enormous advantages in diagnosis and treatment of ENT disease, especially in rural and underserved areas,” Dr. Trecca said.

Phone-Based Surgical Reminders

Drilling down deeper, there are some novel uses of phone-based technology that can enhance patient engagement in otolaryngologic practice.

For the many patients who undergo surgical procedures for otolaryngologic conditions, the use of an app to remind them to adhere to surgical protocols both prior to and after surgery can help reduce or avoid altogether the need to reschedule surgery and can potentially lead to improved patient outcomes.

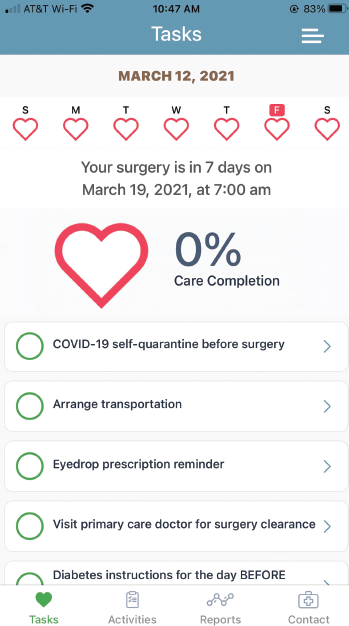

Michael R. Holtel, MD, past chair of the AAO–HNS telehealth committee and an otolaryngologist at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego, Calif., who published an early article on cell phones in otolaryngology (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:1351-1358), is working on adapting an app for managing ophthalmology surgical patients. Developed by a Sharp Healthcare team led by his ophthalmologist colleague Tommy Korn, MD, the app moves a patient through the surgical process beginning with a checklist for reminders on what patients need to do prior to surgery (e.g., when to stop eating, setting up transportation). After surgery, the app provides instructions about what patients need to do for postop care, records their medication use, and also includes a way for patients to send photos of their incisions back to the surgeon for review (Figure 1).

The cell phone is often the connecting device that allows us to monitor our patients and intervene at the optimal time while avoiding the need for repeated return clinic visits. —Michael R. Holtel, MD

“Many physician offices use text appointment reminders, but this app provides a more detailed and interactive approach,” said Dr. Holtel, who underscored the utility of the app for both the provider, by reducing the need to cancel surgeries when patients forget to adhere to presurgical protocols, and for the patient, by making it easier to follow surgical protocols.

Based on ophthalmology experience with the app, Dr. Holtel thinks a similar app tailored to otolaryngologic patients will provide similar benefits. Current data on its use in over 300 cataract patients show a lower rate of surgical cancellations. Although no published data are yet available on the app’s effect on postsurgical care, Dr. Holtel said that he thinks the ability to constantly monitor a patient via postsurgical follow-ups will improve care.

He noted that constant monitoring of wearable devices with the addition of machine learning is where medicine, including otolaryngology, is headed. “The cell phone is often the connecting device that allows us to monitor our patients and intervene at the optimal time while avoiding the need for repeated return clinic visits,” he said.

Phone-Based Intervention for Insomnia

Figure 1. A screen shot of the SHARP help companion app currently used in ophthalmology. Dr. Holtel is adapting the app to his otolaryngologic practice by using the APPLE CareKit (www.researchandcare.org/carekit).

Insomnia is among the sleep conditions that clinicians, including otolaryngologists, routinely see in clinical practice. Along with significantly affecting a patient’s quality of life, insomnia often co-occurs with chronic diseases and can disrupt sufficient management of these conditions.

Cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is recommended as first-line treatment of chronic insomnia by the American College of Physicians (Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133. doi:10.7326/M15-2175). The treatment works by helping patients to identify feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that contribute to insomnia (CBT-I. Sleep Foundation. Updated October 22, 2020).

Access to CBT-I, however, can be limited for many patients. “CBT-I isn’t readily available, particularly in rural and medically underserved populations,” said Susan M. McCurry, PhD, research professor in child, family, and population health at the University of Washington School of Nursing in Seattle. “Demonstrating that CBT-I could be effectively delivered via the telephone would potentially lead to improved access for this treatment.”

In a recently published study, Dr. McCurry and her colleagues evaluated the effectiveness of phone-based CBT-I in older adults with comorbid insomnia and moderate to severe osteoarthritis pain. Published in 2021 in JAMA Internal Medicine, the study included 327 patients (>60 years of age) randomized to phone-based CBT-I (n=163) versus an education-only control (EOC) group (n=164). Patient recruitment was done through Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPW) between 2016 and 2018, and potential patients were identified through the KPW electronic health records (JAMA Intern Med [published online ahead of print February 22, 2021]:e209049).

Patients in both groups participated in phone-based interventions that consisted of six sessions over eight weeks. Each session lasted up to, but no more than, 30 minutes with a trained sleep coach (psychologist, nurse, or social worker). Patients in the CBT-I group received instruction on sleep restriction and sleep hygiene, as well as cognitive strategies to reduce hyperarousal at night and address unrealistic sleep expectations. Patients in the EOC group received information about insomnia in a nondirective format. Both groups kept sleep diaries.

Patients were assessed at two and 12 months following intervention. At both time periods, patients treated in the CBT-I group reported significant and clinically meaningful improvements in sleep compared to the EOC group. Patients in the CBT-I group reported a significant decrease in insomnia severity at two months compared to the EOC group (decrease of 8.1 points vs. 4.8 points, respectively; adjusted mean difference of -3.5 points; P<.001). At 12 months, patients in the CBT-I group continued to have a significant reduction in insomnia severity compared to the EOC group (adjusted mean difference of -3.0 points; P<.001). Overall, 67 of 119 (56.3%) patients in the CBT-I group remained in remission at the 12-month follow-up compared to 33 of 128 (25.8%) in the EOC group. According to Dr. McCurry, these results are comparable to those found when CBT-I is done in person.

Table 1. Main Otolaryngologic Apps Grouped by Subspecialty

| Subspecialty | Number of Apps | Type of Apps (used for) |

|---|---|---|

| Audiology | 128 (Android) 106 (iOS) | • Audiograms • Hearing aids—those that use headphones connected to a smartphone to filter and amplify speech |

| Tinnitus and Balance | 78 (Android) 77 (iOS) | • Tinnitus management • Balance diagnosis |

| Sleep Medicine | 145 (Android) 177 (iOS) | • Recording and analyzing sleep patterns (and, in some apps, tracking body movement during sleep) |

| Rhinology | 175 (Android) 155 (iOS) | • Support management of pathology • Provide real-time weather and/or alerts to rising pollen levels |

| Laryngology and Voice Therapy | 20 (Android) 13 (iOS) | • Aid for patients with tracheostomy, aphasia, or other speech/neurological disorder affecting communication. |

Source: Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130:78-91

Fatigue was also significantly reduced in the CBT-I group compared to the EOC group at two months (mean difference of -2.0; P<.001) and 12 months (mean difference of -1.8 points; P<.003). Patients in the CBT-I group also reported reduced pain scores at two months, but this was not sustained at 12 months.

Based on these results, Dr. McCurry encourages clinicians to use phone-based CBT-I given the high rates of prevalence and the restricted access to in-person CBT-I. “If people had greater access to CBT-I, it could potentially improve quality of life for many individuals,” she said.

Other investigators looking at a wider use of phone-based CBT-I, including fully automated digital CBT, as well as the provider-guided version used in the above study, have demonstrated an improvement in quality of life of patients using this technology.

In a study published in 2019, Colin A. Espie, PhD, and his colleagues reported that patients with insomnia treated with a fully automated digital CBT (dCBT) program (Sleepio) showed improvement in functional health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:21-30). The study included 1,711 patients with insomnia randomized to dCBT (n=853) or sleep hygiene education (SHE) (n=858). Patients in the dCBT group received CBT training over six sessions lasting about 20 minutes each for up to 12 weeks through the Sleepio web-based program or an associated iOS app. Patients in the SHE group received routine care consisting of education regarding sleep hygiene. (Dr. Espie reports a licensed patent from Sleepio and is the co-founder and CMO of Big Health, Ltd.)

At weeks four, eight, and 24, patients in the dCBT group showed a significant improvement in sleep-related quality of life compared to the SHE group (-8.76, -17.60, and -18.72, respectively), with a small improvement in functional health (adjusted difference of 0.90, 1.76, and 1.76, respectively) and psychological well-being (adjusted difference of 1.04, 2.68, and 2.95, respectively). Improvements in insomnia found at four and eight weeks mediated the improvements seen at eight and 24 weeks, respectively, in sleep-related quality of life, functional health, and psychological well-being.

“This is a great study for a couple of reasons,” said Jennifer Kanady, PhD, lead clinical innovator for Sleep Big Health (the maker of Sleepio program). “First, this study demonstrated that digital CBT not only improves nighttime symptoms of insomnia but also improves daytime functioning as well … and, second, the benefits of digital CBT on daytime functioning were maintained four months after discontinuing treatment.” Additionally, she said that the positive results appear to hold up well in more general samples of patients, as many of the people in the study had mental or physical health comorbid conditions.

A 2017 review of dCBT for insomnia provides a comprehensive examination of the technology, including provider-guided dCBT and fully automated dCBT, along with a discussion that answers commonly asked questions about subjects such as its cost-effectiveness and the demographic and clinical predictors of improvement with dCBT (Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2017;3:48-56).

One caveat when using dCBT with patients who have sleep apnea, Dr. Kanady underscored, is the need to address the sleep apnea to improve efficacy of CBT for insomnia. “While digital CBT for insomnia is likely effective for those with both insomnia and sleep apnea, those with untreated sleep apnea will still experience daytime symptoms, such as excessive daytime sleepiness, and would benefit more from digital CBT once the sleep apnea has been properly addressed,” said Dr. Kanady.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.