Phone-Based Intervention for Insomnia

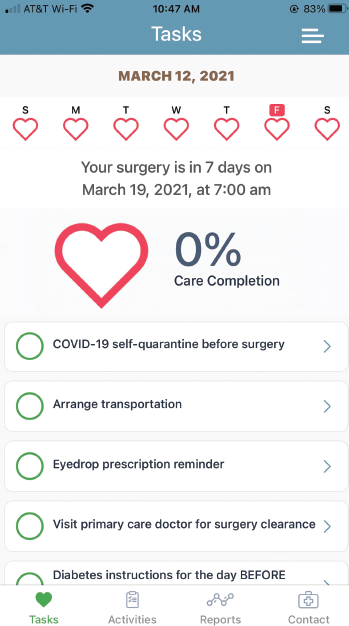

Figure 1. A screen shot of the SHARP help companion app currently used in ophthalmology. Dr. Holtel is adapting the app to his otolaryngologic practice by using the APPLE CareKit (www.researchandcare.org/carekit).

Insomnia is among the sleep conditions that clinicians, including otolaryngologists, routinely see in clinical practice. Along with significantly affecting a patient’s quality of life, insomnia often co-occurs with chronic diseases and can disrupt sufficient management of these conditions.

Explore This Issue

June 2021Cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is recommended as first-line treatment of chronic insomnia by the American College of Physicians (Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133. doi:10.7326/M15-2175). The treatment works by helping patients to identify feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that contribute to insomnia (CBT-I. Sleep Foundation. Updated October 22, 2020).

Access to CBT-I, however, can be limited for many patients. “CBT-I isn’t readily available, particularly in rural and medically underserved populations,” said Susan M. McCurry, PhD, research professor in child, family, and population health at the University of Washington School of Nursing in Seattle. “Demonstrating that CBT-I could be effectively delivered via the telephone would potentially lead to improved access for this treatment.”

In a recently published study, Dr. McCurry and her colleagues evaluated the effectiveness of phone-based CBT-I in older adults with comorbid insomnia and moderate to severe osteoarthritis pain. Published in 2021 in JAMA Internal Medicine, the study included 327 patients (>60 years of age) randomized to phone-based CBT-I (n=163) versus an education-only control (EOC) group (n=164). Patient recruitment was done through Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPW) between 2016 and 2018, and potential patients were identified through the KPW electronic health records (JAMA Intern Med [published online ahead of print February 22, 2021]:e209049).

Patients in both groups participated in phone-based interventions that consisted of six sessions over eight weeks. Each session lasted up to, but no more than, 30 minutes with a trained sleep coach (psychologist, nurse, or social worker). Patients in the CBT-I group received instruction on sleep restriction and sleep hygiene, as well as cognitive strategies to reduce hyperarousal at night and address unrealistic sleep expectations. Patients in the EOC group received information about insomnia in a nondirective format. Both groups kept sleep diaries.

Patients were assessed at two and 12 months following intervention. At both time periods, patients treated in the CBT-I group reported significant and clinically meaningful improvements in sleep compared to the EOC group. Patients in the CBT-I group reported a significant decrease in insomnia severity at two months compared to the EOC group (decrease of 8.1 points vs. 4.8 points, respectively; adjusted mean difference of -3.5 points; P<.001). At 12 months, patients in the CBT-I group continued to have a significant reduction in insomnia severity compared to the EOC group (adjusted mean difference of -3.0 points; P<.001). Overall, 67 of 119 (56.3%) patients in the CBT-I group remained in remission at the 12-month follow-up compared to 33 of 128 (25.8%) in the EOC group. According to Dr. McCurry, these results are comparable to those found when CBT-I is done in person.

Table 1. Main Otolaryngologic Apps Grouped by Subspecialty

| Subspecialty | Number of Apps | Type of Apps (used for) |

|---|---|---|

| Audiology | 128 (Android) 106 (iOS) | • Audiograms • Hearing aids—those that use headphones connected to a smartphone to filter and amplify speech |

| Tinnitus and Balance | 78 (Android) 77 (iOS) | • Tinnitus management • Balance diagnosis |

| Sleep Medicine | 145 (Android) 177 (iOS) | • Recording and analyzing sleep patterns (and, in some apps, tracking body movement during sleep) |

| Rhinology | 175 (Android) 155 (iOS) | • Support management of pathology • Provide real-time weather and/or alerts to rising pollen levels |

| Laryngology and Voice Therapy | 20 (Android) 13 (iOS) | • Aid for patients with tracheostomy, aphasia, or other speech/neurological disorder affecting communication. |

Source: Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130:78-91

Fatigue was also significantly reduced in the CBT-I group compared to the EOC group at two months (mean difference of -2.0; P<.001) and 12 months (mean difference of -1.8 points; P<.003). Patients in the CBT-I group also reported reduced pain scores at two months, but this was not sustained at 12 months.

Based on these results, Dr. McCurry encourages clinicians to use phone-based CBT-I given the high rates of prevalence and the restricted access to in-person CBT-I. “If people had greater access to CBT-I, it could potentially improve quality of life for many individuals,” she said.

Other investigators looking at a wider use of phone-based CBT-I, including fully automated digital CBT, as well as the provider-guided version used in the above study, have demonstrated an improvement in quality of life of patients using this technology.

In a study published in 2019, Colin A. Espie, PhD, and his colleagues reported that patients with insomnia treated with a fully automated digital CBT (dCBT) program (Sleepio) showed improvement in functional health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:21-30). The study included 1,711 patients with insomnia randomized to dCBT (n=853) or sleep hygiene education (SHE) (n=858). Patients in the dCBT group received CBT training over six sessions lasting about 20 minutes each for up to 12 weeks through the Sleepio web-based program or an associated iOS app. Patients in the SHE group received routine care consisting of education regarding sleep hygiene. (Dr. Espie reports a licensed patent from Sleepio and is the co-founder and CMO of Big Health, Ltd.)

At weeks four, eight, and 24, patients in the dCBT group showed a significant improvement in sleep-related quality of life compared to the SHE group (-8.76, -17.60, and -18.72, respectively), with a small improvement in functional health (adjusted difference of 0.90, 1.76, and 1.76, respectively) and psychological well-being (adjusted difference of 1.04, 2.68, and 2.95, respectively). Improvements in insomnia found at four and eight weeks mediated the improvements seen at eight and 24 weeks, respectively, in sleep-related quality of life, functional health, and psychological well-being.

“This is a great study for a couple of reasons,” said Jennifer Kanady, PhD, lead clinical innovator for Sleep Big Health (the maker of Sleepio program). “First, this study demonstrated that digital CBT not only improves nighttime symptoms of insomnia but also improves daytime functioning as well … and, second, the benefits of digital CBT on daytime functioning were maintained four months after discontinuing treatment.” Additionally, she said that the positive results appear to hold up well in more general samples of patients, as many of the people in the study had mental or physical health comorbid conditions.

A 2017 review of dCBT for insomnia provides a comprehensive examination of the technology, including provider-guided dCBT and fully automated dCBT, along with a discussion that answers commonly asked questions about subjects such as its cost-effectiveness and the demographic and clinical predictors of improvement with dCBT (Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2017;3:48-56).

One caveat when using dCBT with patients who have sleep apnea, Dr. Kanady underscored, is the need to address the sleep apnea to improve efficacy of CBT for insomnia. “While digital CBT for insomnia is likely effective for those with both insomnia and sleep apnea, those with untreated sleep apnea will still experience daytime symptoms, such as excessive daytime sleepiness, and would benefit more from digital CBT once the sleep apnea has been properly addressed,” said Dr. Kanady.