INTRODUCTION

Bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP) is an uncommon congenital anomaly resulting from disruption of the nerve supply to the muscles of the larynx that typically presents at birth with upper airway symptoms such as stridor, chronic respiratory insufficiency, dysphagia, and respiratory distress. The etiology of this condition varies; while most cases are idiopathic, BVFP can also be the result of injury related to cardiac procedures, neurogenic disease, birth trauma, or other causes (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41:889-901). Congenital BVFP reportedly accounts for 30% to 62% of cases of pediatric vocal cord paralysis, and can be associated with substantial upper airway obstruction requiring urgent surgical intervention in 50% of patients (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:349-355).

Explore This Issue

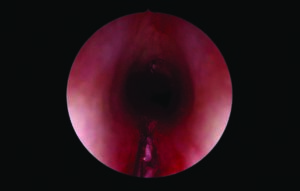

November 2021Historically, congenital BVFP was managed with tracheostomy to secure a stable airway and subsequent expectant management in anticipation of spontaneous resolution of the condition. Though previous studies of children with BVFP have shown that the majority of patients undergo tracheostomy for initial management of this condition, it is important to note that tracheostomy is a procedure associated with high morbidity and mortality, and should be avoided if possible (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110325). More recent studies have identified congenital BVFP management methods that succeed at securing airway patency while avoiding the need for a tracheostomy. These procedures include, but are not limited to, cricothyroid botox injection, vocal cord lateralization, arytenoidectomy, cordotomy, and, more recently, endoscopic anterior–posterior cricoid split (EAPCS) (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:349-355; Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110325) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Zero degree Hopkins rod telescope demonstrating endoscopic anterior and posterior cricoid split. PEREIRA NM, MODI VK. LARYNGOSCOPE. DOI:10.1002/LARY.29752

While the aforementioned procedures have all been described with variable success, EAPCS has emerged as an alternative that is nondestructive and can offer a long-lasting solution to congenital BVFP while avoiding tracheostomy and minimizing the risks associated with other procedures (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110325; Laryngoscope. 2018;128:257-263). In 2017, Rutter and colleagues published a review of 19 patients who underwent EAPCS for congenital BVFP, 84% of whom were able to avoid the need for tracheostomy (Laryngoscope. 2018;128:257-263). Subsequently, Windsor and Jacobs described a series of six patients who underwent EAPCS with balloon dilation for congenital BVFP, 50% of whom were able to avoid the need for tracheostomy entirely, suggesting that EAPCS is effective in improving airway symptoms in a number of patients with this condition (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110325).

The case presented here demonstrates this approach for management of BVFP in a five-week-old patient who presented with stridor, upper airway obstruction, and dysphagia. This article is unique in that it presents a step-by-step surgical video of EAPCS (see supporting video).

METHOD

Preoperative management of patients with congenital BVFP includes a full history and physical examination including fiberoptic flexible laryngoscopy. A magnetic resonance imaging is also recommended to rule out intracranial pathology (i.e., Arnold–Chiari malformation).

While under spontaneous ventilation, the patient is placed in suspension with a Parsons laryngoscope of appropriate size. A false vocal fold retractor is then placed in an inverted fashion and suspended to the Mayo stand.

Next, a sickle knife and straight microlaryngeal scissor are used to divide the posterior cricoid completely. The full posterior cricoid division is ensured using a straight suction and a curved alligator. Note that the interarytenoid muscles remain intact and are not divided. Bleeding throughout the procedure is controlled with the use of oxymetazoline-soaked pledgets.

The anterior portion of the cricoid ring is then divided with a sickle knife, taking special care to not divide the anterior commissure. A hand may be used externally for palpation. Again, a curved alligator can be used to visualize the extent of cricoid division. An upcurved microlaryngeal scissor is then used to divide the remainder of the anterior cricoid.

Next, balloon dilation is performed using a size larger than the sized airway. The balloon is inflated for approximately 30 seconds to 2 minutes, depending on the patient’s level of saturation, and then removed. The area is then inspected to ensure that the anterior and posterior cricoid have been fully divided.

At the conclusion of the procedure, the patient is nasotracheally intubated with a half-size larger endotracheal tube (ETT). A direct laryngoscopy is performed two weeks postoperatively to evaluate the airway. At this time, the cricoid edges should be healing in a distracted position. This patient is then intubated with a half-size smaller ETT and given 24 hours of perioperative steroids. The patient is extubated the following day.

Subsequent balloon dilations are performed as needed if there is progressive stridor or upper airway obstruction.

RESULTS

The video demonstrates the use of EAPCS for management of congenital BVFP. Postoperative management involves nasotracheal intubation with subsequent evaluation of the airway to assess healing at the surgical site.