A Although U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is ubiquitous in the healthcare industry and medical community, knowing how the organization works to approve medical drugs and devices may be part mystery, part bewilderment, and for some, part aggravation given the bureaucracy typical of any large organization.

Explore This Issue

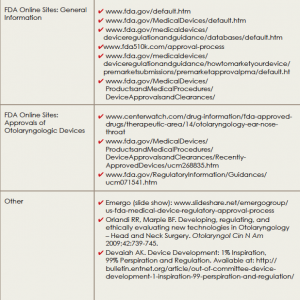

May 2015Tomes have been written on the FDA approval process, and easy-to-follow online resources are available to help those interested in navigating this process (See “Resources on the FDA Approval Process,”). This article is not meant to replace these resources, but will instead provide a brief primer on the FDA approval process with a focus on medical devices.

“Otolaryngology is a tech-heavy specialty … and we are driven to be very creative through technique and technology,” said Anand K. Devaiah, MD, associate professor in the departments of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, neurological surgery, and ophthalmology at Boston University School of Medicine.

Dr. Devaiah believes it is important for otolaryngologists to have a working knowledge of the process a device goes through as it moves from the idea phase through implementation and, in between, how it must move through the FDA approval process. To this end, as chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) Medical Devices and Drugs Committee, he and his committee members have worked through different channels to help otolaryngologists understand and utilize this process.

FDA Approval Process: Medical Devices

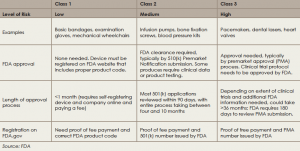

Medical devices in the United States are regulated by the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). The first step in obtaining FDA approval for a medical device is to determine which of the three classes the device falls into, based on risk potential and complexity. Devices in all three classes must be registered on the FDA website, but only devices in classes 2 and 3 are required to undergo an approval process (see “Approval Process for Devices, by Class,” below).

There are two pathways for approval for class 2 and class 3 devices. For class 2 devices, a pathway known as the 510(k) is used if the proposed device can be shown to be substantially equivalent to one that has already received FDA approval. Typically, this pathway does not require clinical evidence of efficacy.

According to Richard R. Orlandi, MD, professor in the division of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City, otolaryngologists must understand that FDA approval does not provide evidence of efficacy for most medical devices. “The FDA deals with safety, but the approval process does not usually address efficacy,” he said. “In an ideal world, we would have efficacy proven when a device hits the market, and there would be solid high level evidence. But, by and large, because of the financial realties of bringing the device to market, that is usually not the case.”

For class 3 devices, which comprise approximately less than 10% of devices, clinical efficacy is required. To gain approval in this class, devices follow a pathway for premarket approval (PMA) that requires evidence of clinical efficacy and safety before approval.

Once most devices are registered on the FDA website, manufacturers are required to comply with the FDA Quality System Regulation (also known as Good Manufacturing Practice or GMP). The FDA conducts random inspections for compliance, which can occur at any time after the device is registered online and includes inspection of suppliers.

Adoption of a Newly Approved Medical Device

Given the lack of efficacy data on most newly approved medical devices, one main challenge for otolaryngologists is how to determine when and if to use a new device.

Physicians are ethically bound to do what is best for the patient, said Dr. Orlandi, so the desire to help the patient using a new technology has to be balanced with the knowledge that the evidence on efficacy (and cost) are not fully known. “That is the challenge, and therein lies the difficulty for physicians to decide when to employ a new particular device in a particular clinical setting,” he said.

The advice he gives physicians is to find out as much as possible about the science behind a new technology and to see if the basic principles behind the purported benefits of the technology make sense. Often, he said, the only evidence available is provided by the company developing the device, and physicians should take that with a “grain of salt.” Dr. Orlandi also emphasized the need for clinicians who help develop and promote new technologies to be upfront and disclose any potential conflicts of interests, to help physicians assess and interpret the evidence.

Because cost is a major factor affecting the feasibility of implementing a new technology in the clinical setting, Dr. Orlandi emphasized the need to look at this factor within the context of the entire value of a technology to a patient. “Sometimes we get wound up about cost, but cost is only one part of the equation,” he said. “It is the change in the outcome of the patient over cost that really determines what the value is for the patient.”

When considering cost, Dr. Orlandi said the acid test is if the new technology would be worth paying for if it was for your own family member. For example, there was initial concern about the cost/effectiveness ratio for balloon dilation technology in sinus surgery. According to Dr. Orlandi, adoption of this new technology is resolved, now that evidence showing efficacy is available and CPT codes have been established.

Another example, he said, lies with image guidance for sinus surgery. While once a new technology generating controversy, is now an established practice.

Dr. Devaiah highlighted the importance of a post-market analysis for establishing the benefit and safety, or lack thereof, in a new technology. To address the cost issue, he said, early adopters often have to work with their institutions, practices, and sponsoring companies to mitigate the cost in order to use the technology. He also emphasized the need to tell patients if a device is being used off label or is investigational.

Most medical devices that require FDA approval are class 2 devices deemed to have potentially moderate risk and complexity and are approved through the 510(k) pathway to establish equivalency to a previously FDA approved device. Approval of most of these devices does not establish efficacy; this occurs only after clinical use and post-marketing testing. Otolaryngologists need to be aware of this fact when adopting a new technology in clinical practice, making sure to balance the desire to help a patient by adopting a new technology with a clear understanding of the lack of evidence regarding its efficacy.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.