On these pages in 2010, Linda Brodsky, MD, discussed the gender gap in compensation and leadership positions in otolaryngology (ENTtoday. February 1, 2010. Available here). How far have we come since she highlighted issues of gender inequity nearly a decade ago?

In the two decades since I was a medical student rotating in otolaryngology, women have made progress in leadership roles in our academic societies and training programs. However, progress toward equity in our specialty has not come quickly enough.

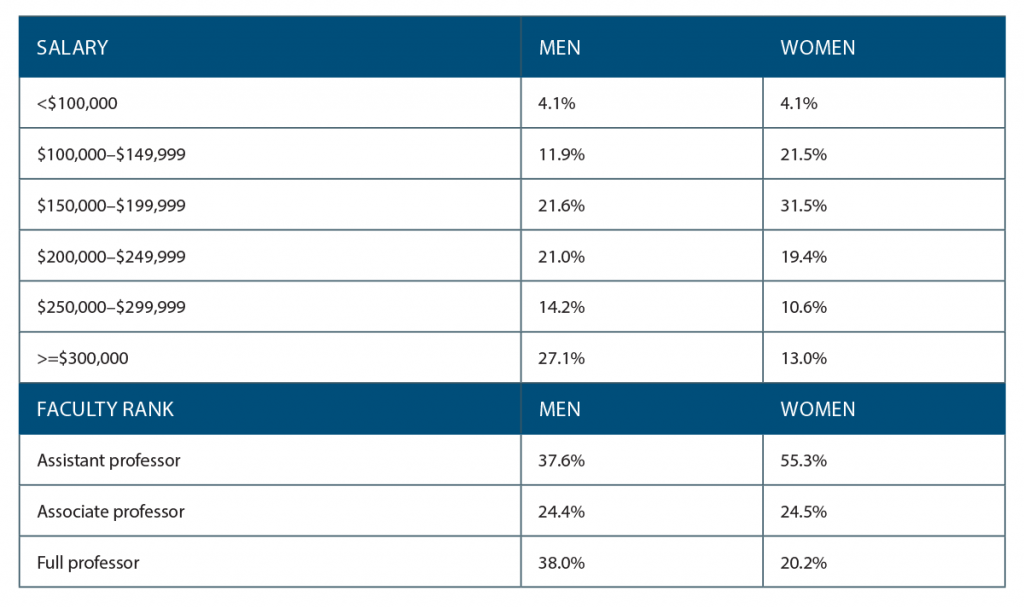

A pay gap still exists in salaries for women in otolaryngology. In 2004, Jennifer Grandis, MD, a professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of California San Francisco, reported a 15% to 20% gender pay gap even after controlling for confounding variables (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:695–702). More recent data suggests this pay disparity persists. The 2018 Medscape survey of full-time otolaryngologists found that women were paid $75,000 (19%) less than men. A 2016 study of 10,000 university physicians also found a pay gap for female physicians despite controlling for experience, faculty rank, specialty, research productivity, and clinical volume, with surgical specialties demonstrating the largest absolute adjusted sex differences in salary (JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294–1304) (See “Sex Differences in Physician Salary and Rank in U.S. Public Medical Schools,” below).

(click for larger image) Table 1. Sex Differences in Physician Salary and Rank in U.S. Public Medical Schools

Source: JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1294–1304

Female otolaryngologists are paid less than male colleagues right out of residency (Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:193–201). Some skeptics may still not believe a pay gap exists, while others may attribute a gap to women’s career choices. However, we have no recent data to determine whether women see fewer patients or perform fewer procedures or decline leadership opportunities, as some may assume, to explain lower salaries for women in our specialty. The other possibility is that women are not being paid equally for equal work and are not provided the same opportunities to earn a salary comparable to their male colleagues.

Research funding in otolaryngology also has a gender gap, with women awarded less money per NIH-funded grant than men at both the assistant professor level and at 10 to 20 years of experience. Women are also awarded fewer R-series grants, with less money awarded per grant (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149:77–83). Women were 31% of recipients of NIH otolaryngology funding from 2005 through 2014. However, 78% of female recipients had a PhD versus 55% of male recipients; only 21 of the 331 recipients were female physicians. (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:774–780). A study in Lancet found the gender gap in research funding could be attributed entirely to the score of the scientist, not the science itself, with lower scores for female applicants (Lancet. 2019;393:531–540).

I left my position as a physician–scientist after my research repeatedly was not funded; this may have been entirely due to my own failings and nothing to do with gender, but I wonder how many women in otolaryngology have left research due to inequities in funding and support.

Active Measures

Women have been told that we can fix gender inequity by trying harder, saying “yes,” negotiating more, and “leaning in.” But even if the pay gap is closing, models predict 20 to 30 years until we reach parity. I don’t want to wait that long for women to have fair compensation for the work we do. Gender equity involves active measures, not passive waiting.

Data on why the pay gap in otolaryngology persists is limited, with little research on this topic since Dr. Grandis’s paper. Objective data on salary is difficult to find, other than for some state universities (which is how I was able to compare my salary to my colleagues’ at my previous job). Last year, Sarah Dermody and colleagues reported equal compensation for female and male otolaryngologists at the Veterans Administration, which does make salary information public. (Laryngoscope. 2019;129:113–118) The use of specific and objective criteria for salary was cited as a key reason for pay equity, but transparency could also play a role. At my own institution, I am on the same salary scale as my colleagues; there are no bonuses for productivity, research, or other metrics. I know I am paid the same as my male colleagues.

Questions about gender equity are for leadership to answer, not problems for women to solve alone. —Erin K. O’Brien, MD

To close the pay gap, first, stop putting the onus on women to fix it. Next, look at your own data; are men and women paid equally in your department or office? Is salary information transparent? Are criteria for salary and promotion public and objective? If there is a pay gap, investigate if there are systemic issues contributing to unequal pay. Are referrals distributed equally? Are men and women billing at the same level for similar visits and procedures? Are women nominated for leadership positions or are they given more of the office “housework” of less meaningful non-clinical tasks? Does your institution provide support for working parents so that women can continue with their career paths and men can help shoulder parental responsibilities equally?

The pay gap will close faster when those in leadership see equal pay as a quality metric. Perhaps gender equity should be included in calculating U.S. News and World Report or Doximity rankings. We could examine the effects of women in otolaryngology like studies in business, where having more women in leadership translates to higher profits, or other medical specialties, where female hospitalists and cardiologists have higher survival rates for inpatients and female MI patients, respectively. We could look at the outcomes for our patients or departmental metrics in relation to gender equity and inclusion. But I would argue that we don’t need data to know that women in otolaryngology should be paid and promoted fairly and equally.

To close the gender gap in research productivity and funding, start by removing the possibility of implicit bias in research grant application and journal article reviews by blinding the reviewers to the name (and gender) of the authors. Chairs should ensure that female residents and faculty members have mentors and sponsors for research. There should be accountability for the chair if women aren’t matching their male colleagues in academic productivity and leadership promotion. Provide transparency for research support among the faculty; who is getting research coordinator support, research time, and internal funding, and what is the dollar amount?

Questions about gender equity are for leadership to answer, not problems for women to solve alone. As Dr. Brodsky wrote, “I am convinced that equality will never be realized as long as the victim is to police the system [and] be the whistleblower.” If leadership makes gender equity a priority, we will get to parity faster. I don’t want another woman in otolaryngology to have to write about the gender gap in salary and research funding for these pages in another decade.

Dr. O’Brien is assistant professor of otolaryngology and chair of the division of rhinology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.