Years of robust research have shown the importance of sleep to human health. Studies spanning several decades document the profound impact of poor quality and insufficient sleep on an array of health issues, including hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration and dementia, and impaired immune functioning.

But sleep wasn’t always considered critical to health; only with an evolving deeper physiological understanding of the science of sleep and circadian rhythms did sleep emerge as a component of health that warranted its own subspecialty. In 2003, sleep medicine was recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and in 2005 the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine was established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, which itself has only been around since 1975.

Climate change too has evolved over time as its effects on ecosystems, including human health, have become ever more apparent. Here too, robust research is increasingly showing the ill effects of environmental changes, from rising temperatures to severe weather events, on human health—so much so that two of the most prominent medical journals have established content devoted to the intersection of climate change and health:

- In 2016, The Lancet launched the “Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress and Climate Change.” Among other resources, the Countdown publishes an annual report describing key areas of health and climate change.

- In 2019, the New England Journal of Medicine launched “Climate Crisis and Health” to provide articles and resources on the effects of climate change on physical and psychological health.

It isn’t surprising, then, that some investigators are now bringing these two robust avenues of research together to examine how climate change affects sleep.

Finding the Connection

© fizkes / shutterstock.com

Nick Obradovich, PhD, senior research scientist and principal investigator at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in the Center for Humans and Machines in Berlin, is one of the first researchers to investigate the connection between sleep and ambient temperature. In 2017, he and his colleagues published the first evidence showing that climate change may disrupt human sleep (Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1601555).

Dr. Obradovich initiated the study of the effects of nighttime temperature on sleep when he noticed that he and his friends were experiencing disrupted sleep during a heat wave in San Diego in October 2015. He realized he had access to a data set by which he could study the social impact of climate change on sleep.

“At the time, I assumed there would be extensive literature on sleep quality and ambient temperatures, but there really wasn’t any,” he said. “I was surprised then and am more surprised now at the lack of attention to this topic because even in the absence of climate change, understanding environmental determinants of sleep quality is a really big deal.”

Daniel I. Rifkin, MD, PhD, founder and medical director of Sleep Medicine Centers of Western New York and a clinical assistant professor of neurology at the State University of New York at Buffalo, credited Dr. Obradovich’s research with igniting his own interest in looking more closely at the effect of climate change on sleep.

“The field of sleep medicine needed a study that compiled all the studies [on climate change and sleep] to help us understand how we study this further,” he said. “We’ve learned a lot about all the effects of climate change such as rising temperatures, more extreme weather events, and their downstream effects like ticks moving further north, waterborne illness, and people displaced from their homes, but we really don’t understand fully just yet how that will affect sleep.”

To gain a better answer, he and his colleagues undertook a systematic literature review of the available data and published their findings in Sleep Medicine Review (Sleep Med Rev. 2018;42:3-9).

The literature review looked at empirical studies published between 1980 and 2017 that examined the association between climate change and any aspect of human sleep. Of the 1,719 studies identified, only 16 studies met inclusion criteria. Studies excluded from analysis included non-human studies, laboratory or experimental physiological studies, articles on wind turbines, review articles, and commentaries or letters. The final 16 included studies that examined temperature and sleep (6), extreme weather events and sleep (7), and floods, wildfires, and sleep (3).

According to Dr. Rifkin, enough evidence from these studies clearly showed that climate change affects total sleep times and can lead to insomnia. “This was shown over and over in our study and was more prominent in vulnerable populations like the elderly and the socioeconomically disadvantaged,” he said.

Highlighted in the study were the specific effects of temperature and weather events on total sleep time, which diminished due to sleep disruption, rather than self-induced insufficient sleep or new-onset sleep disorders. Difficulty with sleep maintenance was also widely seen, in contrast to difficulty with sleep onset.

A big takeaway from the review, however, is that there are significant gaps in the literature regarding links between sleep and climate change due to particular types of events (e.g., drought); differential effects on sleep when power is lost during extreme heat events, for example; and the effect of climate change on sleep health services.

“The studies themselves weren’t that robust,” said Dr. Rifkin, citing Dr. Obradovich’s study as the outlier and one of the most robust studies to date.

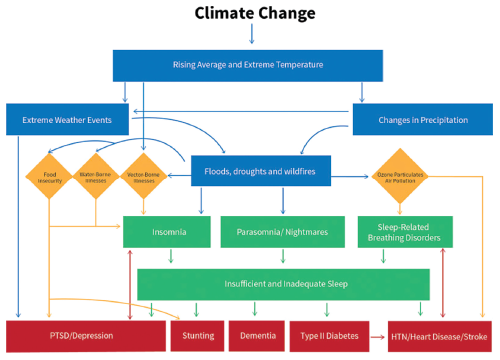

To help broaden and deepen an understanding of the effects of climate change on sleep, Dr. Rifkin and his colleagues developed a conceptual framework for guiding future research based on identifying emerging climate change threats and their effects on sleep (see below). Based on some of the findings of their literature review, the schematic highlights the need for more research to establish a clear association between the effects of climate change and sleep.

Ambient Temperature and Sleep

Dr. Obradovich’s 2017 study, which the authors call an “inaugural” investigation into the relationship among climatic anomalies, insufficient sleep, and projected climate change, also used data from 765,000 respondents to a question on the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey that asked on how many of the previous 30 days they had felt they did not get enough rest or sleep (Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1601555). Responses to the question were gathered between 2002 and 2011.

Each respondent’s answer was documented by interview data and geolocated to the city level, and then coupled with nighttime temperature data taken from the National Centers for Environmental Information Global Historical Climatology Network Daily, which provides station-level daily temperature and precipitation information, as well as climate normals data. The study found a robust link between insufficient sleep and atypical nighttime temperatures. “As normal nighttime temperatures increased, so too did reports of poor quality or worse sleep,” said Dr. Obradovich.

When looking at subgroups of respondents, Dr. Obradovich and his colleagues also found that the largest impact of atypical nighttime temperatures occurred during the summer and among vulnerable populations, including the elderly and people in low-income groups. “The group of low-income elderly had the highest effect size by a substantial margin in terms of the relationship between nighttime temperature and poor-quality sleep,” Dr. Obradovich added.

As normal nighttime temperatures increased, so too did reports of poor quality or worse sleep. —Nick Obradovich, PhD

One clear limitation of the study, acknowledged Dr. Obradovich, is its reliance on self-reported sleep quality. To overcome that issue, he and his colleagues published another study in 2020 in which they compiled more objective sleep measurement data from wearable devices that record nighttime sleep to assess the impact of ambient heat. Between 2015 and 2017, sleep measurements drawn from 7 million nighttime sleep records compiled from these devices worn by people in 68 countries were linked to local daily meteorological data.

Currently published online prior to publication, this study, led by Kelton Minor, PD, Copenhagen Center for Social Data Science, University of Copenhagen, found that rising nighttime temperatures were associated with shortened sleep duration mainly by delaying the onset of sleep. Residents of lower-income countries, older adults, and females were substantially more affected by sleep loss due to temperature.

Using climate model projections in both studies, Dr. Minor and colleagues assessed the potential impacts of future climate changes on human sleep and found it likely that climate change will continue to increase the frequency of warmer nighttime temperature, which, in turn, will further erode human sleep.

The public health risks of populations of people experiencing insufficient sleep are potentially enormous, Dr. Minor and his colleagues suggest, citing data linking insufficient sleep to an increased risk of negative behavioral, social, and economic outcomes. Noting the potential for sleep to mitigate these negative outcomes, they state in their article that “addressing the nocturnal impact of rising ambient temperatures on human sleep may be an efficient early intervention to reduce downstream adverse behavioral impacts linked to insufficient sleep.”

Natural Disasters and Sleep

Evidence of the negative downstream psychological consequences of disturbed sleep caused by climate change is highlighted in a 2020 study by Betty S. Lai, PhD, the Buehler Sesquicentennial Assistant Professor of Counseling, Development & Educational Psychology in the Carolyn A. and Peter S. Lynch School of Education and Human Development at Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Mass., and colleagues. They conducted a bi-directional assessment of sleep problems and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in 269 children after they were exposed to Hurricane Ike in Texas in 2008. Assessments were taken at eight months and 15 months post-hurricane (J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45:1016-1026).

The study was undertaken to fill a gap in the literature on the effect of natural disasters on sleep in children. “This is a problem because our work and that of others is showing that children may have trouble with sleep after disasters,” said Dr. Lai, who’s the senior author of the study. “Sleep is important in helping children cope with stress.”

I would argue that our role as physicians is to speak about public health issues and be a voice behind public health policy to raise awareness with our legislators. —Neelima Tummala, MD

Overall, the study found that a “sizable minority” of children reported sleep problems at eight months following Hurricane Ike that persisted up to 15 months after the hurricane. Younger-age children and those with higher levels of sleep problems at eight months were at higher risk of having sleep problems at 15 months.

In the study’s main assessment, the investigators found that while PTSS did predict sleep problems, sleep problems did not predict later PTSS. “Post-traumatic stress symptoms seem to contribute to and worsen sleep problems for children,” said Dr. Lai.

Why This Matters to Clinicians

“All healthcare providers need to recognize that climate change will have the greatest healthcare impact, even greater than the COVID-19 pandemic, in the coming decades,” said Dr. Rifkin. “It’s something we all need to start to recognize and realize what we as clinicians can to do help address it, regardless of the area of practice.”

Neelima Tummala, MD, an otolaryngologist and clinical assistant professor of surgery at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, D.C., has a special interest in the effects of climate change on population health. She emphasized that otolaryngologists play a key role in speaking out about public health issues like the effects of climate change on health, both as educators of their patients in the clinic and as spokespersons to help affect policy.

“I would argue that our role as physicians is to speak about public health issues and be a voice behind public health policy to raise awareness with our legislators,” she said. “It starts in the clinic with recognizing that there’s a real risk factor [of the effect of climate change on health] and that we need to do something about it.”

Beyond the larger advocacy role, clinicians also play a role in addressing health issues such as sleep problems related to climate change in their daily clinical practice. Dr. Rifkin urges clinicians to focus more on sleep in terms of health prevention, similar to a focus on exercise and diet. “We spend a third of our lives sleeping, but we focus our health prevention on waking hours,” he said.

To shift the focus to include sleep, Dr. Rifkin and his colleagues have developed a “Restcue Kit” in their clinic for patients who need help with sleep disorders. The kit includes a sleep mask, earphones, a small pen and notebook to record thoughts prior to bedtime, and a lavender-scented stick.

Dr. Tummala also noted that clinicians play a critical role in educating patients about how climate change can affect their health by, for example, providing advice on how to keep their core body temperature cooler when exposed to higher ambient temperature. “This is particularly important for children, who are less able to regulate their own body temperature as compared to adults,” she said.

Dr. Lai also underscored the importance of talking to children who have been exposed to natural disasters to ask how they are doing. “Asking a child whether they are experiencing problems doesn’t make the problem worse,” she said. “Most children report relief that an adult gave them an opportunity to talk about what they’re experiencing.” Dr. Lai noted, however, that before asking children questions, clinicians should be sure to have referrals ready so the child and family can receive help.

Dr. Rifkin highlighted the need for more attention and research on sleep in humanitarian settings. Dr. Rifkin and his colleagues plan to study how their “Restcue Kits” impact sleep in displaced persons, particularly given the high rates of displacement caused by the COVID-19 pandemic that have led to increased homelessness. “People displaced from their homes have a hard time sleeping outside of their normal home environment,” he said. “If they were just given simple things like a sleep kit, it might help.”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

How Climate Change Disrupts Sleep

Conceptual Framework on the Consequences of Climate Change on Human Health via Sleep Disruption (published in Sleep Med Rev. 2018;42:7; used with permission from Daniel I. Rifkin, MD).