Clinical Scenario

You are seeing a long-time patient of yours, a 52-year-old male, who has experienced fluctuating vocal weakness for several years. He is a medical device salesman with ample opportunity for vocal usage. In your past examinations, you have noted some subtle weakness of glottic closure with soft vocalization, but no other worrisome findings. The patient has also related over the years that his jogging pace has slowed down, which he had felt was commensurate with his overall physical aging. Today’s examination reveals no new information or findings, but you note that the patient appears to be concerned about something, appearing more serious than usual, and you inquire about what is bothering him.

The patient explains that he has recently become concerned—after researching his symptoms online—that he may have early Parkinson’s disease, given the vocal weakness and his jogging sluggishness. He has become convinced that he is experiencing the early onset of this disease, and without consulting his primary care physician or you, he has ordered, and submitted, a home genetic testing kit to determine whether he has a genetic marker for Parkinson’s disease.

He is now “worried sick” about the forthcoming results and wants you to explain to him how this genetic testing works. Clinically and historically (no history in his family), you believe Parkinson’s disease is a consideration, albeit low, at this time. You really have not taken the time to learn much about the risks and benefits of “direct-to-consumer genetic testing,” so you feel ill prepared to counsel him. You are especially concerned about the ethical implications of individuals receiving this information without any context that might help them to understand the results. How should you respond to the patient?

How would you handle this case?

Discussion

© Henrik Dolle / shutterStock.com

Genetic testing for the determinants of cleft lip and palate risk for parents with the disorder, or with one affected child, has been a vital component of craniofacial anomalies family counseling. Following the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, the consumer’s capability to acquire vast information on personal genetic data has burgeoned. While the identification of medically important genetic information has opened the door to the salutary promise of personalized medical care and furthered the exploration of genetically linked diseases and disorders, ethical and moral concerns accompany this progress. As with technological advances such as in vitro fertilization, questions of an ethical nature must be addressed.

In the past decade, direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC-GT) has resulted in regulatory, scientific, and ethical scrutiny owing to the fact that it bypasses the traditional medical care model of shared decision-making between patient and physician. Not dissimilar to independent laboratory testing for a range of sexually transmitted diseases, for which the information is given to an individual by phone call or on a data sheet without physician counseling regarding interpretation, DTC-GT provides only genetic “risk” information, with no correlation of this “risk” within the total context of the patient’s health status. There is no inherent interpretation of the implications of this information for the individual, especially considering the wide variation in the clinical penetration of certain disorders, as well as the myriad facilitating and suppressive influences of the individual’s health and life on genetically associated disorders.

The testing process is simple: The individual contracts with a company, pays a fee, and then receives a kit that includes a receptacle to fill with the individual’s saliva. Some time after the kit is returned by mail to the company, the individual is given access to the selected information via a secure site with password protection. The processes involved have come under scrutiny in the past by both the scientific community and the federal government. In April 2017, after an extensive regulatory oversight process, the U.S. FDA allowed marketing by 23andMe for its personal genome service, which tests for 10 health conditions of significance. These 10 disorders include Parkinson’s disease and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The National Institutes of Health has published a very helpful primer and home reference for patients and physicians on DTC-GT that is recommended reading for all physicians, including otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeons (“Genetics Home Reference.” Published July 20, 2017.).

This extensive informed consent process—a necessary component of autonomy, which is a cornerstone of medical ethics—is incomplete in direct-to-consumer genetic testing.

Privacy and Protection

A major concern for both physicians and medical ethicists with regard to DTC-GT is the lack of a fully informed consent process. As surgeons, we routinely use this process, both for the protection of the patient and our own professional protection, but also as an ethical responsibility to provide the patient with as much information as possible to make the best decision for their personal health. The patient is encouraged to ask questions to better understand the risks and benefits, and the surgeon

fully answers the questions. This extensive informed consent process—a necessary component of autonomy, which is a cornerstone of medical ethics—is quite incomplete in the mass marketing process of DTC-GT. Patients who order these tests without consultation or advice from a physician may misinterpret the results, or at least may not understand their meaning within the broader context of their own health environment, and thus may make ill-advised decisions.

All clinicians must be familiar with the details of DTC-GT, because patients, as well as friends and family members, may make inquiries of us regarding our opinions on this enterprise. The testing company 23andMe presents information on the issues of privacy and data protection for the purchaser that is important for physicians to review, including content on meaningful choice, privacy by design, third-party sharing, data security, and research. Some individuals may not understand the implications of the data handling and should be given some explanations, preferably by their physician, of what could “go wrong.” While there are conspiracy theories on how this data may be obtained and utilized by insurance companies and/or employers, the more likely scenario is that “data hacking” could result in the exposure of an individual’s personal genetic information, and no one knows just where that might lead.

Interpretation and Analysis

Physicians should consider some significant medical ethical issues for their patients, including informed consent, decision-making by the individual based on test results without knowledgeable physician interpretation, appropriate risk/benefit analysis of data acquisition, limitations of testing (including false positives and false negatives), and failure to interpret data appropriately in the context of the individual’s past and current health/wellness status. Individuals may place an order for genetic-based health testing without fully understanding the serious personal and family implications of the information they might receive.

Some individuals may be able to comprehend the impact of receiving genetic risk data regarding, say, Parkinson’s disease, on their own health, but may not fully appreciate the potential implications of sharing that information with other family members, especially young adults, for whom the data may cause considerable angst. Additionally, even for physicians, it is usually not possible to give a reasonable prediction of when—or if—a patient might begin to experience clinical symptoms of a disorder such as Parkinson’s disease. The patient’s diet and nutritional status, level of exercise, mental stimulation and agility, medication list, immune status, outlook on life, environmental exposures, and so many other factors play a role in modulating even genetically associated diseases. All of this can be discussed with the individual in a consultation with her/his physician but is not available without such professional input.

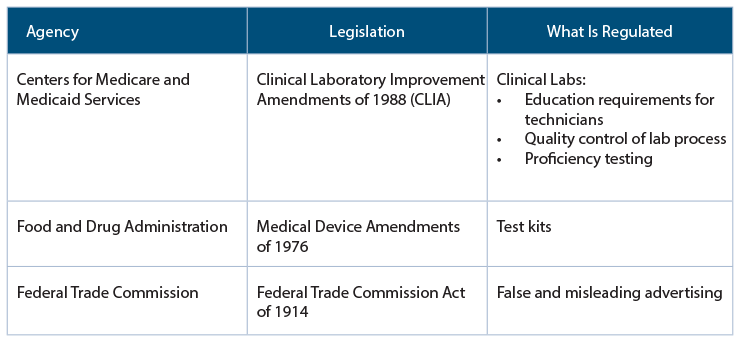

Federal Regulation of Genetic Tests

Security

Finally, the individual must be apprised of potential risks to the integrity of that very special personal health information should there be a breach of access security to the genetic database. The individual needs to consider how the data are protected, who has access to them, how they might be used in a research context, and whether or not employers and/or insurance companies could receive the data. These are all very serious concerns. Yet, it must be emphasized that the utilization of genetic information, on the whole, is still a very positive development with respect to personalized medicine and molecular drug therapy, helping us to better understand genetically associated diseases and how other health factors may influence their clinical course, and clarifying ethical and moral issues inherent to human genetics.

In the case of the patient in this scenario, at least now you will have the opportunity to become informed about DTC-GT and to have a meaningful discussion with him before he receives his genetic test results. You will be willing to review the data—even just the risk identification for Parkinson’s disease, if he so chooses—and counsel him if there is a high risk for the disease. Indeed, you may well have been planning to request a neurological consultation, because Parkinson’s disease was one of your differential diagnoses based on his laryngeal and musculoskeletal symptoms, even before he offered the information about the genetic tests. Support him, inform him, and work with him on a diagnosis and treatment plan as appropriate. Above all, be his physician.

Dr. Holt is professor emeritus in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

Key Points

- While the identification of genetic information has opened the door to personalized medical care, ethical and moral concerns accompany this progress.

- At-home genetic testing doesn’t offer a fully informed consent process, and individuals may not understand the serious personal and family implications of the information.

- There is no inherent interpretation of the implications of such information for the individual.