Rather than being a single disease, head and neck cancer has been described as a collection of rare diseases, said Baran D. Sumer, MD, professor and chief of the division of head and neck oncology in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and leader of the head and neck cancer disease oriented team at the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center in Dallas. “This means that pathologic expertise in accurate diagnosis is essential,” he said. “The various types of cancers that can exist in the upper aerodigestive tract, skin, and salivary glands, as well as other types of tissues in this complex region, make diagnosis and management challenging.”

Indeed, because of these challenges, patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer may encounter discrepancies in the pathology of their condition depending on the type of care center where they are diagnosed—a phenomenon documented by a retrospective chart review of 159 adult patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer presenting to a tertiary care center between 2008 and 2014. Of the 159 patients who had documentation of tumor stage that was assigned by a community-based practice, 53% had a tumor staging change made at the tertiary care center, with 43% of these patients upstaged and 10% of patients downstaged; fifty-one percent received a different treatment than had previously been offered at the community practice (Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3:290-295).

The researchers noted that the differences in tumor staging may be attributed to overall volume and experience with head and neck cancer, as well as the availability of additional specialists, said Carol R. Bradford, MD, MS, one of the paper’s authors, who is the dean of the College of Medicine and vice president for health sciences at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. “For example,” she said, “the diagnosis of salivary gland malignancies and other rare head and neck malignancies is extraordinarily challenging.”

Certainly, there are differences between how a community-based practice and a tertiary care center might approach head and neck cancer diagnosis. But what are they, why do they exist, and what options are there for collaboration?

Differences in Diagnosis and Pathology

For diagnosis of most common otolaryngologic conditions, there’s little difference between a small community hospital and a large academic center. “For more rare diseases such as cancer, however, where complex, coordinated care is required and multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment are essential, diagnosis and management can be challenging if a hospital does not have the full complement of necessary expertise,” said Dr. Sumer.

The main difference between smaller practices and larger centers that affects the approach to cancer diagnosis is volume. “A general otolaryngologist must have broad experience in many different diseases, but may see only one or two cancer cases per year,” said William B. Armstrong, MD, professor and department chair of clinical otolaryngology at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in head and neck oncology. “As a head and neck specialist, I deal primarily with head and neck and thyroid cancers, but I don’t manage patients with vertigo or patients with ear or sinus diseases.

“I think general practitioners face challenges in terms of assessing the extent of head and neck cancer on clinical examination, or with imaging that may not be quite as specific or high quality,” he continued. “And with pathology, they generally don’t have the luxury of having a subspecialty pathologist who can look for certain nuances, which is more important for unusual pathologies. This has absolutely nothing to do with the competence of community-based doctors, however, many of whom are very skilled and talented, but more with depth of experience.”

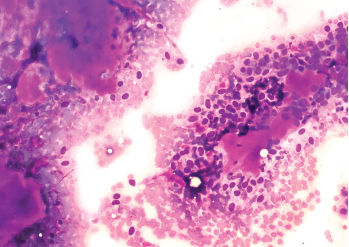

A fine needle aspiration cytology of a benign mixed tumor of the salivary gland (pleomorphic adenoma).

© David A Litman / shutterstock.com

A 2013 study examined the effect on cancer staging and patient management of outside head and neck imaging studies undergoing a formal second opinion reporting by a fellowship-trained academic neuroradiologist with expertise in head and neck imaging. The researchers found that, following the second opinion review, the cancer stage changed in 56% (53/94) of cases and that the recommended management plan changed for 38% (36/94) of patients with head and neck cancer. When compared to the pathologic staging gold standard, the second opinion was correct 93% (28/30) of the time (J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;42:39).

Multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment of patients with head and neck cancers is something that larger tertiary centers are better able to offer, said Andrés M. Bur, MD, an associate professor and director of robotics and minimally invasive head and neck surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine (KU) in Kansas City. At academic centers like KU, this approach might involve input from radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, oral surgeons, pathologists, speech pathologists, and other different medical specialists who all have expertise in head and neck cancer treatment at multidisciplinary tumor board meetings. “We regularly meet to put our heads together and determine the most appropriate staging and treatment recommendations for individual patients,” he said. “All of these specialists have different areas of expertise and a different perspective specifically on the treatment of head and neck cancer. Patients themselves will see a surgeon, a head and neck surgeon, a radiation oncologist, and a medical oncologist. And that level of expertise just isn’t available at most community practices.”

Dr. Bur admitted, however, that having this diversity in experience can present a challenge in scheduling, particularly for patients who may need to travel long distances to reach an academic center. “One issue, particularly in a in a center like ours, is trying to help coordinate schedules so that these patients are able to get the most out of their visit. We have dedicated head and neck cancer nurse navigators who schedule and coordinate visits.”

The variety of diagnostic tests available at more specialized facilities is also an advantage. “I might be able to get additional studies and come up with a more refined diagnosis,” said Dr. Armstrong. “I also might get a little more information on histology, or have better imaging that will allow me to upstage something that may have been downstage; sometimes it goes the other way, or it might be a false-positive test.”

There are opportunities for collaboration between community-based practices and larger medical centers through referrals. “I get a lot of referrals from general otolaryngologists, or sometimes general surgeons, and occasionally dentists and primary care physicians,” Dr. Armstrong said. “Occasionally, a patient might have a neck mass that hadn’t been diagnosed that turned out to be cancer; other times a patient might have a biopsy that shows cancer, and then the referring physician will send a muscle workup.”

Factors in Differing Diagnoses, Staging, and Treatments

Several additional factors beyond patient volume, technical expertise, and multidisciplinary tumor board and team management contribute to discrepancies in diagnosing, staging, and treating otolaryngologic conditions among center types:

Region. The number of available tertiary centers versus community practices varies widely by region. Areas that have a dense population will have far more options, while more rural or disadvantaged areas will have fewer centers that specialize in head and neck oncology. “In this part of the country (eastern Kansas), just due to the sheer distances between many of our patients and the major academic center here, there are a fair number of general otolaryngologists and other practitioners who haven’t necessarily done additional training in head and neck oncology, but who do treat head neck cancers,” said Dr. Bur.

If a clinician isn’t immersed in this world, it can be very easy to become out of date. It’s critical to keep up with the literature to offer patients the most appropriate treatment. —Andrés M. Bur, MD

Scope of Practice. Another difference comes from the time and resources required for general otolaryngologists to keep up to date on the most recent developments in head and neck cancer pathology. “At an academic tertiary care medical center, you have practitioners who really devote themselves to the care of head and neck cancer, an area that’s rapidly changing,” Dr. Bur said. “If a clinician isn’t immersed in this world, it can be very easy to become out of date. Just a few years ago, there was a major change in the way that certain head and neck cancers—specifically oropharynx cancers—are staged. It’s critical to keep up with the literature to counsel patients correctly and to offer patients the most appropriate treatment.”

Technology/Clinical Trial Availability. Availability of a variety of diagnostic tools is probably the greatest barrier to uniform treatment, and this can make a real difference. In one retrospective analysis of the role of positron emission tomography and computed tomography fusion in the management of early-stage and advanced-stage primary head and neck squamous cell cancer, with a blinded evaluation of clinical data and formation of a treatment plan (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:12-16), researchers found that the technology provided additional information that confirmed the treatment plan in 25 out of 36 patients (69%) and altered the treatment plan in 11 patients (31%).

“Some centers may rely on older imaging technology, particularly in more rural and remote areas,” noted Dr. Bur. “They may have out-of-date MRI or CT technology, which we rely on pretty heavily.” In addition, alternative methods of treatment, such as transoral robotic surgery, may not be available in some areas. “Robotic expertise isn’t always available, and therefore patients may not be counseled regarding this particular option at centers that aren’t able to offer this type of surgery,” Dr. Bur added.

Academic centers also often have greater access to a variety of protocols, specifically through clinical trials. One randomized phase II/III trial led by Dr. Bur at his institution that’s currently in the recruitment phase (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04333537) is set to compare sentinel lymph node biopsy surgery and elective neck dissection as part of the treatment for patients with early-stage oral cavity cancer.

The Value of Telemedicine

The use of telemedicine certainly has grown during the COVID-19 pandemic—a recent American Medical Association Physician Practice Benchmark Survey noted that the number of physicians who used telehealth to diagnose or treat patients increased from 15.6% in 2018 to 58% in 2020. “Telemedicine has been available at larger hospitals for several years, but COVID-19 sped up its use just as it sped up the adoption of technologies like online virtual meetings,” said Dr. Sumer. “It has greatly expanded the reach of physicians who are based in large population centers.”

Although the potential is there, many head and neck oncologists prefer face-to-face meetings with patients when possible for diagnosis. “It has been very useful as an adjunct to routine face-to-face care; however, it’s no substitute for the direct physical examination and evaluation of the patient,” Dr. Sumer said. “Therefore, telemedicine should always be supplemented with in-person visits and examinations. Often, however, patients can have easier follow-up appointments through telehealth visits, which is a positive aspect of this technology.”

“The growth in technology during the pandemic has really been one of the positives here in terms of caring for patients in a remote setting,” added Dr. Bur. “However, telemedicine has had a relatively small impact on clinical care for head and neck cancer patients. A big part of that is that we’re so reliant on physical exams—we really need to be able to feel the patient’s neck and look in their mouth, things that we unfortunately can’t do well with telemedicine. Thankfully, as vaccination rates have risen, we’ve been able to get more patients into our clinics in person.”

In addition, some academic medical centers have used telemedicine to create a sort of virtual consultation program, where community clinicians can confer with specialists to discuss their findings and possible treatment plans, but this can be difficult for head and neck cancer. Dr. Armstrong rarely consults with head and neck cancer patients for initial diagnosis using telemedicine. “For certain specialties, like dermatology and psychiatry, and for follow-up medical oncology, telemedicine works really well, and there are some otolaryngology functions that you can do with telemedicine—for example, there are new tools to perform hearing screenings,” he said. “But for much of what we do with the head and neck, this isn’t possible—we use our fingers to palpate and we’ve developed instruments to look where other people can’t see: the scope to look at the nasal pharynx behind the nose, a mirror or the scope to examine the voice box. I am starting to see more patients using their smart phones to send pictures when they have a question on follow-up, however, and that seems to work well. For example, if a patient has some swelling after surgery, we can look at it and say, ‘You know, that’s just postoperative swelling. You’re okay,’ or, rarely, ‘I don’t like that. Come on in.’”

Telemedicine has been very useful as an adjunct to routine face-to-face care; however, it’s no substitute for the direct physical examination and evaluation of the patient. —Baran D. Sumer, MD

Another benefit of using telemedicine for head and neck cancer diagnosis is its availability for patients who may live far from a treatment center. “I have done telemedicine visits to provide a patient with a second opinion. My ability to appropriately stage a patient or provide a treatment recommendation that way is very limited,” said Dr. Bur. “But I’ve also had conversations with clinicians whose patients can’t drive for six hours or afford a hotel stay to get evaluated and receive treatment here. I’ve had many conversations with some of those referring clinicians who send me their cancer patients, consulting with them on specific cases, especially in situations where the patient just can’t get here. Telehealth can also be helpful for some patients to limit the number of times that they need to travel for follow-up.”

Sometimes, distance is only part of the issue. “At the University of Kansas, we’re right on the state line between Kansas and Missouri, but we have a very difficult time seeing patients from the Missouri side who have Medicaid—it’s a major barrier,” Dr. Bur added. “Many of those Medicaid patients don’t have a lot of resources and don’t have the option of traveling to Columbia or St. Louis, Missouri, for their treatment when, in an ideal world, they would just be able to come across the state line and receive their treatment here.”

Dr. Bur has also found telemedicine useful for follow-up appointments for patients who have a low-risk disease that’s easily detectable, such as an early oral cancer or a skin cancer. But, he cautions, there are many head and neck patients, particularly those with a high-risk, advanced disease, who would not be served by a distanced visit, even in follow-up. “It’s so critical to see those patients in person, to be able to look and feel during an examination to make sure that they don’t have signs of recurrence,” he said.

Another advantage of telehealth interaction is the ease of holding meetings between specialists to discuss individual patient pathology and treatment recommendations. “Early in the pandemic, we transitioned to a purely virtual tumor board, held via Zoom,” Dr. Bur said. “Even with universal vaccination of our employees here at the medical center, we’ve remained virtual. One of the things we’ve realized is that the platform really is sufficient for us to have conversations to review the scans. It has definitely changed the way that we communicate as a healthcare team, and it has certainly facilitated communication between clinicians who are at different centers or remote sites. I think it’s very reasonable for a community physician to confer with an academic physician of their same specialty.”

Dr. Armstrong likes to use telemedicine for counseling his patients. “If I take out an enlarged parathyroid and follow up for six months, I’ll look at the scar over telemedicine, review their labs, and talk to them about how they’re doing. Another thing that’s nice is seeing patients in their homes—sometimes you get a clue about their situation by their surroundings. You might be able to help with access to care.”

Renée Bacher is a freelance medical writer based in Louisiana. Amy E. Hamaker is the editor of ENTtoday.

Seeking a Second Opinion

Head and neck cancer is a complicated diagnosis, and some patients may feel more comfortable with a second opinion. Is there a time when it’s appropriate for otolaryngologists to recommend one?

“If it’s a complicated problem with serious consequences, if there are multiple treatment options, or if the treatments are high risk, then it’s probably good to get a second opinion,” said William B. Armstrong, MD, professor and department chair of clinical otolaryngology at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in head and neck oncology. “If a patient asks me whether or not they should get a second opinion, the answer is, “If you feel like you need it, you should have it.’ Other physicians may have a different perspective, and it’s possible that I may miss something.”

Baran D. Sumer, MD, professor and chief of the division of head and neck oncology in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, believes that physicians should always encourage patients to seek a second opinion when it involves a complicated disease like cancer. “I always encourage my patients to seek out care at other centers and seek other opinions, as they may have different approaches that may be more suitable for them,” he said. “I would certainly seek out a second or even third opinion for a loved one if they had a complex diagnosis.”

Andrés M. Bur, MD, an associate professor and director of robotics and minimally invasive head and neck surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine (KU) in Kansas City, believes that it’s appropriate for a clinician to recommend a second opinion any time the clinician doesn’t feel comfortable that he or she is the best person to manage the condition. “The best opportunity to cure a patient of head and neck cancer is always that first shot,” he said. “Once the patient has had a surgery or radiation, if the cancer persists or recurs, it becomes much more difficult to cure.”

The bottom line, said Dr. Armstrong, is that it isn’t about the physician—it’s about what the patient needs to be comfortable. “I tell patients and family members that if someone says you don’t need a second opinion, you probably should run away and go somewhere else.”