An AAO-HNS 2022 workforce survey of 1,790 members showed that 54% of respondents worked in private practice (https://www.entnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2022-Otolaryngology-Workforce.pdf).

An AAO-HNS 2022 workforce survey of 1,790 members showed that 54% of respondents worked in private practice (https://www.entnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2022-Otolaryngology-Workforce.pdf).

Explore This Issue

April 2024A significant amount of medical training, at both the medical school and residency levels, occurs at larger academic hospital systems, however. This can make getting a firsthand view of private practice a challenge for physicians in training.

So, what are residency programs doing to facilitate exposure to and exploration of private practice? Quite a bit, it turns out.

Residents at Boston University Medical Center (UB) in Boston have exposure to attending physicians in private practice through two private practice facial plastic surgeon offices, a rotation at a multi-specialty clinical practice site, and clinical work with a private practitioner who sees patients at the academic medical center once a week, said Michael Platt, MD, MSc, the residency director in the UB department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Additionally, private practice physicians speak about different practice models at a business of medicine lecture series.

“Our program openly supports residents seeking careers in private practice, which allows them to learn and explore different models,” Dr. Platt said. “Residents have direct exposure to mentors in private practice, as well as lectures to help prepare for a career in private practice.”

The Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston offers an elective rotation to PGY-3s and above who plan to enter private practice. The rotation occurs at Charleston ENT & Allergy, a large private practice group. Plans are underway to expand the program, which will enable all residents to be exposed to private practice so they can understand the challenges and opportunities in this setting, said Robert Labadie, MD, PhD, a professor and chair of the MUSC department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Clinical rotations expose trainees to many aspects of the business of medicine, such as relative value units, staffing models, ambulatory versus hospital-based charges, and ancillary services, including in-office imaging and hearing aid dispensing, he said.

A Closer Look

The otolaryngology residency program at the University of Virginia School (UVA) of Medicine in Charlottesville, Va., includes a three-month private practice rotation for PGY-4 residents in Fredericksburg, Va., about 1.5 hours northeast of Charlottesville. The rotation gives residents a true taste of private practice otolaryngology, said Bradley Kesser, MD, a professor and vice chair in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery.

Doing small cases in an ambulatory setting versus the operating room saves money and is good for patient care without sacrificing quality. Residents learn about healthcare utilization and how to use resources in the most efficient ways. — Bradley Kesser, MD

Residents live in a house next door to the clinic while they see patients in the clinic and operate with a group of private practice otolaryngologists. “Residents learn about private practice otolaryngology, as well as how to run a medical practice,” Dr. Kesser said. They learn how to operate a small business, including experience with accounts payable, accounts receivable, coding, billing, and collecting.

“I think the experience residents get during this rotation is transformative,” Dr. Kesser said. They perform thyroid, parathyroid, endoscopic sinus, and facial plastic surgery—including rhinoplasty and soft tissue surgery of the head and neck. Residents perform 30 to 50 key indicator cases during the three-month block.

Residents also gain an understanding of the importance and value of in-office procedures. “Doing small cases in an ambulatory setting versus the operating room saves money and is good for patient care without sacrificing quality,” Dr. Kesser said. “Residents learn about healthcare utilization and how to use resources in the most efficient ways.

“Perhaps, most importantly, residents are empowered to be primary surgeons,” he continued. Residents don’t compete with co-residents for cases. They are the only resident on the Fredericksburg rotation, so they get one-on-one instruction. They learn to be the lead for an operating room, moving patients in and out. “Residents return from Fredericksburg as better surgeons and clinicians with confidence, expanded knowledge, and sharper clinical acumen and judgment.”

Dr. Kesser worked in private practice prior to joining the UVA otolaryngology department. He lectures about this experience and discusses topics such as contract negotiation, contract terms, reimbursement, the path to partnership, the experience of seeing patients, and quality of life.

Additionally, three private practitioners are on UVA’s faculty in Charlottesville. Although residents don’t rotate in the clinic or in the local hospital’s operating room with these physicians, if the practitioners have cases they wish to handle at UVA, residents join them. “In this setting, residents get excellent additional exposure to the field of otology, cochlear implants, sleep medicine, and the new technology associated with treating obstructive sleep apnea,” Dr. Kesser said.

UVA also has a graduate medical education institutional lecture series, which features financial planners giving talks about retirement planning, owning a house, insurance and disability insurance, and student loans.

Private Practitioners Reflect on Their Residencies

Although more efforts are being made to expose residents to private practice, otolaryngologists reflecting on their training said they had few discussions about handling the business of medicine or working in a private practice. Nonetheless, many pursued private practice as a result of their own motivations.

“During training, I didn’t want to choose just one area of otolaryngology,” said David Yen, MD, president of Specialty Physician Associates and chief of otolaryngology at St. Luke’s University Health Network, both in Bethlehem, Pa. “I enjoyed the breadth of the specialty and realized that I wanted to be a general otolaryngologist.”

While Dr. Yen was training in Philadelphia, an hour away from where he was raised, some patients from his hometown traveled there for care. “I realized that there must be an opportunity to return home to provide care there,” he said. Two years later, Dr. Yen joined a physician in private practice who had referred a patient to him.

Like Dr. Yen, Doug Henrich, MD, president of Burlington ENT at Southeast Iowa Regional Medical Center in Burlington, was motivated to enter private practice so he could see patients with a wide range of issues. “I wanted to work on an extensive variety of cases and fully use my training,” he said. “Our field is constantly changing and improving; private practice keeps pace with continued learning opportunities. New procedures, such as the Inspire implant, and new office technologies are available to motivated entrepreneurial otolaryngologists.”

Gene Brown, MD, RPh, president and CEO of Charleston ENT & Allergy, knew he would work in private practice before starting residency. “I was drawn to the entrepreneurial opportunities available in this setting and wanted to run a business,” he said. “As I got further along in training and some of my older colleagues graduated and started working in private practices, I got some confirmatory exposure through conversation with them.”

What’s Lacking

In general, Dr. Henrich said, residencies lack exposure to working in private practice. “A one-month private practice rotation for third- and fourth-year residents would be an excellent introduction,” he said. “This would expand their perspective, enable them to see a different practice model, and give them an opportunity to be involved in many cases and patient encounters at a fast-paced office. The business aspect of medicine is becoming more complex. Being mentored by successful private practitioners would bolster residents’ knowledge base and enhance their economic and financial skills.”

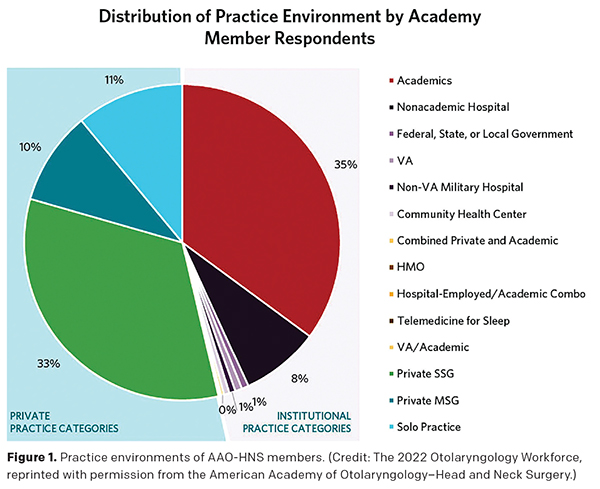

Private practice was never formally mentioned or discussed as an option during Dr. Yen’s residency. He believes that most practice opportunities remain outside of traditional academics (AAO-HNS statistics tend to agree; see Figure 1).

Private practice was never formally mentioned or discussed as an option during Dr. Yen’s residency. He believes that most practice opportunities remain outside of traditional academics (AAO-HNS statistics tend to agree; see Figure 1).

Dr. Yen thinks it’s important for future colleagues to recognize that there’s more overlap now between private practices and academics than ever before. His private practice offers a residency program and is quite active in clinical research.

“Residents need to see and understand the full range of career options during their formative years,” said Dr. Brown. Historically, general otolaryngologists have practiced in the private sector while subspecialists have practiced in tertiary care centers. This model has offered robust access for the exceptional care of more common otolaryngology problems in the community while also driving appropriate subspecialty referrals to academic centers, including exceptional care of less common diseases, he said.

Over time, however, a rapid expansion of subspecialty fellowships has occurred. “As training programs become more subspecialty centric, it shouldn’t be surprising that more trainees have pursued further specialization,” he said.

In the AAO-HNS workforce survey, 75% of chief residents indicated that they intended to pursue fellowship training. “As more graduates pursue subspecialty practice instead of general otolaryngology careers, I’m concerned that the resultant workforce imbalance may result in unintended consequences for the specialty and affect access to care in the long term for patients and communities,” Dr. Brown said. “If today’s residents had more experiences in general otolaryngology and private practice during training programs, I suspect that there would be a more balanced pursuit of general and subspecialty otolaryngology practice among trainees.”

Residents Weigh In

Many otolaryngology residents ultimately decide to work in private practice settings. But do these residents get enough exposure to this practice type during their training so they can make well-informed decisions and be prepared to work in this environment?

Roshansa Singh, MD, a resident physician in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Connecticut in Farmington, said her residency program provided just enough exposure to private practice. “We’ve had the good fortune of interacting with otolaryngology attendings that primarily staff a major, inner-city hospital while operating their private practice clinics in various locations,” she said. “We also work with another physician group that has transitioned from a multidisciplinary group to private practice. This has given great insight into the skills and capabilities required to manage a surgical subspecialty efficiently and effectively in the private practice setting.”

It would be interesting to incorporate the business and managerial aspects of private practice into our education, which residents often aren’t privy to unless they seek out these fields in their own time. — Roshansa Singh, MD

By performing select procedures in a clinic setting and working with attendings in the private sector, Dr. Singh has garnered an understanding of the necessary steps to provide high-value care to patients while ensuring they’re comfortable and relaxed.

Elizabeth Ritter, MD, a resident in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, has spent about one-third of her residency at WakeMed Hospital in Raleigh. “This offers a small glimpse into what private practice is like, particularly in regard to its outpatient clinics as well as discussions regarding their experience buying into and operating at a local surgical center,” she said. WakeMed is a hospital-based program, not a true private practice, however.

Learning more about the different aspects of operating a business would be helpful, some residents said. “It would be interesting to incorporate the business and managerial aspects of private practice into our education, which residents often aren’t privy to unless they seek out these fields in their own time,” Dr. Singh said. “I believe these skills would be valuable to all physicians, not only to those in private practice, as our field expands to incorporate third-party investors and larger conglomerates. Understanding this aspect of medicine would equip physicians to be more independent and effective in their patient care delivery.”

Dr. Ritter has learned a lot about private practice operations through job interviews over the last two years; however, she would have liked to have had a better understanding of business operations earlier in residency to help her make more informed decisions. Topics of interest include how to evaluate a contract, negotiation strategies, compensation structure (e.g., salaried vs. relative value units), practice buy-in and buy-out structures, how to evaluate a practice’s health, private equity considerations, and how to market yourself to referring providers.

Hannah Kuhar Morrin, MD, a resident physician in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Ohio State University in Columbus, is satisfied with the level of exposure to private practice during her training at a large tertiary care academic medical center. She has had the opportunity to learn about the operational and strategic aspects of private practice, including how to design and build a practice and how to operationalize short and long-term goals with a team of stakeholders.

Many residents do end up pursuing a position in private practice. Dr. Ritter accepted a private practice job mainly to have greater autonomy. “It was very important to have a seat at the table and an opportunity to help make decisions on a daily basis,” she said.

Dr. Singh is planning to join a private practice group after graduation. “My choice is partially because my mother is a happy and successful solo practitioner running a private practice company herself,” she said. “I’ve seen the autonomy, flexibility, and efficiency in private practice groups, regardless of specialty, and I’d like my career to incorporate these same characteristics.”

Dr. Kuhar Morrin would strongly consider private practice. She has a background in healthcare management, has worked at small medical clinics in rural Guatemala and Tanzania during college, and has consulted on hospital operations for a private for-profit American healthcare system. During residency, she seized opportunities to design processes to enhance resident learning and patient care through the development of a clinical and operative anatomy skills training program (a cadaver dissection course for trainees) and an enhanced recovery-after-surgery protocol for head and neck cancer patients.

“The private practice setting would allow me to readily integrate creative thinking, rapidly changing innovative technologies, and relationship-driven patient centered care into a team-based setting,” Dr. Kuhar Morrin said.

A Win-Win

Nariman Dash, MD, chief of surgery in the department of surgery at Mary Washington Healthcare in Fredericksburg, Va., and associate clinical professor in the department of otolaryngology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, who’s also the program director for UVA residents during their private practice rotation, said that having residents at his practice has made him a better clinician.

“Residents see patients before a workup has been done, which allows them to identify worrisome signs and symptoms,” Dr. Dash explained. “This differs from academic referral centers, where most patients come in with a likely diagnosis and are there for definitive care. Residents get to see their impact on the community and get quick feedback on the outcome of their treatments or surgeries. They also learn about managing a medical practice by engaging in discussions about issues that arise.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in San Diego, Calif.