© Ico Maker / shutterstock.com

If the past two decades have taught the medical world anything, it is that healthcare providers can never be too prepared for a disaster.

Although medical facilities in the U.S. are required by state regulators and accreditors to create emergency preparedness plans, such plans don’t always anticipate the ultimate impact of a crisis, be it environmental or man-made. The potential short- and long-term effects of a powerful hurricane, tornado, or earthquake differ vastly from those of a widespread power outage, mass shooting, or viral pandemic. Yet, healthcare organizations must be agile enough to respond to all of these.

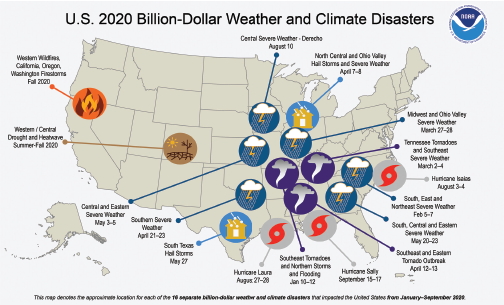

As emergency preparedness experts become more adept at predicting the occurrence and effects of disasters, climate-related events are upping the ante. A 2014 National Climate Assessment issued by the U.S. Global Change Research Program reports a steady increase in the intensity, frequency, and duration of hurricanes in the North Atlantic U.S. since the 1980s, and a 2020 study found that the likelihood of a hurricane becoming Category 3 or higher rose over a 40-year span by approximately 8% per decade (see “Billion-Dollar Disasters” below). The number of tornado clusters capable of wreaking widespread destruction is also on the rise.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has created an ongoing state of emergency that impacts all health providers, but otolaryngologists in particular. This was especially true in the early months of the outbreak, when so little was known about the virus’ transmission. “There was a report out of Wuhan made available by a group of ENT doctors at Stanford University that documented a sentinel surgical case in which a surgical team performed endoscopic transnasal surgery on a COVID-positive patient,” recalled Daniel W. Nuss, MD, George D. Lyons Professor and chairman of the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the Louisiana State University (LSU) School of Medicine, New Orleans. “There were 14 support people in the operating room, including the surgeons, and all of them got sick with COVID. Subsequently, in Asia, Iran, and Italy, some of the highest mortality rates from COVID were among ENT doctors. So, this was almost a panic point for otolaryngologists.”

For doctors, nurses, and other medical personnel on the front lines of disaster, every experience brings hard-won lessons on what it means to serve a community under siege, and what lessons can be gained in the aftermath.

The Legacy of Katrina

On Aug. 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Louisiana Gulf Coast, bringing with it 127 mph winds and subsequent flooding that lasted for weeks. When it was over, more than 1,800 people had died in and around the state, and the cost of damage totaled an estimated $161 billion. By far, the city of New Orleans, which sits predominately below sea level, was the hardest hit.

Evelyn Kluka, MD, was both an associate professor at the LSU School of Medicine and director of pediatric otolaryngology at Children’s Hospital in New Orleans when reports of Katrina’s projected path were issued. In response, the hospital called a Code Grey. “The procedure includes discharging medically stable patients and determining the team of physicians considered essential personnel,” Dr. Kluka said. “Employees—nurses, pharmacists, assistants, and respiratory therapists, among others—are divided into teams and assigned shifts.” Following the advice of the hospital’s CEO to “get your personal affairs in order or you won’t be good for anyone else,” Dr. Kluka and her family evacuated to higher ground.

As Dr. Nuss explained, although nature had dealt the storm, man-made problems severely worsened its aftermath. “In New Orleans, parts of which are below sea level, there’s a delicate balance of man-made structures that help pump water out when it builds up. When that system is overwhelmed, we’re essentially a swamp,” he said. “In Katrina, there was a sequence of really bad management of the levee systems of the Mississippi River, the public works, and the Army Corps of Engineers that compounded everything. Ultimately, there were bodies floating in 10 to 12 feet of water, which covered our city for weeks. We had muck, mold, and decaying vegetation that had nowhere to go, and a surreal absence of birds and other wildlife.”

Although the staff at Children’s Hospital was still relying on its emergency generators, “the loss of the city’s water supply affected its ability to run the physical plant,” said Dr. Kluka. For the first time in 50 years, the hospital closed its doors. Dr. Kluka, with no place to practice or patient charts to reference, began to advise her patients to seek care in the communities to which they had scattered.

Our hurricane preparedness helped serve as a blueprint for dealing with the onset of COVID. We now have a robust supply chain, and our resources are spread across the system. —John Carter, MD

With New Orleans hospitals wiped out, and half of LSU’s residents and even more of its faculty gone from the area, the facility’s otolaryngologists offered their services in neighboring cities that weren’t as severely affected, such as Baton Rouge and Lafayette. “We were warmly welcomed [by other cities in the regions that were less affected] to bring our patients, residents, and students, which enabled us to resume normal business and start rebuilding the elements of an academic program,” said Dr. Nuss, who now gives talks to physician groups about emergency preparedness. As for LSU’s displaced residents, the broader otolaryngological community stepped up with offers to continue their programs at places such as MD Anderson, the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of North Carolina.

Rebuilding from Katrina has led to changes that have yielded lasting benefits. “Interestingly, one of the earliest innovations was by necessity—we got into telemedicine to a much greater extent than we had before,” said Dr. Nuss. “Faculty members who traveled to points far and wide were still able to furnish consultations. We learned then what many people are learning today from the COVID-19 experience: Telemedicine is a convenient and very useful tool for assessment and giving therapeutic advice. It can be a wonderful tool for triage as well.”

Adapting Past to Present and Future

The particulars may vary, but each disaster leaves an indelible imprint and lessons that become part of daily life. “The disaster experience creates an institutional memory that persists permanently,” said Jason Y.K. Chan, MD, MBBS, director of undergraduate teaching and an associate professor in the department of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Dr. Chan cited the 2003 SARS infection as a game changer for the facility. “Since then, we have continued to wear masks and gowns in clinics,” he said. “Everyone is fit-tested for N95 masks on starting a job in a public hospital. There’s always a good stock of PPE available.”

The protocols put in place at The Chinese University of Hong Kong to address COVID-19 reflect a grim sense of reality regarding the management of infectious disease. “We’ve just had our third wave, so our operations stop and start,” said Dr. Chan. “Elective operations have been cut during waves, and there’s a longstanding effect as we work to clear a backlog of patients who need to be seen again.” He foresees no change to this status for “the next one to two years at a minimum.”

“Our hurricane preparedness helped serve as a blueprint for dealing with the onset of COVID,” said John Carter, MD, section head of pediatric otolaryngology–head and neck surgery for Louisiana-based Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. “We now have a robust supply chain, and our resources are spread across the system. For COVID, we were able to shift patient admissions to facilities with more capacity and move physicians, nurses, and medical assistants as needed to handle the surge. I was blown away to work with people from all different specialties who were there to help. The response from our team was incredible. The resiliency we gained from our experiences makes it easier to pick up the pieces and rebuild.”

Rohan R. Walvekar, MD, clinical professional and director of the Salivary Endoscopy Service and co-director of the ENT Service at the University Medical Center in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at LSU, participated in the post-Katrina rebuilding led by Dr. Nuss. “What I see as most relevant in dealing with the aftermath of a disaster—and which also set the stage for facing other challenges, including COVID-19—was to find the true strength of a collective team and mind,” he said. “Given the challenges we faced as a department in the past, when the COVID pandemic became apparent and New Orleans was one of the hot spots, we rallied together. We took stock of the situation, held working group sessions to prioritize and triage efforts related to patient and surgical care, and connected regularly to share information and harness resources to keep our residents, staff, and faculty safe.”

Consensus among disaster-experienced otolaryngologists is that information sharing is paramount. “The most important piece in my eyes is constant communication with our people and a clear, concrete plan for each clinic and hospital site across the system. This reduces confusion and anxiety,” said Dr. Carter. “That being said, we’ve learned from storms like Katrina and with COVID-19 that communication is often fluid; you have to be malleable and understanding enough to deal with a rapidly changing situation.”

Dr. Walvekar agreed. “One of the major challenges is being able to sift through the quantity of new and constantly emerging data on the nature of a healthcare entity that there was so little information on,” he said. “One of the ways we managed this was by diligently following state health recommendations, putting our patients’ and team members’ safety first, and preparing adequately for situations where we had to be on the front lines. We created task forces to help with decision making. For example, we created a committee for surgical optimization and resource utilization to help triage elective surgeries and maintain a database of decisions made so we could learn from them.”

The advancement of technology in recent years has been instrumental in this effort, said Dr. Kluka. In 2012, she moved from Louisiana to a beach community in Florida, where she’s division chief of otolaryngology at Nemours Children’s Specialty Care in Pensacola. Recently, Hurricane Sally brought strong winds, heavy rainfall, and a tidal surge to the area. Despite the resulting hardships, the experience was different. “Between 2005 and 2020, technology has improved dramatically,” she said. “With Sally, clinics and hospitals communicated announcements with employees readily, texts and emails were uninterrupted, and most of us were able to check with colleagues and associates regarding safety and resource needs.”

Online resources have also proven indispensable. “The transfer of knowledge has been greatly facilitated by social media, publications, and webinars, allowing for great discussion and quick responses,” said Dr. Chan. The online COVID-19 ENT resource library created by LSU to expand information sharing is an example of one such resource.

Reframing “Normal”

Post-disaster, it’s natural to long for a return to normal. “Normal” is relative, however, particularly in the context of an ongoing emergency like COVID-19, said Dr. Walvekar. “We can gauge progress by focusing on how we are meeting the basic goals of our academic practice in patient care, resident training, and medical student education,” he suggested. “Progress toward normal is also affected by available hospital resources and the fact that we must ration those resources carefully—for example, limited operative time. Consequently, in these challenging times, we have to manage our expectations and those of our patients by helping them understand the limitations and challenges we face as a medical community.”

What I see as most relevant in dealing with the aftermath of a disaster—and which also set the stage for facing other challenges, including COVID-19—was to find the true strength of a collective team and mind. —Rohan R. Walvekar, MD

Returning to normal happens in stages, said Dr. Carter. “You first have to define a safe environment in which to bring back workers and patients. During Katrina, this was when the water was clear and the utilities had returned. During COVID, it was when we had the safety protocols in place to keep patients and staff safe and compliant with department of health rules.”

Disasters tend to bring irreversible changes that challenge the very idea of normalcy. Some changes are immediate and apparent. “The challenges following a hurricane can include closed schools and, therefore, unexpected childcare issues,” said Dr. Kluka. “There are fallen trees, continuing flood water, damage to property, loss of electricity and drinkable water, and possibly missing or lost loved ones. Traffic issues increase with loss of usable roads, and there’s an influx of workers and insurance adjusters.”

Other changes are less obvious, although they can be just as damaging, if not more so. Dr. Nuss remembered the psychologically destabilizing aspects of life in New Orleans post-Katrina. “All the things that used to be familiar to you are no longer familiar at all, and you have to piece together in your own mind what things used to look like to orient yourself,” he said. “Just the stench, which lasted for weeks and weeks, was one of the most difficult parts of reestablishing a connection with the city.”

During a public health emergency, physicians and other medical personnel may be called to work under intolerable circumstances. “After Katrina, there was no getting in or out of hospitals, so there were employees who were forced to be on duty continuously, and yet, without resources, could only stand by while people suffered. There was no running water or air conditioning—and this was September, which is always one of the hottest months here, with 100% humidity and no open-window ventilation,” said Dr. Nuss. “I know a lot of people who had to get professional counseling to deal with the helplessness and misery that followed in the immediate wake. It was a little bit like wartime. There was a lot of long-lasting psychological damage.”

The real things people need after a disaster often involve physical work or base-level first aid. It was amazing after Katrina how many super-subspecialists signed up to do time in neighborhood clinics, just to help where they could. —Daniel W. Nuss, MD

In the rush to rebuild vital structures and systems, the need to address a disaster’s impact on staff morale and emotional well-being might be overlooked. After Katrina, Ochsner Health provided emotional support resources and daycare for children, and also “made sure that people got their hours,” said Dr. Carter. “You focus on the people first, and the other stuff falls in line.”

Billion-Dollar Disasters

Although we’re better at predicting disasters, climate-related events are growing. A trend analysis shows that, as of July 8, 2020 is the sixth consecutive year in which 10 or more weather and climate disasters in the U.S. have caused losses in excess of $1 billion.

Source: National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,

https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/

Health providers may be especially susceptible to disaster-related psychological stress. “The effects of isolation and inability to work at capacity can be extremely challenging, especially for a group of people who are used to being highly efficient and busy,” said Dr. Walvekar. “The best way to address these issues is to recognize them and face them together. During the worst months of the COVID crisis here, our group met regularly to discuss clinical, individual, and group challenges. Under the right leadership, a disaster experience can help rally faculty and residents to a common goal and vision, which is vital to staying positive and focused.”

Surviving a disaster is a humbling experience for anyone, regardless of their professional status. “No matter what you do for a living, the real things people need after a disaster often involve physical work or base-level first aid,” said Dr. Nuss, who is an otolaryngologist, a skull base surgeon, and a surgical oncologist. “These aren’t glamorous things in medicine, but they need to be done. It was amazing after Katrina how many super-subspecialists signed up to do time in neighborhood clinics, just to help where they could. It reinforces why we should be generous with our time and talents when people are in need, and even as specialists, we should always stay current on the basics of general medicine. That’s one of the lessons.”

Linda Kossoff is a medical freelance writer in Woodland Hills, Calif.

Business Continuity Plans

According to disaster experts, having a plan in place to get your business through the first 72 hours after a disaster occurs is vital. If you have your own practice, consider these steps in creating your own plan.

Create Multiple Scenarios. A single plan won’t adequately address every type of disaster. As you plan, consider as many factors as possible that could disrupt your business, and perform a risk assessment that includes actions to mitigate or respond to those risks and details how you’ll communicate with staff and patients.

Identify Essential Personnel and Supplies. Establish a preparedness team and assign duties to each member. Have back-ups in place in case some team members aren’t available. Identify the essential daily functions of your practice, and the minimum that must be done to keep patients safe and your practice up and running. Supply shortages are a concern for many types of disasters. You may need to be prepared to pay additional shipping charges for critical materials, or overstock your business in preparation.

Test Your Plan Often. Having a business continuity plan in place means nothing if you and your staff haven’t run through scenarios to ensure that nothing is missed.