The use of a frailty index (FI) that takes more into consideration than chronologic age is gaining momentum as a tool for assessing whether patients can stand the rigors of surgery for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and other potentially risky head-and-neck procedures.

In the case of surgery for OSA, although the risk for serious adverse events is often cited as less than 2% (Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450-453), that rate “soars” in the presence of multiple comorbidities, said Robert Stachler, MD, division head of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Lakeside Medical Center (Henry Ford Health System) in Detroit, who has helped develop an FI for head and neck surgeries based on several existing risk assessment tools.

“The problem is, if you just rely on a patient’s age and don’t account for physiologic age, you may miss the comorbidities that can tip the scales toward not performing surgery, even in relatively young patients,” Dr. Stachler said. “Conversely, we sometimes wrongly assume that patients in their 70s and 80s are ‘too old’ to undergo these procedures, and in such cases we may be depriving them of an effective therapeutic intervention.”

At the Triological Society’s annual meeting at the Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings, held in May in Las Vegas, Dr. Stachler presented a study he co-authored that detailed just how effective his team’s FI can be in predicting which otolaryngology patients will develop severe morbidity and mortality as a result of surgery for OSA and other conditions (JAMA Otol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:783-789). The study—the first ever to assess an FI in otorhinologic surgery—was based on data from nearly 7,000 patients (mean age, 54.7 [16-90] years) culled from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), “which is about as robust and reliable a database as you can find when it comes to tracking the risks versus benefits of surgery,” Dr. Stachler said.

The FI assessed in the study drew heavily on a comprehensive geriatric assessment known as the Canadian Study of Health and Aging-Frailty Index (CSHA-FI). “[This] index includes 70 variables that measure important deficits, including poor cognition, physical ailments, social problems, etc.,” Dr. Stachler said. “But it was way too broad for use in our head and neck patients. So we had some winnowing to do.”

Using the NSQIP data set as a partial guide, the investigators reduced those 70 items to 11 variables that were contributing to poor outcomes. The shortened list included history of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease, among others. “A previous study by Rockwood and colleagues (BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24-33) showed that even a list of 10 items from the CSHA-FI index can reliably predict poor surgical outcomes, so we knew we were on the right track,” Dr. Stachler said.

Physicians are way too accustomed to thinking of age as an important predictor of complications when, in fact, frailty is likely the strongest predictor.

Physicians are way too accustomed to thinking of age as an important predictor of complications when, in fact, frailty is likely the strongest predictor.—Robert Stachler, MD

The next step was to use the resultant “modified” frailty index (mFI) to calculate a score for each patient in the study. The researchers made those calculations by dividing the number of comorbid conditions and other variables deemed to be present in a given patient by the total number (11) of variables assessed by the investigators. They then determined whether the mFI scores correlated with post-surgical outcomes.

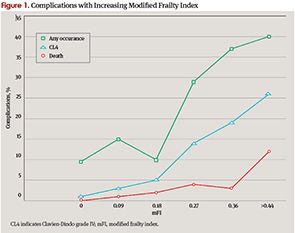

“What we found was, frankly, astounding,” Dr. Stachler said. “As the mFI score reached 0.45 or higher—that is, approximately 5 of 11 variables present—mortality increased from 0.2% to 11.9%.” Moreover, the risk for grade IV complications, such as post-operative septic shock, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism, increased from 1.2% to 26.2%, he reported. The risk of all complications increased from 9.5% to 40.5% (P<0.001).

“The frailty index proved to be a very powerful predictive tool,” Dr. Stachler said. “In fact, it did a far better job at predicting morbidity and mortality than the historical variables we all tend to rely on—wound class, physical status, and age.”

The overreliance of some physicians and surgeons on age is something that Dr. Stachler said couldn’t be overstressed as a pitfall. “As we made clear in our paper, physicians are way too accustomed to thinking of age as an important predictor of complications when, in fact, frailty is likely the strongest predictor.”

Poised for Prime Time?

Dr. Stachler’s presentation was part of a Triological Society annual meeting session that explored “Issues You Cannot Ignore in Older Patients.” The reaction he got from attendees was that this FI data certainly should not be ignored, he said.

But should it be put into clinical practice? “To some degree, yes, but it does need some further tweaking and validation,” Dr. Stachler said. Once that is done, he noted, a next step might be to develop algorithms that surgeons can use to individualize therapy based on a patient’s unique mFI score. If, for example, a patient’s score indicates a higher risk for post-operative stroke or heart attack, “even before that patient reaches the OR, our team can use the algorithms to develop individualized post-operative care for those patients,” Dr. Stachler said. Such a strategy, he said, can’t help but make better physicians and surgeons for otolaryngology patients.

That scenario is very appealing to Jonas T. Johnson, MD, Dr. Eugene N. Myers Professor and Chairman of the department of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Dr. Johnson said that he and his colleagues “are on track in helping all surgeons better understand techniques we might employ to enhance personalized medicine.” He added that he was introducing a study at the University of Pittsburgh to see if they can corroborate Dr. Stachler’s results.

If validated, Dr. Johnson said, such a tool could help address an important challenge in geriatric medicine: how to limit surgery and other interventions to patients who can truly benefit. “The majority of healthcare dollars are spent on terminal illness,” he said. “Also, 75% of people have surgery in the last year of their lives, and, when polled, most Americans respond that they would refuse surgery under this circumstance. Of course, physicians are in the business of trying to help. But is it possible that, in our efforts, we are actually hurting some people, or perhaps subjecting them to interventions that are doomed to fail?”

He added that frailty “is one of those terms that we all understand, but no one can precisely define. Surgeons understand this problem and would certainly benefit from improved metrics to help us understand how to better assist our patients”.

Michael Setzen MD, clinical associate professor of otolaryngology at NYU School of Medicine in New York City and past chair of the board of governors of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, offered a more tempered assessment. “I personally do not use this [type of] index when considering the elderly for surgery,” said Dr. Setzen. “I also don’t believe it is used much by others elsewhere in the United States,” so its clinical utility remains to be determined, he told ENTtoday.

A Proven Strategy

Dr. Stachler stressed that his team’s efforts to develop a frailty index are not happening in a vacuum; during his Triological Society annual meeting presentation, he briefly reviewed efforts by several other investigators who are using similar tools for assessing pre-operative risk in broader patient populations. And some of their results are equally striking. In one study of colorectal cancer patients, a comprehensive geriatric risk assessment tool showed that frail patients had at least a two-fold higher risk of developing severe post-operative complications when compared with fit patients (33% versus 62%; P=0.002) (Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76:208-217); moreover, in findings similar to those of Dr. Stachler, the authors reported that increasing age and functional status “were not associated with complications.”

In Dr. Stachler’s view, a lot of this is just common sense, albeit confirmed with “a very new, fresh, and exciting” model of risk. “I sometimes see this in my practice, and you certainly hear it all the time: You have an 85-year-old patient who just doesn’t look their age. They still drive a car, they exercise, and their cognition is spot-on. And, because they’ve taken great care of themselves, they don’t have any of the comorbid variables our frailty index weighs so heavily, such as diabetes, hypertension, etc. So biologically, they may be nearer to 60 years of age. Are you really going to deprive them of a surgery that can increase their quality of life even more?”

Armed with a frailty index to assess patients pre-operatively, “such questions won’t even have to come up,” Dr. Stachler said. “It’s a tool that hopefully will remind us of what we should really be looking at in our older patients.”

Leave a Reply